1 Theory-based Debriefing Methods

Debriefing is a cornerstone of healthcare simulation education, playing a critical role in enhancing learning outcomes and ensuring that students can reflect on their experiences to improve future practice. In recent years, the use of evidence-based debriefing has gained prominence, as research shows that structured debriefing sessions significantly enhance the transfer of skills and knowledge to real-world clinical settings (Fey & Jenkins, 2015). The process of debriefing involves guided reflection on a simulation scenario, encouraging learners to think critically about their decisions, actions, and their consequences. The aim is not just to assess performance, but to foster deep learning through structured, theory-based approaches to feedback and reflection.

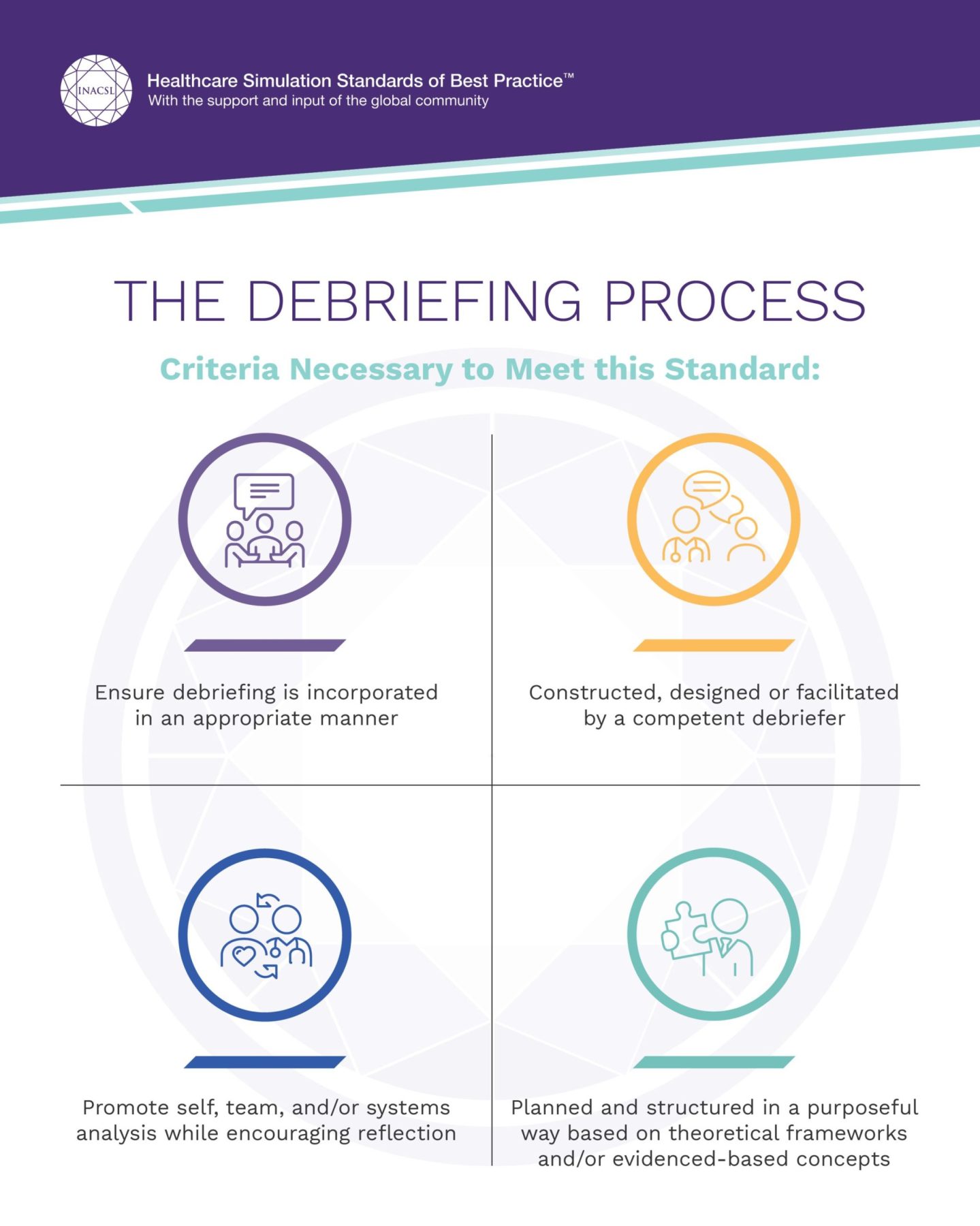

This chapter introduces the theory, standards, and methods that underpin effective debriefing in healthcare simulations. It also explores the Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: Debriefing, developed by the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL), which provides a framework for facilitating meaningful, evidence-based debriefing (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021). These standards emphasize the importance of using structured models, such as the Debriefing for Meaningful Learning (DML) framework, to guide reflective practice and ensure consistent outcomes across various learning environments (Dreifuerst, 2012).

Learning Objectives

- Describe the theoretical underpinnings of debriefing, along with the standards and methods that support reflective practice in simulation.

- Facilitate debriefing using theory-based methods to ensure that learners are engaged in meaningful reflection and knowledge integration.

- Evaluate debriefing sessions—both self and peer evaluations—using valid and reliable tools to ensure they meet established educational outcomes.

Through these objectives, this chapter aims to equip nursing and healthcare educators with the knowledge and tools needed to conduct effective debriefing, grounded in evidence-based best practices. It also highlights the importance of debriefing as a dynamic process that not only assesses student performance but also cultivates a deeper understanding of clinical practice.

I. The Debriefing Process in Healthcare Simulations

Debriefing is an integral part of simulation-based learning in healthcare education, serving as a structured reflective process where students analyze their performance in a simulation scenario. This process allows learners to critically assess their clinical decision-making, actions, and the outcomes, enhancing both cognitive and emotional learning (Dreifuerst, 2012). The primary goal of debriefing is not only to identify what went well or what could be improved but also to foster critical thinking and knowledge retention through guided reflection and feedback.

- Stages/Phases of Debriefing

The debriefing process typically follows three stages:

Reaction Phase: In this initial stage, participants are encouraged to express their immediate emotional responses to the simulation experience. This allows learners to release any anxiety or tension, which can then facilitate more objective reflection on the events of the scenario (Fey & Jenkins, 2015).

Analysis Phase: This is the core of the debriefing process, where students and facilitators discuss key events of the simulation. During this phase, the instructor asks open-ended questions to encourage reflection, critical thinking, and deeper understanding. Various models, such as the Debriefing for Meaningful Learning (DML) or the GAS model (Gather, Analyze, Summarize), and Debriefing with Good Judgment, among others,are used to structure these discussions. The aim is for students to explore why certain actions were taken, the clinical reasoning behind those decisions, and alternative approaches that might have yielded better outcomes (Dreifuerst, 2012).

.Summary Phase: In this final stage, key lessons from the simulation are highlighted, and the instructor helps consolidate the knowledge gained. The summary phase reinforces learning by connecting the experiences in the simulation to clinical practice, ensuring students leave with actionable insights for future performance (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

- Key Components of Effective Debriefing

•Facilitator-Guided Reflection: A trained facilitator plays a crucial role in guiding the debriefing process. The facilitator asks probing questions, provides constructive feedback, and ensures that discussions remain focused on the learning objectives.

•Structured Frameworks: Using evidence-based models for debriefing, such as DML, helps maintain consistency and ensures that the reflection is meaningful and comprehensive. These frameworks emphasize critical analysis and support cognitive, emotional, and social learning.

•Psychological Safety: Creating a safe, non-judgmental environment is essential for effective debriefing. Learners must feel comfortable discussing their mistakes and exploring their decision-making without fear of criticism. Psychological safety fosters openness and promotes deeper learning.

•Feedback and Evaluation: In addition to reflection, debriefing provides an opportunity for feedback. Peer and self-evaluation are often encouraged, and facilitators use this feedback to assess how well the debriefing met its educational goals (Fey & Jenkins, 2015).

- Benefits of Debriefing

The debriefing process enhances the overall effectiveness of simulation-based education by turning simulation experiences into learning opportunities. It helps students develop clinical reasoning, improve communication and teamwork, and fosters reflective practice, all of which are crucial in real-world healthcare settings. Through structured debriefing, learners can better understand their strengths and areas for improvement, ultimately improving their competence and confidence in clinical practice.

II. The International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulations and Learning (INACSL) Healthcare Simulations Standards of Best Practice (HSSOBP)

Adhering to the INACSL Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: Debriefing is essential because these standards provide a structured, evidence-based approach to enhancing the quality of debriefing sessions in simulation-based education. Debriefing is a critical part of the learning process in healthcare simulations, where students reflect on their actions, receive feedback, and make connections between simulation scenarios and real-world clinical practice. Without following established guidelines, the debriefing process risks becoming inconsistent and less effective in fostering deep learning and skill acquisition (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

The INACSL standards emphasize psychological safety, ensuring that learners feel comfortable discussing their mistakes without fear of judgment. This environment is crucial for promoting open dialogue and deeper critical reflection, which is often where the most meaningful learning occurs (Fey & Jenkins, 2015). The standards also encourage the use of structured debriefing frameworks, such as the Debriefing for Meaningful Learning (DML) model, to guide facilitators in delivering focused and purposeful feedback. Evidence has shown that structured debriefing improves learning outcomes, helping students better understand clinical reasoning and decision-making processes (Dreifuerst, 2012).

Additionally, the standards call for the use of valid and reliable evaluation tools to assess the effectiveness of debriefing. This promotes consistency in debriefing practices and ensures that the sessions align with educational objectives, ultimately improving the quality of healthcare education (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

By following the INACSL debriefing standards, nursing and healthcare educators ensure that debriefing sessions are conducted with the highest level of rigor, resulting in better-prepared graduates who are equipped with the skills, critical thinking, and confidence needed in clinical practice.

Nurse educators who debrief clinical simulations must be guided by standards. Read the full length article:

Knowledge check

III. Theoretical Foundations of Debriefing

Debriefing is a critical educational strategy within clinical simulation that serves as a bridge between theoretical knowledge and practical application. The theoretical foundations of debriefing are rooted in several key learning theories that emphasize reflection, experiential learning, and transformative education. By grounding debriefing in these theoretical foundations, educators can ensure that the debriefing process goes beyond a simple review of actions and fosters deeper cognitive processing, leading to better learning outcomes and preparedness for real-world clinical settings.

A. One of the most influential frameworks guiding debriefing practices is Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (1984), which posits that learning occurs through the cycle of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. In simulation-based education, debriefing functions as the reflective observation phase, where learners critically examine their actions and decisions in the simulation to better understand the outcomes and refine their clinical reasoning.

Watch and Learn

Reflect: How can nurse educators use Kolb’s theory to support simulations and debriefing? In the classroom? In clinical education?

B. Vygotsky’s Social Constructivism also plays a pivotal role in the theoretical foundation of debriefing. His concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) suggests that learning is maximized when individuals engage in tasks slightly beyond their current abilities with the guidance of a more knowledgeable other, such as a facilitator (Vygotsky, 1978). In debriefing sessions, the facilitator leads learners through reflective conversations, helping them identify gaps in their knowledge and guiding them to better understand their clinical decision-making processes.

As you watch the video below, answer the following questions:

- What is your role as the clinical expert when debriefing simulations?

- How do you use the concepts of this theory in developing nursing students clinical knowledge?

- What language strategies will you use when debriefing?

C. Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory (1978) provides a powerful framework for reflection and personal transformation, both of which are essential components in debriefing after clinical simulations. This theory posits that transformative learning occurs when individuals critically reflect on their assumptions, beliefs, and actions, leading to a shift in their perspectives. In the context of clinical simulation debriefing, Mezirow’s theory supports a process where learners not only evaluate their clinical performance but also engage in deeper reflection that challenges their preconceived notions and fosters professional growth.

Mezirow identified critical reflection as the heart of transformative learning, emphasizing that learners must engage in reflective discourse to question and evaluate their beliefs, assumptions, and values. In a debriefing session, the facilitator helps guide this process by prompting learners to analyze why they acted in certain ways during the simulation and to consider alternative approaches. This reflection is crucial for helping students recognize any gaps in their clinical reasoning or biases in their decision-making (Mezirow, 1991). By critically evaluating their actions in the safe, supportive environment of a debriefing session, students can undergo transformative learning that influences future clinical practice.

Another key aspect of Mezirow’s theory is the concept of a disorienting dilemma, a situation that challenges learners’ existing viewpoints and triggers a reassessment of their beliefs. In clinical simulations, students often encounter complex, high-pressure situations that may lead to mistakes or decisions they later question. These moments serve as disorienting dilemmas that push learners out of their comfort zones and prompt reflection. Through guided debriefing, students can confront these dilemmas, reflect on their clinical performance, and transform their perspectives, ultimately leading to improved critical thinking and clinical competence (Mezirow, 1997).

Furthermore, Mezirow emphasizes the importance of dialogue in the transformation process. In debriefing, the open, reflective dialogue facilitated by the instructor encourages students to explore different perspectives, learn from their peers, and integrate new insights into their clinical practice. This process helps students not only learn from their own experiences but also grow through shared reflection, making the transformation both individual and collective.

In summary, Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory supports the use of debriefing in clinical simulations by promoting critical reflection, challenging assumptions, and fostering transformative growth. By guiding learners through a reflective process that encourages them to question their actions and assumptions, debriefing helps transform novice learners into competent, reflective practitioners who are better equipped to navigate the complexities of real-world healthcare settings.

As you watch the video below, reflect on the following questions:

- When do we need to transform the frames or thinking of our learners?

- What are the different frames of our learners?

- How do we transform the frames of thinking of our learners?

D. Donald Schön’s Reflective Practice Theory emphasizes the importance of reflection as a tool for learning and professional development, which directly underpins the debriefing process in clinical simulations. Schön (1983) introduced the concept of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, which have become essential frameworks in simulation debriefing. In clinical simulations, these reflective practices help learners process their actions and decisions in a structured, meaningful way, improving their clinical reasoning and future practice.

1.Reflection-in-Action:

During a clinical simulation, learners often engage in reflection-in-action, meaning they think on their feet and adjust their actions based on the immediate demands of the scenario. However, in the heat of the moment, learners may not fully understand the consequences of their decisions or the reasoning behind their actions. Debriefing provides the opportunity to revisit these decisions, exploring the rationale behind them and examining how alternative actions might have led to different outcomes. This reflection allows learners to connect their experiences to broader clinical principles, enhancing both their situational awareness and their ability to think critically in real-time (Schön, 1983).

2.Reflection-on-Action:

After the simulation concludes, reflection-on-action occurs. This is where Schön’s theory becomes central to the debriefing process. Facilitators guide learners through a detailed review of the simulation, encouraging them to reflect on their decisions and actions retrospectively. By reflecting on their performance, learners are able to identify mistakes, gaps in knowledge, or areas for improvement, while also reinforcing successful strategies. This reflective practice promotes deeper learning by transforming a clinical experience into an opportunity for growth and knowledge consolidation (Schön, 1987).

3.Facilitator-Guided Reflection:

Schön’s model also highlights the importance of facilitator-guided reflection in helping learners connect their experiences to theoretical frameworks. During debriefing, facilitators ask probing questions to help learners critically analyze their actions and decision-making processes, fostering greater self-awareness and professional growth. By reflecting in a structured environment, learners can better understand how their actions in the simulation translate to real-life clinical settings (Schön, 1983).

4.Professional Growth and Continuous Learning:

Schön’s theory supports the idea that reflection is essential for professional growth and continuous learning. In clinical simulation debriefing, reflection is not just about reviewing a particular event but about fostering a mindset of lifelong learning. Through repeated cycles of action and reflection, learners develop the ability to adapt to new situations, think critically under pressure, and continuously improve their practice. This aligns with the goals of debriefing, which seeks to ensure that healthcare professionals are not only technically proficient but also reflective, adaptive, and capable of self-assessment.

In summary, Schön’s Reflective Practice Theory forms the foundation of the debriefing process in clinical simulations by emphasizing the need for structured reflection, both during and after clinical encounters. This reflective practice helps learners critically analyze their performance, connect theory to practice, and develop the skills necessary for continuous improvement in their professional lives.

Reflective Practice: As you watch the video below, ask yourself: How do we facilitate our future nurses’ reflective practice through debriefing? Why is reflective practice important?

Knowledge check

IV. Theory and Evidence-based Debriefing Models/Methods

Several evidence- and theory-based debriefing methods are currently used in clinical simulations to ensure effective learning. These debriefing models are grounded in educational theories and supported by research, making them essential in fostering critical thinking and professional growth. Below is a list of the most commonly used debriefing methods:

1. Debriefing for Meaningful Learning (DML)

Debriefing for Meaningful Learning (DML) is a structured, evidence-based debriefing method that focuses on promoting reflective thinking, critical analysis, and the development of clinical reasoning skills in learners. Created by Kristina Dreifuerst in 2012, DML is grounded in Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory and Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory, which emphasize the role of reflection in transforming experiences into deeper learning. DML is particularly designed to facilitate the transition from novice to competent clinical decision-makers, making it a powerful tool in healthcare education, particularly in nursing simulations. DML was the debriefing method that was used in the 2014 National Simulation Study by the National Council os State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN).

Key Features of DML

- Structured Reflection:

The core of DML is its structured approach to reflection. It follows a guided process where learners reflect on the simulation scenario, discuss their thought processes, and identify gaps in their clinical reasoning. The facilitator leads this reflection by posing open-ended questions, encouraging learners to think critically about their actions and decisions, and linking them to broader clinical concepts.

- .Facilitator-Guided Debriefing:

The role of the facilitator is essential in DML. Facilitators are trained to ask probing questions that challenge learners’ assumptions, guide their analysis, and encourage them to consider alternative approaches. This active engagement with learners helps deepen understanding and supports the development of critical thinking and decision-making skills (Dreifuerst, 2012).

- Promoting Clinical Reasoning:

DML is specifically designed to enhance clinical reasoning. Through the structured reflection process, students examine their decision-making process during the simulation, helping them to identify and correct errors, consider the consequences of their actions, and improve their ability to apply theoretical knowledge to clinical situations. This reflective process is vital for preparing students for real-world clinical practice, where clinical reasoning is critical for patient safety and effective care delivery.

- .Integration of Theoretical Concepts:

Unlike other debriefing models that may focus primarily on technical skills, DML connects learners’ experiences during the simulation to theoretical knowledge. This helps learners understand not only how to perform specific tasks but also why they are performed in a certain way. The goal is to facilitate deeper learning that transcends procedural knowledge, encouraging students to apply clinical reasoning and decision-making principles in varied contexts.

- .Fostering Transformative Learning:

Rooted in Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory, DML aims to foster transformative learning by helping learners critically reflect on their experiences, challenge their assumptions, and shift their perspectives. This process of questioning and reflection helps learners develop a more complex and nuanced understanding of clinical practice, promoting long-term personal and professional growth (Mezirow, 1991).

- Evidence of Effectiveness:

Studies have shown that Debriefing for Meaningful Learning significantly improves learners’ clinical reasoning skills, critical thinking, and ability to apply theoretical knowledge to practice (Dreifuerst, 2015). Research also indicates that students who engage in DML-based debriefing are better equipped to recognize their mistakes, learn from them, and improve their future performance in clinical settings (Fey & Jenkins, 2015).

- Advantages of DML:

•Focus on Deep Learning: DML goes beyond surface-level procedural knowledge by encouraging students to engage in deep, reflective thinking.

•Structured Approach: The structured nature of DML ensures that debriefing sessions are focused and effective, with clear learning objectives.

•Enhances Clinical Competence: By improving clinical reasoning and decision-making, DML helps prepare students for the complexities of real-world healthcare.

Learning to use DML: Key Resources

Watch a clinical scenario and its subsequent debriefing using DML

2. Advocacy-Inquiry Model

Debriefing with Good Judgment, a model developed by Rudolph and colleagues, is an example of the Advocacy-Inquiry method, which integrates both facilitation and learner reflection to promote deep learning in clinical simulations. This model is grounded in the belief that debriefing should not simply be a critique of learner performance but an opportunity to understand the thought processes behind actions, using a non-judgmental yet direct approach to reflection and feedback.

Key Features of Debriefing with Good Judgment

- Advocacy-Inquiry Framework:

Advocacy: In this part of the debriefing, the facilitator clearly states an observation or expresses a concern about what happened during the simulation. The goal is to present facts or the facilitator’s view in a non-threatening, supportive manner. Advocacy helps establish common ground between the facilitator and learner, ensuring that both are on the same page about what occurred during the scenario.

Inquiry: Following the advocacy statement, the facilitator asks open-ended questions aimed at exploring the learner’s thought process. This inquiry is crucial as it invites the learner to reflect on the reasons behind their actions, leading to greater self-awareness and critical thinking. It also encourages deeper discussions that reveal underlying assumptions or knowledge gaps.

Together, advocacy and inquiry provide the structure to debrief in a manner that respects the learner’s perspective while guiding them towards more critical self-reflection. This model fosters psychological safety by ensuring that feedback is delivered in a way that promotes learning without embarrassment or defensiveness (Rudolph et al., 2006).

- Non-Judgmental Approach with Good Judgment:

Unlike some debriefing methods that aim to be “non-judgmental,” Debriefing with Good Judgment asserts that facilitators must hold learners accountable to professional standards while remaining respectful. The difference lies in how feedback is delivered. Instead of masking judgments or being overly neutral, the facilitator provides direct feedback but frames it in a way that fosters understanding and reflection, rather than blame. This is where the “good judgment” aspect of the model becomes critical—it encourages open dialogue and creates a safe environment for learners to critically examine their performance (Rudolph et al., 2007).

- .Focus on Cognitive Frames:

This model is unique in its emphasis on cognitive frames—the thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions that shape how learners act during simulations. By exploring these cognitive frames, the facilitator can better understand why learners made certain decisions and help them adjust those frames to improve future performance. The inquiry component of the method specifically targets these cognitive frames, encouraging learners to identify and challenge assumptions that may have led to errors or misjudgments.

- Encouraging Reflection and Self-Assessment:

The advocacy-inquiry approach is designed to guide learners through the process of self-assessment. By posing thoughtful, open-ended questions, facilitators encourage learners to analyze their actions, uncover their reasoning, and recognize both strengths and areas for improvement. This approach supports the development of clinical reasoning and promotes lifelong reflective practice, essential components of competent healthcare providers.

- Psychological Safety:

One of the core strengths of the Debriefing with Good Judgment model is its commitment to fostering psychological safety. By ensuring that debriefing is respectful and non-threatening, learners feel safe to openly discuss their mistakes and uncertainties. This safety is critical for deep learning, as it reduces defensiveness and allows for more honest reflection and dialogue (Rudolph et al., 2014).

- Steps in the Debriefing Process

- Observation (Advocacy):

The facilitator begins by describing what they observed during the simulation in a neutral, factual manner. This could involve pointing out a specific action or decision made by the learner. For example, the facilitator might say, “I noticed that you administered the medication without confirming the patient’s allergies.”

2. Open-Ended Question (Inquiry):

After the observation, the facilitator follows up with a question that seeks to understand the learner’s thought process. The inquiry should be open-ended and non-judgmental. For instance, “Can you walk me through what you were thinking when you decided to administer the medication at that moment?”

3. Learner Reflection:

The learner responds to the inquiry, explaining their thought process and the rationale behind their actions. This is where the debriefing moves into self-reflection, allowing the learner to critically evaluate their decision-making and consider alternative approaches.

4. Discussion and Feedback:

The facilitator and learner engage in a discussion based on the learner’s reflections. The facilitator offers additional insights, feedback, or clarification, helping the learner identify areas for improvement and strategies for future scenarios.

5. Summary and Application:

The debriefing session concludes with a summary of key learning points. The facilitator helps the learner apply the lessons from the debriefing to future clinical situations, reinforcing the importance of continuous improvement and clinical reasoning.

- Evidence of Effectiveness:

Research on Debriefing with Good Judgment has demonstrated its effectiveness in enhancing learner engagement, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning. By balancing advocacy and inquiry, this model helps learners reflect deeply on their cognitive frames and decision-making processes, leading to improved performance in subsequent clinical scenarios (Rudolph et al., 2006). The method has been widely adopted in healthcare simulation education due to its focus on respectful, yet direct, feedback that promotes reflective learning.

Debriefing with Good Judgment, as an example of the Advocacy-Inquiry Model, is a powerful tool for fostering reflection, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning in healthcare simulations. It promotes an open, respectful dialogue between facilitators and learners, ensuring that debriefing sessions are productive and conducive to deep learning. By focusing on cognitive frames and using an inquiry-based approach, this method encourages learners to critically examine their actions and improve their clinical decision-making skills.

Examples

3. PEARLS Debriefing Model

Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS) is based Experiential Learning Theory and Transformational Learning. PEARLS integrates various debriefing techniques, including directive feedback, open-ended inquiry, and collaborative dialogue. It provides structure while allowing for flexibility based on learner needs. PEARLS has been shown to be effective in both formative and summative settings, encouraging reflective practice and performance improvement (Eppich & Cheng, 2015).PEARLS is a structured debriefing model designed to provide a flexible, evidence-based framework for debriefing after clinical simulations. Developed by Walter Eppich and Adam Cheng in 2015, the PEARLS model integrates multiple debriefing approaches, including directive feedback, learner self-assessment, and guided reflection, to enhance learning outcomes. It is rooted in experiential learning and reflective practice, ensuring that learners can engage in meaningful dialogue about their performance while fostering critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills.

Key Features of the PEARLS Model

- Flexibility and Integration of Multiple Debriefing Approaches:

One of the main advantages of PEARLS is its flexibility. The model incorporates various debriefing strategies, such as directive feedback (when the facilitator provides specific guidance), learner self-assessment (where learners reflect on their own performance), and guided reflection (where learners critically analyze their decisions and actions). This integration allows the debriefing to be tailored to the learners’ needs and the specific goals of the simulation scenario, making PEARLS adaptable to different learning environments and contexts (Eppich & Cheng, 2015).

- .Structured Debriefing Process:

The PEARLS model is organized into four phases that help guide the debriefing session:

- Reactions: In this initial phase, learners are encouraged to express their emotional responses to the simulation. This allows the group to release tension and prepares them to engage more constructively in the following stages.

2. Description: The facilitator leads a factual discussion of what happened during the simulation. This phase involves reviewing the scenario’s events, making sure that everyone has a shared understanding of what occurred.

3. Analysis: This is the most critical phase of the debriefing, where learners reflect on their performance, guided by the facilitator. The goal is to encourage learners to analyze their actions, explore the reasoning behind their decisions, and discuss alternative approaches. The facilitator uses open-ended questions and targeted feedback to promote reflection and critical thinking.

4. Summary: The debriefing session ends with a summary of key takeaways and lessons learned. The facilitator reinforces the most important points discussed during the debriefing and helps learners apply these lessons to future clinical practice (Eppich & Cheng, 2015).

- Blended Approach:

The PEARLS model takes a blended approach by incorporating elements from several established debriefing frameworks, including learner-centered approaches and facilitator-driven feedback. This blended nature ensures that learners are both actively engaged in self-reflection and receive valuable insights from their instructor. The facilitator can switch between providing directive feedback when necessary and guiding learners to self-assess, making PEARLS particularly effective for addressing both technical skills and cognitive processes (Cheng et al., 2016).

- Promoting Reflective Learning:

A key goal of PEARLS is to promote reflective learning. By guiding learners through structured reflection, PEARLS helps them connect their simulation experience to broader clinical knowledge and professional practice. This reflective process encourages the development of clinical reasoning skills and fosters a growth mindset, enabling learners to improve their performance in future clinical situations.

- Psychological Safety:

Similar to other successful debriefing models, PEARLS emphasizes the importance of psychological safety. Facilitators are trained to create a supportive and non-judgmental environment, allowing learners to openly discuss their mistakes and uncertainties without fear of embarrassment. This ensures that learners are more likely to engage in honest self-reflection and are better positioned to learn from their experiences (Cheng et al., 2016).

- Evidence of Effectiveness

Research shows that the PEARLS model is highly effective in promoting reflective learning, clinical reasoning, and skill acquisition. It has been adopted widely in healthcare education due to its versatility and ability to accommodate different learning styles and needs. The model’s emphasis on both self-assessment and facilitator guidance ensures that learners receive well-rounded feedback that addresses both technical performance and cognitive decision-making.

A study conducted by Cheng and colleagues (2016) highlighted the effectiveness of PEARLS in improving learners’ reflective practice and overall satisfaction with the debriefing process. Learners reported that the structured yet flexible approach of PEARLS allowed them to engage more deeply with the material and better understand their areas for improvement.

Conclusion

The PEARLS Debriefing Model is a highly adaptable and comprehensive framework that integrates multiple debriefing approaches to promote reflective learning and critical thinking in clinical simulations. Its structured process, flexibility, and emphasis on psychological safety make it an effective tool for enhancing learners’ clinical competence and preparing them for real-world healthcare settings.

Educator Resources

V. Evaluation of Debriefing

Evaluation of debriefing in simulations is crucial to ensure that the debriefing process meets its educational objectives and fosters effective learning outcomes. Evaluating debriefing involves assessing both the debriefing process itself and its impact on learner outcomes, such as critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and performance improvement. The evaluation process is essential for improving the quality of debriefing sessions and ensuring alignment with best practices.

1. Frameworks for Evaluation

Various models and tools have been developed to evaluate debriefing, ensuring that facilitators adhere to structured, evidence-based approaches. Some of the widely used frameworks for evaluating debriefing include:

•Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH): DASH is a validated tool used to evaluate the quality of debriefing sessions in healthcare simulations. It assesses six key components: establishing an engaging learning environment, structuring the debriefing, probing for understanding, exploring performance gaps, and encouraging reflective learning (Simon et al., 2009). Facilitators or external evaluators can use DASH to assess the effectiveness of debriefing and identify areas for improvement.

•Objective Structured Assessment of Debriefing (OSAD): OSAD is another tool designed to objectively assess debriefing. It focuses on evaluating various components, including the facilitator’s ability to create a supportive learning environment, ask open-ended questions, and provide constructive feedback (Arora et al., 2012). OSAD’s structured approach allows for a standardized evaluation of debriefing quality and consistency.

- The Debriefing for Meaningful Learning Evaluation Scale (DMLES) is another widely recognized tool used to evaluate debriefing sessions in healthcare education. DMLES is designed to assess the effectiveness of debriefing in fostering critical thinking and reflective learning. It evaluates how well the facilitator adheres to the principles of DML, which focuses on promoting deep reflection and improving clinical reasoning through structured debriefing (Dreifuerst, 2012).

2. Key Elements to Evaluate in Debriefing

When evaluating debriefing sessions, several key elements must be considered to ensure that the process facilitates reflective learning and promotes knowledge transfer:

•Facilitator Performance: The facilitator plays a crucial role in guiding the debriefing process. Evaluating the facilitator involves assessing their ability to create a psychologically safe environment, ask probing questions, provide constructive feedback, and encourage learners to critically reflect on their actions.

•Learner Engagement: Learner participation and engagement in the debriefing process are critical to its success. Evaluators should assess the level of learner involvement, including their willingness to share their thoughts, reflect on their performance, and discuss areas for improvement.

•Structure and Focus: Effective debriefing follows a structured approach that includes phases such as reaction, reflection, analysis, and summary (as seen in models like PEARLS and DML). Evaluation should focus on whether the debriefing is well-organized and whether it addresses key learning objectives, such as critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and application of knowledge.

•Learning Outcomes: The ultimate goal of debriefing is to enhance learning outcomes. Evaluation should examine whether learners have developed a deeper understanding of the simulation scenario, improved their decision-making skills, and applied theoretical knowledge to practice. Tools like self-assessment and post-simulation quizzes can help measure the effectiveness of debriefing in achieving these goals.

3. Methods for Evaluating Debriefing

Evaluating debriefing can be done using several methods, each providing unique insights into the effectiveness of the debriefing process:

•Self-Assessment: Learners can be asked to self-assess their experience during the debriefing session. This can involve reflecting on the clarity of the feedback, the relevance of the discussion, and their personal learning outcomes. Self-assessment helps learners take ownership of their learning and provides facilitators with feedback on how well the debriefing met learner needs.

•Peer Evaluation: Peer evaluation can be used to assess both learner and facilitator performance. Having peers observe and evaluate the debriefing process can provide valuable insights into the facilitator’s ability to guide the session and promote reflection.

•Direct Observation by External Evaluators: Using external evaluators to observe debriefing sessions provides an objective assessment of the process. These evaluators can use standardized tools like DASH or OSAD to score the session and provide feedback on its effectiveness.

4. Challenges in Evaluation

Evaluating debriefing can be challenging due to the subjective nature of reflection and the variability in facilitator performance. To overcome these challenges, it is important to use validated tools like DASH and OSAD, which provide structured frameworks for evaluation and minimize bias. Additionally, ensuring that facilitators are trained in debriefing methods and regularly receive feedback on their performance can help maintain the quality and consistency of debriefing sessions.

5. Continuous Improvement

Evaluation of debriefing should not be a one-time event. Instead, it should be part of an ongoing process of continuous improvement. Facilitators should regularly review feedback from learners, peers, and external evaluators to refine their debriefing techniques and improve the overall effectiveness of simulation-based learning. Regularly incorporating evaluation into simulation programs ensures that debriefing remains a dynamic and evolving process that adapts to the needs of learners and educational objectives.

Conclusion

The evaluation of debriefing in clinical simulations is essential for maintaining high standards of simulation-based education. Using validated tools and frameworks like DASH and OSAD allows educators to assess debriefing sessions objectively and ensure that they promote critical reflection and clinical reasoning. Through continuous evaluation, facilitators can improve their debriefing techniques and enhance learning outcomes for students in healthcare education.

Tools for Evaluating Debriefing

VI. Debriefing in various simulation education contexts

Debriefing is an essential process in educational, clinical, and training contexts, allowing participants to reflect on experiences, discuss actions taken, and improve future performance. The method of debriefing can vary significantly based on the setting, number of facilitators, and the medium used for simulations. Here, we explore various approaches to debriefing, including multiple debriefers, virtual simulations, and other unique scenarios.

- Deebriefing with multiple debriefers ( co-debriefing)

In settings where complex situations are simulated—such as medical emergencies or multi-disciplinary team training—having multiple debriefers can enhance the debriefing experience. This approach allows for diverse perspectives and expertise, such as:

- Role Allocation: Each debriefer may focus on different aspects of the simulation, such as clinical skills, teamwork, communication, or ethical considerations.

- Structured Format: Utilizing frameworks like the “Three-Phase” model (what happened, why it happened, how to improve) helps ensure that all critical areas are covered.

- Facilitated Interaction: Debriefers encourage dialogue among participants, fostering an open environment where everyone can share insights and learn from each other.

The known benefits of co-debriefing or multiple debriefers include:

- Enhanced learning from varied expertise.

- Richer discussions due to multiple viewpoints.

- Improved participant engagement and reflection.

Educator Resource:

2. Debriefing in Virtual Simulations

With the rise of technology, virtual simulations have become common, especially in healthcare training. Debriefing in this context can be challenging due to the lack of physical presence but can be equally effective when executed thoughtfully. Debriefers need to consider:

- Immediate Feedback: Debriefing often occurs right after the simulation, utilizing recorded sessions to analyze participant performance.

- Interactive Platforms: Using virtual meeting tools (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams) allows for real-time interaction. Breakout rooms can facilitate smaller group discussions.

- Facilitator Preparation: Debriefers need to be adept with technology and familiar with the simulation platform to guide discussions effectively.

Before debriefing virtual simulations, facilitators have the opportunity to review recorded simulations for detailed analysis.

Educator Resource

Debriefing is a multifaceted process that can significantly enhance learning and performance across various fields. Whether utilizing multiple debriefers, adapting to virtual formats, conducting sessions in high-stress environments, or employing peer-led discussions, the core objective remains the same: to facilitate reflection, foster learning, and improve future performance. By tailoring the debriefing approach to the specific context and participants, facilitators can maximize the effectiveness of this crucial learning tool.

Learning Exercises: Practice debriefing structured methods

- Observe the clinical scenario- find the link below.

- Plan* your debriefing using: a) DML b) Advocacy-Inquiry-Debriefing with Good Judgment c) PEARLS

*Plan your questions according to the phases of debriefing ( method-specific)

Chapter Summary and Key Takeaways

- Debriefing is a structured, facilitated discussion following a simulation experience, where participants reflect on their actions, decisions, and outcomes. The aim is to promote learning through critical thinking, analysis, and reflective practice. It is considered a crucial part of simulation-based education, as it transforms the simulation experience into an opportunity for deeper learning.

- Debriefing is integral to effective simulation education because it allows learners to reflect on their performance in a safe environment, make sense of their actions, and apply those insights to future clinical situations. Research shows that debriefing promotes improved clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and self-awareness, leading to better decision-making in real-world clinical practice (Dreifuerst, 2012; Rudolph et al., 2006). It also enhances retention of skills, procedural knowledge, and interprofessional communication.

- The INACSL Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: Debriefing outlines evidence-based guidelines for conducting effective debriefing sessions. These standards emphasize the importance of structured debriefing, psychological safety, learner engagement, and alignment with learning objectives. Facilitators are encouraged to follow a systematic approach to debriefing, ensuring consistency and quality across simulation programs (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

- Debriefing is undepinned by educational theories and supported by empirical evidence

- There are several proven methods that are effective in structuring debriefing to meet learner outcomes and are supported by research and educational theories.

- Evaluating the quality and effectiveness of debriefing is essential for ensuring that learning objectives are met. Common evaluation tools include:

- Conclusion:Debriefing is a vital aspect of simulation-based learning that transforms simulated clinical experiences into opportunities for meaningful reflection and professional development. Grounded in educational theory, supported by evidence-based models, and guided by established standards, effective debriefing enhances clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and preparedness for real-world healthcare settings. Regular evaluation of debriefing ensures that it remains an impactful learning tool for healthcare professionals.

References:

Arora, S., Ahmed, M., Paige, J., et al. (2012). Objective Structured Assessment of Debriefing (OSAD): Bringing science to the art of debriefing in surgery. Annals of Surgery, 256(6), 982-988.

Cheng, A., Eppich, W., Grant, V., Sherbino, J., Zendejas, B., & Cook, D. A. (2016). Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education, 48(7), 657-666.

Cheng, Adam MD, FRCPC, FAAP; Palaganas, Janice PhD, RN, NP; Eppich, Walter MD, MEd; Rudolph, Jenny PhD; Robinson, Traci RN, BN; Grant, Vincent MD, FRCPC. Co-debriefing for Simulation-based Education: A Primer for Facilitators. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare 10(2):p 69-75, April 2015. | DOI: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000077

Dreifuerst, K. T. (2012). Debriefing for Meaningful Learning: Fostering Development of Clinical Reasoning Through Simulation. Journal of Nursing Education, 51(6), 326-333.

Dreifuerst, K. T. (2015). Getting Started With Debriefing for Meaningful Learning. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(5), 268-275.

Eppich, W., & Cheng, A. (2015). Promoting excellence and reflective learning in simulation (PEARLS): Development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simulation in Healthcare, 10(2), 106-115.

Fey, M. K., & Jenkins, L. S. (2015). Debriefing practices in nursing education programs: Results from a national study. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(6), 361-366.

INACSL Standards Committee. (2021). Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: Debriefing. Clinical Simulation in Nursing.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice-Hall.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education Quarterly, 28(2), 100-110.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5-12

Rudolph, J. W., Simon, R., Dufresne, R. L., & Raemer, D. B. (2006). There’s No Such Thing as “Nonjudgmental” Debriefing: A Theory and Method for Debriefing with Good Judgment. Simulation in Healthcare, 1(1), 49-55.

Rudolph, J. W., Simon, R., Raemer, D. B., & Eppich, W. J. (2007). Debriefing as formative assessment: Closing performance gaps in medical education. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(11), 1010-1016.

Rudolph, J. W., Raemer, D. B., & Simon, R. (2014). Establishing a Safe Container for Learning in Simulation: The Role of the Facilitator. Simulation in Healthcare, 9(6), 339-349.

Simon, R., Raemer, D. B., & Rudolph, J. W. (2009). Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare: Development and Psychometrics. Simulation in Healthcare, 4(4), 201-207.

Simon, R., Raemer, D. B., & Rudolph, J. W. (2009). Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare: Development and Psychometrics. Simulation in Healthcare, 4(3), 206-215.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. Jossey-Bass.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.