3 Curriculum Integration of Simulations

Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving healthcare environment, prelicensure nursing education must prepare students to be skilled, confident, and adaptable practitioners. One of the most transformative approaches to achieving this goal is the integration of simulation into the nursing curriculum. Simulation-based education offers a safe, controlled environment where students can practice essential nursing skills, apply theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios, and develop critical thinking abilities. The use of high-fidelity simulation (HFS) creates immersive, realistic scenarios that replicate clinical settings, offering students the opportunity to practice and refine skills in a no-risk environment (Cant & Cooper, 2010; Jeffries, 2012).

Aligned with the Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™(HSSOBP) from the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL), integrating simulation into nursing curricula enhances student learning by standardizing the development, implementation, and evaluation of simulation-based activities (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021). These standards emphasize the importance of simulation as a teaching strategy, requiring careful scenario development, facilitation, and debriefing to ensure that students can transfer knowledge and skills to clinical practice. The standards also advocate for structured prebriefing and debriefing sessions, which are critical to solidifying learning outcomes and reinforcing student performance during and after simulation exercises (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

This chapter focuses on the systematic integration of simulation into nursing education, ensuring alignment with curriculum goals, clinical outcomes, and the INACSL standards. Simulation bridges the gap between classroom learning and hands-on clinical practice, which is particularly vital as clinical placements may become limited or unpredictable (Hayden et al., 2014). Through carefully designed and implemented simulation experiences, nursing students can develop clinical judgment, communication skills, and confidence, which are essential for delivering safe, patient-centered care.

Learning Objective 1:

Analyze the role of simulation in nursing education.

Learning Objective 2:

Examine the process of integrating simulation into a prelicensure nursing curriculum.

Learning Objective 3:

Utilize the INACSL Healthcare simulation standards in planning effective simulation-based education.

Through this chapter, you will gain insight into how simulation-based education enhances nursing competencies. Simulation not only addresses technical skills but also reinforces the critical competencies of communication, teamwork, and leadership—that are vital in the ever-changing landscape of healthcare. Following the INACSL HSSOBP ensures that simulation is used to its full potential, providing a consistent, evidence-based approach to developing nursing students’ clinical skills and judgment. Simulation is an integral component of nursing education because it allows for a safe, timely, and prescriptive approach to meet learning objectives at the levels of simulations, courses and academic programs (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021). There is adequate evidence that supports the ability of simulations to provide rich learning experiences, especially high value low access clinical situations to learners. Random, unintentional simulation experiences that are not carefully integrated into an organized curriculum can result in ineffective and inefficient use of time for both educators and learners (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021; Herrington & Schneiderith, 2017; Howard et al, 2019; Thomas et al, 2016).

Systematic integration of simulations is needed in designing curricula in academic and professional practice settings. Simulation-based education is a costly educational modality, and the maximum benefits can be achieved, when simulations are well integrated in the curriculum to meet simulation objectives, course and program objectives (Masters, 2014). Like any undertaking in educational programs, a curricular integration framework must be used, and a curricular plan be made available for implementation and evaluation. This learning module unfolds to discuss the concept of curricular integration, theoretical and empirical bases for simulation-based education in nursing curriculum, and essential steps and elements of curricular integration. Exercises to check knowledge and apply learned concepts are included along with video resources to further highlight concepts of curricular simulation integration.

I. Curriculum Integration of Simulations

Curriculum integration refers to the process of thoughtfully connecting various content areas within an educational program, ensuring that learning experiences are interconnected and aligned with overarching goals and outcomes. In simulation education, it is the coordinated and purposeful use of simulation-based learning methods to meet predetermined learning goals within an approved or existing curriculum (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021).In nursing education, this concept is crucial for linking educational theories to practice, allowing students to develop a comprehensive understanding of the various facets of patient care. For example, integrating clinical simulations into a nursing curriculum helps students apply theoretical knowledge to real-life scenarios, promoting critical thinking and skill development (Jeffries, 2012). Curriculum integration also emphasizes the need for cohesive learning across different courses, where students can relate,for example, where students can relate pharmacology to pathophysiology or apply leadership principles in clinical practice (Giddens, 2015). This holistic approach to education ensures that students are better prepared to face the complexities of healthcare, as it promotes continuity of learning and bridges the gaps between different areas of study.

In curriculum integration, simulations are incorporated in each course or level to promote psychomotor, cognitive and affective domains of learning (Schram & Aschenbenner, 2014). Simulations are used in different settings in nursing education; from simulated clinical situations to replace part (or all) of clinical experiences that traditionally happen in real patient care situations, to simulations used to illustrate clinical experiences in the classroom. The National League of Nursing (NLN) Vision Series (National League for Nursing, 2015) articulates the vision of using simulations across the curriculum: simulation pedagogy transcending the simulation laboratory and viewed as an innovative way, a break from the long held nursing education traditions.

Check your Knowledge

Nurse Educator MUST READ: Open the link below to read the relationship of curriculum and simulations:

Curriculum and Simulation: Are they related?

Knowledge Check:

II: Theoretical and Empirical Support for Simulation-Based Education in Nursing

The integration of simulations into a nursing curriculum must be grounded in educational theories and supported by evidence-based practices to maximize its effectiveness in enhancing student learning. Ensuring that simulation integration is guided by well-established educational theories and supported by empirical research is essential for creating a curriculum that fosters critical thinking, skills acquisition, and student preparedness for real-world clinical practice.

A. Empirical Bases

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) National Simulation Study generated support of simulations replacing 25%-50% of traditional clinical experiences (Hayden et al, 2014). Empirical support of the use of simulations in clinical education has advanced and has been used to support standards of best healthcare simulations (INACSL, 201) and guidelines for using simulations in nursing education (NCSBN, 2016). The NLN (2015) advocates for simulation and debriefing across the curriculum; and NCSBN (2016) Simulation Guidelines for prelicensure nursing programs cite several systematic reviews and the National Simulation Study to support the use of simulations in nursing curriculum:

- Simulation as an effective teaching method to enhance cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills ( Mishra et al., 2023)

- Integrated learning, critical thinking, and optimal decision-making skills help nurses to provide quality health care. This can be achieved through the inclusion of simulation in the education process (Koukourikos et al., 2021)

- Lapkin et al. (2010) conducted a systematic review of eight studies that met their inclusion criteria. They found that simulation improved critical thinking, performance of skills, knowledge of the subject matter and an increase in clinical reasoning in certain areas. Two integrative reviews of undergraduate nursing’s use of simulation focused on patient safety.

- Berndt (2014) reviewed seventeen studies, including 3 systematic reviews. Their findings support the use of simulation as an educational intervention to teach patient safety in nursing, particularly when other clinical experiences aren’t available.

- Fisher & King (2013) conducted an integrative review related to patient safety in that they examined 18 studies preparing students, through simulation, to respond to deteriorating patients. They found that, in general, confidence, clinical judgment, knowledge and competence increased through the use of simulation.

- The largest and most comprehensive study to date examining student outcomes when simulation was substituted for up to and including 50% simulation was NCSBN’s National Simulation Study (Hayden et al., 2014). This longitudinal, randomized, controlled study replaced clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. In ten nursing programs from across the country (five BSN and five ADN), students were followed through all clinical courses in their nursing programs as well as through their first six months of practice. The study provided evidence that when substituting clinical experiences with up to 50% simulation, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups using 10% or less of simulation (control), 25% simulation or 50% simulation with regard to knowledge acquisition and clinical performance. In conclusion, the literature provides evidence that simulation is a pedagogy that may be integrated across the prelicensure curriculum, provided that faculty are adequately trained, committed and in sufficient numbers; when there is a dedicated simulation lab which has appropriate resources; when the vignettes are realistically and appropriately designed; and when debriefing is based on a theoretical model.

Simulation research has advanced to what it is today, establishing simulation-based education’s relevance and necessity in nursing education. It is important for nurse educators, as they attempt to integrate simulations in the nursing curriculum to be cognizant of current empirical evidence and guidelines for using simulations in nursing education.

B. Theoretical Bases

The theoretical bases of simulation are sound learning theories, and are frequently used in simulation education and research:

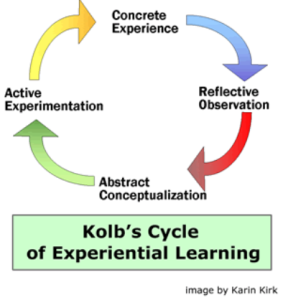

- Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory:

Kolb describes a cognitive learning process where individuals have concrete experiences, followed by reflection, generation of abstract conceptualizations and application of new knowledge to future practice (Kolb, 1984). Kolb’s theory resonates with modern nursing simulation: active participation in a simulation experience (concrete experience), followed by reflective observation and abstract conceptualization that occur in debriefing of simulations. The cycle is completed through learners active experimentation of learned practice in another simulation or in actual patient care.

Reflection Question

How can nurse educators use Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory in planning for real and simulated students’ clinical learning experiences?

2. Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), developed by John Sweller, posits that the human brain has a limited capacity for processing information, especially in working memory, which can only hold a small amount of information at any given time. CLT identifies three types of cognitive load: intrinsic load, which is related to the inherent complexity of the material being learned; extraneous load, which refers to the way information is presented, and how it may hinder learning if it’s overly complex or unclear; and germane load, which is the cognitive effort directed toward learning and understanding the material itself (Sweller, 1988).

Effective instructional design, such as simulations in nursing education, seeks to manage these types of cognitive load by reducing extraneous load (e.g., removing unnecessary distractions) and optimizing intrinsic load (e.g., scaffolding complex tasks). By doing so, learners can focus their cognitive resources on germane processing, thereby enhancing their ability to understand and retain new information. CLT has important implications for educational practice, as poorly designed instruction can overwhelm students and impede learning, while properly aligned methods can enhance comprehension and skill acquisition (Chandler & Sweller, 1991).

Cognitive Load Theory in a nutshell:

The application of Cognitive Load Theory is discussed in the following video. Cognitive load theory underpins simulation scenario design.

Cognitive load theory underpins standards of best practice of simulations, emphasizing the need to understand the science of learning in designing and implementing simulations that are systematically aligned in the curriculum.

Key Takeaways

As nurse educators, how do we take into account intrinsic load, germane load and extraneous load of our learners in the design and facilitation of simulations? What are the implications in curricular integration?

- What are your prebriefing plans?

- How simple or complex are the simulations in each course? Are they appropriate for the learner’s level in the program?

- Reflect on other ways to use this frame (Cognitive Load Theory) in your curriculum.

3. NLN Jeffries Simulation Theory

The following are notable points of the theory based on NLN Jeffries Simulation Theory: Brief Narrative Description (Jeffries et al., 2015).

- Context refers to contextual factors that need to be taken into consideration when designing and evaluating simulations such as setting and overarching purpose of simulation.

- Background refers to the theoretical perspective for the specific simulation experience and how the simulation fits into the larger curriculum.

- Design includes specific learning objectives that guide the development or selection of activities and scenarios with appropriate content and problem-solving complexity (physical and conceptual fidelity, roles, scenario progression, and prebriefing and debriefing strategies)

- Simulation Experience is characterized by an environment that is experiential, collaborative and learner-centered (psychological safety, suspension of disbelief)

- Facilitator and Educational Strategies in the context of the simulation experience is a dynamic interaction between facilitator and participant. Some of the important facilitator attributes include skill, educational techniques and preparation. For example: “The facilitator responds to emerging participant needs during the simulation experience by adjusting educational strategies such as altering the planned progression and timing of activities and providing appropriate feedback in the form of cues (during) and debriefing (toward the end) of the simulation experience.”

- Participant innate attributes include age, gender, level of anxiety and self-confidence, whereas preparedness for simulation is modifiable.

- Outcomes: a) Participant outcomes include reaction, learning, behavior; b) Patient and c) System

Simulation Educator’s Essential Resource:

4. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

Lev Vygotsky’s theory of social constructivism underpins simulation-based education by emphasizing the importance of social interaction, collaboration, and guided learning in the development of higher cognitive processes. Vygotsky introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which refers to the difference between what a learner can achieve independently and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable individual (Vygotsky, 1978). In simulation-based education, this theory is reflected in the interaction between learners and facilitators or peers during the simulation experience and debriefing sessions.

In nursing simulations, students are often placed in scenarios where they can practice complex clinical skills in a safe, controlled environment with support from instructors or more experienced peers, aligning with Vygotsky’s idea that learning is best facilitated through scaffolded experiences. The debriefing process after a simulation also reflects Vygotsky’s belief in the power of social interaction in learning, as learners critically reflect on their actions, receive feedback, and discuss improvements with their peers and instructors (Fey & Jenkins, 2015).

Furthermore, Vygotsky’s idea of internalization—where learners first engage in activities externally (through interaction with others) and then gradually internalize knowledge and skills—is essential in simulation-based education. Simulations allow learners to externalize knowledge through hands-on practice in realistic scenarios, which they later internalize as part of their clinical judgment and professional practice (Jeffries, 2012).

Watch this video to learn: How to we facilitate our learners’ higher mental functions through simulations?

Key Takeaways

In planning for Curriculum Integration:

- Our plans to integrate simulations in existing simulation must be based in sound educational theories

- The planning, design, implementation and evaluation of simulations must be planned in curricular integration using the NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory.

III. Curriculum Integration: Frameworks and Process

Integrating simulation into nursing curricula requires a strategic approach grounded in curriculum integration frameworks that ensure learning experiences are cohesive, purposeful, and aligned with program outcomes. Curriculum integration frameworks such as Backwards Design and Concept-Based Learning offer a structured way to align simulations with educational objectives and competencies.

Backwards Design Framework:

Developed by Wiggins and McTighe (1998), the Backwards Design framework begins by identifying the desired learning outcomes, then determining the appropriate assessments, and finally, designing the instructional activities, such as simulations, to achieve those outcomes. In the context of simulation, this means that nursing programs first identify the key competencies students need to demonstrate, such as clinical judgment, safe patient handling, or effective communication. The next step is designing assessments that measure these competencies in action, often through simulation-based evaluations. Finally, simulation scenarios are tailored to meet the learning objectives and provide students with the opportunity to practice and refine these skills in a controlled, real-life environment. This ensures that simulation activities are not stand-alone exercises but are integrated into the broader curriculum with clear learning objectives and assessment methods in place.

Concept-Based Learning Framework:

In a concept-based curriculum (Giddens, 2015), the focus shifts from memorizing facts to understanding overarching concepts that span multiple areas of nursing practice. This framework supports the integration of simulations by allowing educators to design simulation scenarios that cover broad, essential nursing concepts such as safety, patient-centered care, and teamwork. Instead of siloing content into separate classes or skill labs, concept-based curricula use simulations to explore these critical themes in diverse, complex scenarios. For instance, a single simulation could cover several critical nursing concepts by requiring students to care for a post-operative patient who also has complex psychosocial needs, thereby encouraging deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of nursing knowledge.

Competency-Based Education (CBE) Framework:

Competency-based education (CBE) frameworks also underpin the integration of simulation by focusing on the attainment of core competencies rather than just the accumulation of credit hours or classroom time (Ten Cate et al., 2015). CBE ensures that students not only understand the theoretical aspects of nursing but are also competent in the skills necessary to provide safe and effective patient care. Simulation fits seamlessly into this framework by offering a means to assess competencies in real-time, allowing students to practice skills such as administering medications, performing assessments, and making critical decisions in a simulated clinical environment.

By using these curriculum integration frameworks, nursing educators can ensure that simulations are not just added to the curriculum as isolated activities but are embedded within a coherent educational strategy. This approach fosters critical thinking, skill development, and practical application in a way that is directly aligned with the goals of nursing education.

This video discusses curriculum development for healthcare professions curriculum development, including integration of simulations (GWU School of Nursing open educational resource):

A. Needs Assessment

(Kern’s Steps 1 and 2)

Understanding the following required elements is necessary to determine the need to integrate simulations in the curriculum:

- Underlying cause of concern

- Organizational analysis

- Stakeholders’ survey

- Program outcome data

- Self-study comparing current practices to INACSL standards of healthcare simulations

- Accreditation reports

- Standardized test results

- Didactic Examinations

- Feedback from clinical partners

- QSEN competencies

- Learners Needs and learning style preferences

Understanding the current landscape of healthcare and societal needs will help us guide needs assessment for curricular development and integration of simulations.

Educating Nurses of the Future

-

The Need for Nursing Education on Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity

-

The Need for Integration of Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity into Nursing Education

-

The Need for BSN-Prepared Nurses

-

The Need for PhD-Prepared Nurses

-

Delivering Person-Centered Care and Education to Diverse Populations

-

Cultural Humility

-

Implicit Bias

-

Learning to Collaborate Across Professions, Disciplines, and Sectors

-

Continually Adapting to New Technologies

Curricular Need

A statement indicating the desired state, compared to current state, supported by objective data and standards of best practice, is needed to propose a curricular integration of simulations in the curriculum.

B. Goals and Objectives- Curricular mapping

(Kern’s step 3)

The learning goals and objectives of simulations must be linked to content, courses, and the overarching program outcomes. A curricular map will allow faculty to scaffold simulation experiences and build and content and complexity from previous courses. Scaffolding allows learners to demonstrate knowledge, skills and attitudes, add new knowledge, and apply new material. Scaffolding promotes learning efficiency (Franklin & Blodgett, 2020). Curricular mapping requires input from faculty across the curriculum along with simulation faculty. Simulations objectives must be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time bound (SMART), and must be linked to unit objectives, course objectives and end of program student learning outcomes.

- Determine how content can be thoughtfully linked to context

- Lay out a curricular map to explore areas needing improvement

- Match simulation to didactic content for each course

Curricular alignment is a linear configuration between program outcomes, course outcomes, and simulation outcomes. If program outcomes drive course outcomes, then course outcomes should drive simulation outcomes. If we design simulations that adhere to the Standards, then all simulations should clearly map back to program outcomes. Simulations are no longer run to compensate for clinical time or replace hours lost to other activities, but instead are designed to address specific course outcomes (Schneidereith & Beroz, 2017).

Backward Design

C. Educational Strategies

(Kern’s Step 4)

- Simulation is an educational strategy that is framed by educational theories, including constructivism, experiential learning, and andragogy. Current standards of healthcare simulations provide guidance to educators on design, implementation, and evaluation of this teaching-learning modality. See HEALTHCARE SIMULATION STANDARDS OF BEST PRACTICE™

- Planning and Sequencing Simulation Experiences: Thoughtful curricular integration reduces the variability brought about by different clinical experiences; nurse educators will need to plan to include simulations that allow students to safely practice frequently required competencies along with the ability to practice clinical situations that students are not otherwise able to practice independently because of safety and legal considerations. Nurse Educators will need to plan and make decisions on writing simulation scenarios or utilize peer reviewed scenarios. Both will require alignment with course and program learning objectives.

- Simulations are a powerful teaching and learning modality beyond the simulation laboratory. An example is illustrated in the resources below:

D. Implementation

( Kern’s Step 5)

- The simulation experience should have maximum realism so that students do not spend cognitive energy understanding what is real and what must be imagined (Franklin & Blodgett, 2020; Screws & Cason, 2019). This has huge implications on budgeting operations; faculty must present a strong business case on the maximum return or gains in the integration of simulations in the curriculum.

- Utilizing Simulation Education Resources: Although simulations can curricular needs and gaps, available and potential resources must be taken into consideration such as: faculty and administrative support, size of student population/cohorts, clinical hours, clinical to simulation hours ratio, faculty competencies, simulation space and set up, and debriefing space.

- It is crucial to match the level of fidelity and the level of learners’ level of experience; it is important that the level of fidelity matches both scenario objectives and learners’ needs. Simulation modalities and their availability are important factors to consider in the implementation of simulations. Various modalities include low to high fidelity manikins, standardized patients (actors), tasks trainers, virtual simulation modalities, visual aids and computer systems and competent staff. These are elements that will enhance implementation of simulation-based curriculum.

Key Takeaways

Standardized Patient (SP) methodology plays a critical role in simulation-based education, providing an authentic, human-centered approach to clinical training. SPs are trained individuals who simulate real patient conditions, allowing students to engage in clinical encounters that replicate real-world scenarios (Barrows, 1993). This methodology enhances the learning experience by incorporating dynamic human interaction, which fosters the development of communication, interpersonal, and clinical assessment skills in a controlled and safe environment (Lewis et al., 2017).

In planning simulation-based education, incorporating SP methodology allows educators to tailor scenarios to meet specific learning objectives, such as developing cultural competence, therapeutic communication, and clinical decision-making. The presence of SPs also facilitates immediate feedback from both the simulated patient and instructors, which is key to reflective learning and professional development. Moreover, SP-based simulations provide the flexibility to standardize learning experiences across student cohorts, ensuring consistency in the exposure to clinical situations (Gaba, 2004). To effectively integrate SP methodology, educators must ensure adequate training for the SPs, create detailed simulation scripts, and plan for debriefing sessions to help learners synthesize the skills practiced during the encounter.

Highlight on Standards of Best Practice in Simulations and Standardized Patients/Human Players

The Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE) Standards of Best Practice (SOBP)

Podcast: Learning From Our Failures: SPs from Center for Medical Simulation

Reflection: What special considerations do we consider as nurse educators in using Standardized Patients in the Curriculum?

VIRTUAL SIMULATION

Tolarba (2021) states virtual simulation (VS) is more effective than simulation in a nursing lab; VS improves affective and cognitive domains of learning, increases students’ clinical skills, technology skills, confidence, and enjoyment.

What is VS and how can it be integrated into curriculum? How can you evaluate it’s effectiveness?

This is a comprehensive educator’s toolkit on the use of virtual simulations in healthcare

F. Evaluation of Simulations

(Kern’s Step 6)

- Well-defined learning outcomes are critical to the success of a simulation activity. Yet outcomes, in turn, should get educators to consider how they’re going to evaluate their simulations, similar to how educators should “begin with the end in mind” when

programming simulation activities. Tagliareni and Forneris (2016) believe there should also be a focus on evaluation of the simulation activities overall. To that end, they recommend faculty and curriculum developers build in evaluations that evaluate:- 1. total number of anticipated simulations

- 2. student learning

- 3. students’ simulation experience (whether or not the experience is being implemented consistently across classes and courses, for example)

- 4. the simulation program as a whole (how effective it is at positively impacting outcomes, for example)

- 5. faculty development including roles and responsibilities and best practices in using simulation

- 6. evaluation of faculty facilitation (how does it compare to the facilitation conducted in the classroom?) (Tagliareni & Forneris, 2017).

- Evaluation results data for each individual simulation encounter should be analyzed and incorporated back into the course. Analysis should address whether the activity met the learning outcome for the course, using quantitative data (which many of the instruments referenced above are designed to measure) so that faculty can quantify learning and thus, more easily map the data to student, course, and curriculum outcomes (Tagliareni & Forneris, 2016).

- The NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory frames the needs and elements of evaluation of simulations (Jeffries, et al., 2016). A repository of instruments is found in INACSL Repository of Instruments used in Simulation Research and the standards are written in Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM Evaluation of Learning and Performance

Exercises

Question: What lessons can we take from the article that will lead our programs to successful integration of simulations?

IV. Simulations Across the Curriculum

VI. Additional Resources:

2. MCSRC Summer 2020 Speaker Series: Curricular Integration by Tonya Scheneiderith

3. Video Series: Debriefing in the Classroom and beyond:

- Debriefing in the classroom

2. Debriefing Post-Clinical Day:

3. Debriefing a critical incident in clinicals:

References:

Aul, K., Bagnall, L., Bumbach, M. D., Gannon, J., Shipman, S., McDaniel, A., & Keenan, G. (2021). A key to transforming a nursing curriculum: Integrating a continuous improvement simulation expansion strategy. SAGE Open Nursing, 7, 2377960821998524. https://doi.org/10.1177/2377960821998524

Cant, R. P., & Cooper, S. J. (2010). Simulation-based learning in nurse education: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1), 3-15.

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293-332.

Gaba, D. M. (2004). The future vision of simulation in healthcare. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(suppl 1), i2-i10.

Franklin, A. E., & Blodgett, N. P. (2020). Simulation in undergraduate education. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 39(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.39.3

Hayden, J. K., Smiley, R. A., Alexander, M., Kardong-Edgren, S., & Jeffries, P. R. (2014). The NCSBN National Simulation Study: A longitudinal, randomized, controlled study replacing clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 5(2), S3-S40.

INACSL Standards Committee. (2021). Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 1-54.

Jeffries, P. R., Rodgers, B., & Adamson, K. (2015). NLN Jeffries simulation theory: Brief narrative description. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(5), 292–293. https://doi.org/10.5480/1536-5026-36.5.292

Masters K. (2014). Journey toward integration of simulation in a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. The Journal of Nursing Education, 53(2), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20131209-03.

Mishra, R., Hemlata, & Trivedi, D. (2023). Simulation-based learning in nursing curriculum- time to prepare quality nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 9(5), e16014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16014

National League for Nursing (2015). NLN vision series: A vision for teaching with simulation. https://www.nln.org/docs/default-source/uploadedfiles/about/nln-vision-series-position-statements/vision-statement-a-vision-for-teaching-with-simulation.pdf?sfvrsn=e847da0d_0

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285.

Tagliareni, E & Forneris, Susan (2016). Curriculum and simulation: Are they related? Wolters Kluwer/National League for Nursing. White Paper.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Fey, M. K., & Jenkins, L. S. (2015). Debriefing practices in nursing education programs: Results from a national study. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(6), 361-366.

Jeffries, P. R. (Ed.). (2012). Simulation in nursing education: From conceptualization to evaluation. National League for Nursing.

References:

•Jeffries, P. R. (Ed.). (2012). Simulation in nursing education: From conceptualization to evaluation. National League for Nursing.

•Waxman, K. T. (2010). The development of evidence-based clinical simulation scenarios: Guidelines for nurse educators. Springer Publishing Company.

•Jeffries, P. R. (Ed.). (2012). Simulation in nursing education: From conceptualization to evaluation. National League for Nursing.

•Giddens, J. F. (2015). Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking nurse. Elsevier.