Nonverbal Communication

Your brother comes home from school and walks through the door. Without saying a word, he walks to the fridge, gets a drink, and turns to head for the couch in the family room. Once there, he plops down, stares straight ahead, and sighs. You notice that he sits there in silence for the next few minutes. In this time, he never speaks a word. Is he communicating? If your answer is yes, how would you interpret his actions? How do you think he is feeling? What types of nonverbal communication was your brother using? Like verbal communication, nonverbal communication is essential in our everyday interactions. Remember that verbal and nonverbal communication are the two primary channels we study in the field of Communication. While nonverbal and verbal communications have many similar functions, nonverbal communication has its own set of functions for helping us communicate with each other. Before we get into the types and functions of nonverbal communication, let’s define nonverbal communication to better understand how it is used in this text.

DEFINING NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Like verbal communication, we use nonverbal communication to share meaning with others. Just as there are many definitions for verbal communication, there are also many ways to define nonverbal communication, let’s look at a few.

Verbal communication researchers Burgoon, Buller, and Woodall define nonverbal behaviors as “typically sent with intent, are used with regularity among members of a social community, are typically interpreted as intentional, and have consensually recognized interpretations”. In our opinion, this sounds too much like verbal communication, and might best be described as symbolic and systematic nonverbal communication.

Mead differentiated between what he termed as “gesture” versus “significant symbol,” while Buck and VanLear took Mead’s idea and argued that “gestures are not symbolic in that their relationship to their referents is not arbitrary,” a fundamental distinction between verbal and nonverbal communication (524). Think of all the ways you unconsciously move your body throughout the day. For example, you probably do not sit in your classes and think constantly about your nonverbal behaviors. Instead, much of the way you present yourself nonverbally in your classes is done unconsciously. Even so, others can derive meaning from your nonverbal behaviors whether they are intentional or not. For example, professors watch their students’ nonverbal communication in class (such as slouching, leaning back in the chair, or looking at their watch) and make assumptions about them (they are bored, tired, or worrying about a test in another class). These assumptions are often based on acts that are typically done unintentionally.

While we certainly use nonverbal communication consciously at times to generate and share particular meanings, when examined closely, it should be apparent that this channel of communication is not the same as verbal communication which is “an agreed-upon rule-governed system of symbols.” Rather, nonverbal communication is most often spontaneous, unintentional, and may not follow formalized symbolic rule systems.

Differences Between Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

There are four fundamental differences between verbal and nonverbal communication. The first difference between verbal and nonverbal communication is that we use a single channel (words) when we communicate verbally versus multiple channels when we communicate nonverbally. Try this exercise! Say your first and last name at the same time. You quickly find that this is an impossible task. Now, pat the top of your head with your right hand, wave with your left hand, smile, shrug your shoulders, and chew gum at the same time. While goofy and awkward, our ability to do this demonstrates how we use multiple nonverbal channels simultaneously to communicate.

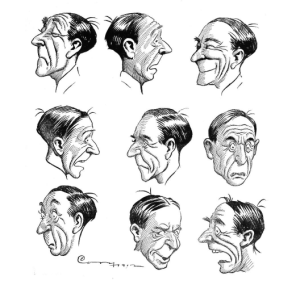

It can be difficult to decode a sender’s single verbal message due to the arbitrary, abstract, and ambiguous nature of language. But, think how much more difficult it is to decode the even more ambiguous and multiple nonverbal signals we take in like eye contact, facial expressions, body movements, clothing, personal artifacts, and tone of voice all at the same time. Despite this difficulty, Motley found that we learn to decode nonverbal communication as babies. Hall found that women are much better than men at accurately interpreting the many nonverbal cues we send and receive (Gore). How we interpret these nonverbal signals can also be influenced by our gender as the viewer.

A second difference between verbal and nonverbal communication is that verbal communication is distinct (linear) while nonverbal communication is continuous (in constant motion and relative to context). Distinct means that messages have a clear beginning and end, and are expressed in a linear fashion. We begin and end words and sentences in a linear way to make it easier for others to follow and understand. If you pronounce the word “cat” you begin with the letter “C” and proceed to finish with “T.” Continuous means that messages are ongoing and work in relation to other nonverbal and verbal cues. Think about the difference between analog and digital clocks. The analog clock represents nonverbal communication in that we generate meaning by considering the relationship of the different arms to each another (context). Also, the clock’s arms are in continuous motion. We notice the speed of their movement, their position in the circle and to each other, and their relationship with the environment (is it day or night?).

Nonverbal communication is similar in that we evaluate nonverbal cues in relation to one another and consider the context of the situation. Suppose you see your friend in the distance. She approaches, waves, smiles, and says “hello.” To interpret the meaning of this, you focus on the wave, smile, tone of voice, her approaching movement, and the verbal message. You might also consider the time of day, if there is a pressing need to get to class, etc.

Now contrast this to a digital clock, which functions like verbal communication. Unlike an analog clock, a digital clock is not in constant motion. Instead, it replaces one number with another to display time (its message). A digital clock uses one distinct channel (numbers) in a linear fashion. When we use verbal communication, we do so like the digital clock. We say one word at a time, in a linear fashion, to express meaning.

A third difference between verbal and nonverbal communication is that we use verbal communication consciously while we generally use nonverbal communication unconsciously. Conscious communication means that we think about our verbal communication before we communicate. Unconscious communication means that we do not think about every nonverbal message we communicate. If you ever heard the statement as a child, “Think before you speak” you were being told a fundamental principle of verbal communication. Realistically, it’s nearly impossible not to think before we speak. When we speak, we do so consciously and intentionally. In contrast, when something funny happens, you probably do not think, “Okay, I’m going to smile and laugh right now.” Instead, you react unconsciously, displaying your emotions through these nonverbal behaviors. Nonverbal communication can occur as unconscious reactions to situations. We are not claiming that all nonverbal communication is unconscious. At times we certainly make conscious choices to use or withhold nonverbal communication to share meaning. Angry drivers use many conscious nonverbal expressions to communicate to other drivers! In a job interview you are making conscious decisions about your wardrobe, posture, and eye contact.

A fourth difference between verbal and nonverbal communication is that some nonverbal communication is universal (Hall, Chia, and Wang; Tracy & Robins). Verbal communication is exclusive to the users of a particular language dialect, whereas some nonverbal communication is recognized across cultures. Although cultures most certainly have particular meanings and uses for nonverbal communication, there are universal nonverbal behaviors that almost everyone recognizes. For instance, people around the world recognize and use expressions such as smiles, frowns, and the pointing of a finger at an object. Note: Not all nonverbal gestures are universal! For example, if you travel to different regions of the world, find out what is appropriate! For example if you go to South Korea don’t offer payment with only one hand. For more examples, visit this webpage (link: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/galleries/Rude-hand-gestures-of-the-world/).

Let us sum up the ways in which nonverbal communication is unique:

- Nonverbal communication uses multiple channels simultaneously.

- Nonverbal communication is continuous.

- Nonverbal communication can be both conscious and unconscious.

- Certain nonverbal communication is universally understood.

Now that you have a definition of nonverbal communication, and can identify the primary differences between verbal and nonverbal communication, let’s examine the functions of nonverbal communication.

Functions of Nonverbal Communication

You learned that we use verbal communication to express ideas, emotions, experiences, thoughts, objects, and people. But what functions does nonverbal communication serve as we communicate (Blumer)? Even though it’s not through words, nonverbal communication serves many functions to help us communicate meanings with one another more effectively.

We use nonverbal communication to duplicate verbal communication. When we use nonverbal communication to duplicate, we use nonverbal communication that is recognizable to most people within a particular cultural group. Obvious examples include a head-nod or a head-shake to duplicate the verbal messages of “yes” or “no.” If someone asks if you want to go to a movie, you might verbally answer “yes” and at the same time nod your head. This accomplishes the goal of duplicating the verbal message with a nonverbal message. Interestingly, the head nod is considered a “nearly universal indication of accord, agreement, and understanding” because the same muscle in the head nod is the same one a baby uses to lower its head to accept milk from its mother’s breast (Givens). We witnessed a two year old girl who was learning the duplication function of nonverbal communication, and didn’t always get it right. When asked if she wanted something, her “yes” was shaking her head side to side as if she was communicating “no.” However, her “no” was the same head-shake but it was accompanied with the verbal response “no.” So, when she was two, she thought that the duplication was what made her answer “no.”

We use nonverbal communication to replace verbal communication. If someone asks you a question, instead of a verbal reply “yes” and a head-nod, you may choose to simply nod your head without the accompanying verbal message. When we replace verbal communication with nonverbal communication, we use nonverbal behaviors that are easily recognized by others such as a wave, head-nod, or head-shake. This is why it was so confusing for others to understand the young girl in the example above when she simply shook her head in response to a question. This was cleared up when someone asked her if she wanted something to eat and she shook her head. When she didn’t get food, she began to cry. This was the first clue that the replacing function of communication still needed to be learned. Consider how universal shaking the head side-to-side is as an indicator of disbelief, disapproval, and negation. This nonverbal act is used by human babies to refuse food or drink; rhesus monkeys, baboons, bonnet macaques and gorillas turn their faces sideways in aversion; and children born deaf/blind head shake to refuse objects or disapprove of touch (Givens).

We use nonverbal cues to complement verbal communication. If a friend tells you that she recently received a promotion and a pay raise, you can show your enthusiasm in a number of verbal and nonverbal ways. If you exclaim, “Wow, that’s great! I’m so happy for you!” while at the same time smiling and hugging your friend, you are using nonverbal communication to complement what you are saying. Unlike duplicating or replacing, nonverbal communication that complements cannot be used alone without the verbal message. If you simply smiled and hugged your friend without saying anything, the interpretation of that nonverbal communication would be more ambiguous than using it to complement your verbal message.

We use nonverbal communication to accent verbal communication. While nonverbal communication complements verbal communication, we also use it to accent verbal communication by emphasizing certain parts of the verbal message. For instance, you may be upset with a family member and state, “I’m very angry with you.” To accent this statement nonverbally you might say it, “I’m VERY angry with you,” placing your emphasis on the word “very” to demonstrate the magnitude of your anger. In this example, it is your tone of voice (paralanguage) that serves as the nonverbal communication that accents the message. Parents might tell their children to “come here.” If they point to the spot in front of them dramatically, they are accenting the “here” part of the verbal message.

We use nonverbal communication to regulate verbal communication. Generally, it is pretty easy for us to enter, maintain, and exit our interactions with others nonverbally. Rarely, if ever, would we approach a person and say, “I’m going to start a conversation with you now. Okay, let’s begin.” Instead, we might make eye contact, move closer to the person, or face the person directly — all nonverbal behaviors that indicate our desire to interact. Likewise, we do not generally end conversations by stating, “I’m done talking to you now” unless there is a breakdown in the communication process. We are generally proficient enacting nonverbal communication such as looking at our watch, looking in the direction we wish to go, or being silent to indicate an impending end in the conversation. When there is a breakdown in the nonverbal regulation of conversation, we may say something to the effect, “I really need to get going now.” In fact, we’ve seen one example where someone does not seem to pick up on the nonverbal cues about ending a phone conversation. Because of this inability to pick up on the nonverbal regulation cues, others have literally had to resort to saying, “Okay, I’m hanging up the phone right now” followed by actually hanging up the phone. In these instances, there was a breakdown in the use of nonverbal communication to regulate conversation.

We use nonverbal communication to contradict verbal communication. Imagine that you visit your boss’s office and she asks you how you’re enjoying a new work assignment. You may feel obligated to respond positively because it is your boss asking the question, even though you may not truly feel this way. However, your nonverbal communication may contradict your verbal message, indicating to your boss that you really do not enjoy the new work assignment. In this example, your nonverbal communication contradicts your verbal message and sends a mixed message to your boss. Research suggests that when verbal and nonverbal messages contradict one another, receivers often place greater value on the nonverbal communication as the more accurate message (Argyle, Alkema & Gilmour). One place this occurs frequently is in greeting sequences. You might say to your friend in passing, “How are you?” She might say, “Fine” but have a sad tone to her voice. In this case, her nonverbal behaviors go against her verbal response. We are more likely to interpret the nonverbal communication in this situation than the verbal response.

We use nonverbal communication to mislead others. We can also use nonverbal communication to deceive, and often, focus on a person’s nonverbal communication when trying to detect deception. Recall a time when someone asked your opinion of a new haircut. If you did not like it, you may have stated verbally that you liked the haircut and provided nonverbal communication to further mislead the person about how you really felt. Conversely, when we try to determine if someone is misleading us, we generally focus on the nonverbal communication of the other person. One study suggests that when we only use nonverbal communication to detect deception in others, 78% of lies and truths can be detected (Vrij, Edward, Roberts, & Bull). However, other studies indicate that we are really not very effective at determining deceit in other people (Levine, Feeley & McCornack), and that we are only accurate 45 to 70 percent of the time when trying to determine if someone is misleading us (Kalbfleisch; Burgoon, et al.; Horchak, Giger, Pochwatko). When trying to detect deception, it is more effective to examine both verbal and nonverbal communication to see if they are consistent (Vrij, Akehurst, Soukara, & Bull). Even further than this, Park, Levine, McCornack, Morrison, & Ferrara argue that people usually go beyond verbal and nonverbal communication and consider what outsiders say, physical evidence, and the relationship over a longer period of time. Read further in this body language article if you want to learn more about body language and how to detect lies (link: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/Body_Language.htm).

We use nonverbal communication to indicate relational standing(Mehrabian; Burgoon, Buller, Hale, & deTurck; Le Poire, Duggan, Shepard, & Burgoon; Sallinen-Kuparinen; Floyd & Erbert). Take a few moments today to observe the nonverbal communication of people you see in public areas. What can you determine about their relational standing from their nonverbal communication? For example, romantic partners tend to stand close to one another and touch one another frequently. On the other hand, acquaintances generally maintain greater distances and touch less than romantic partners. Those who hold higher social status often use more space when they interact with others. In the United States, it is generally acceptable for women in platonic relationships to embrace and be physically close while males are often discouraged from doing so. Contrast this to many other nations where it is custom for males to greet each other with a kiss or a hug and hold hands as a symbol of friendship. We make many inferences about relational standing based on the nonverbal communication of those with whom we interact and observe. Imagine seeing a couple talking to each other across a small table. They both have faces that look upset, red eyes from crying, closed body positions, are leaning into each other, and are whispering emphatically. Upon seeing this, would you think they were having a “Breakup conversation”?

We use nonverbal communication to demonstrate and maintain cultural norms. We’ve already shown that some nonverbal communication is universal, but the majority of nonverbal communication is culturally specific. For example, in United States culture, people typically place high value on their personal space. In the United States people maintain far greater personal space than those in many other cultures. If you go to New York City, you might observe that any time someone accidentally touches you on the subway he/she might apologize profusely for the violation of personal space. Cultural norms of anxiety and fear surrounding issues of crime and terrorism appear to cause people to be more sensitive to others in public spaces, highlighting the importance of culture and context.

If you go grocery shopping in China as a westerner, you might be shocked that shoppers would ram their shopping carts into others’ carts when they wanted to move around them in the aisle. This is not an indication of rudeness, but a cultural difference in the negotiation of space. You would need to adapt to using this new approach to personal space, even though it carries a much different meaning in the U.S. Nonverbal cues such as touch, eye contact, facial expressions, and gestures are culturally specific and reflect and maintain the values and norms of the cultures in which they are used.

We use nonverbal communication to communicate emotions. While we can certainly tell people how we feel, we more frequently use nonverbal communication to express our emotions. Conversely, we tend to interpret emotions by examining nonverbal communication. For example, a friend may be feeling sad one day and it is probably easy to tell this by her nonverbal communication. Not only may she be less talkative but her shoulders may be slumped and she may not smile. One study suggests that it is important to use and interpret nonverbal communication for emotional expression, and ultimately relational attachment and satisfaction (Schachner, Shaver, & Mikulincer). Research also underscores the fact that people in close relationships have an easier time reading the nonverbal communication of emotion of their relational partners than those who aren’t close. Likewise, those in close relationships can more often detect concealed emotions (Sternglanz & Depaulo).

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION SUMMARY

You have learned that we define nonverbal communication as any meaning shared through sounds, behaviors, and artifacts other than words. Some of the differences between verbal and nonverbal communication include the fact that verbal communication uses one channel while nonverbal communication occurs through multiple channels simultaneously. As a result, verbal communication is distinct while nonverbal communication is continuous. For the most part, nonverbal communication is enacted at an unconscious level while we are almost always conscious of our verbal communication. Finally, some nonverbal communication is considered universal and recognizable by people all over the world, while verbal communication is exclusive to particular languages.

REFERENCES

Argyle, Michael F., Alkema, Florisse, & Gilmour, Robin. “The communication of friendly and hostile attitudes: Verbal and nonverbal signals.” European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 385-402: 1971.

Blumer, Herbert. Symbolic interaction: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs; NJ: Prentice Hall. 1969.

Buck, Ross., & VanLear, Arthur. “Verbal and nonverbal communication: Distinguishing symbolic, spontaneous, and pseudo-spontaneous nonverbal behavior.” Journal of Communication, 52(3), 522-539: 2002.

Burgoon, Judee, et al. “Patterns Of Nonverbal Behavior Associated With Truth And Deception: Illustrations From Three Experiments.” Journal Of Nonverbal Behavior 38.3 (2014): 325-354. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

Burgoon, Judee K., Buller, David B., Hale, Jerold L., & deTurck, M.A. “Relational Messages Associated With Nonverbal Behaviors.” Human Communication Research, 10, 351-378: 1984.

Burgoon, Judee K., Buller, David B., & Woodall, W. Gill. Nonverbal communication: The unspoken dialogue. New York: Harper & Row: 1996.

Floyd, Kory, and Larry A. Erbert. “Relational Message Interpretations Of Nonverbal Matching Behavior: An Application Of The Social Meaning Model.” Journal Of Social Psychology 143.5: 581-597: 2003.

Givens, David B. Head-nod, [Webpage]. Center for Nonverbal Studies. 2000. Available: http://web.archive.org/20011029115903/members.aol.com/nonverbal3/headnod.htm [2006, April 20th].

Givens, David B. (2000). Head-shake, [Webpage]. Center for Nonverbal Studies. 2000. [2006, April 20th].

Gore, Jonathan. “The Interaction Of Sex, Verbal, And Nonverbal Cues In Same-Sex First Encounters.” Journal Of Nonverbal Behavior33.4 (2009): 279-299. Communication & Mass Media Complete.

Hall, Cathy W., Chia, Rosina, & Wang, Deng F. “Nonverbal communication among American and Chinese students.”Psychological Reports, 79, 419-428. 1996.

Hall, Edward T. Beyond culture. New York: Doubleday. 1959.

Hall, Edward T. The hidden dimension. New York: Doubleday. 1966.

Hall, Judith A. Nonverbal sex differences: Communication accuracy and expressive style. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1984.

Horchak Oleksandr V, Jean-Chrisophe Giger, and Grzegorz Pochwatko. “Simulation of Metaphorical Actions and Discourse Comprehension.” Metaphor and Symbol, 29.1 (2014): 1-22.

Kalbfleisch, Pamela. “Deceit, Distrust, and Social Milieu: Applications of deception research in a troubled world.” Journal of Applied Communication Research, 308-334. 1992.

Le Poire, Beth, Ashley Duggan, Carolyn Shepard, and Judee Burgoon. Relational Messages Associated with Nonverbal Involvement, Pleasantness, and Expressiveness in Romantic Couples. Taylor & Francis. Taylor & Francis Online, 06 June 2009.

Levine, Robert. A Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist, or How Every Culture Keeps Time Just a Little Bit Differently. New York: BasicBooks, 1997. Print

Levine, Timothy, Thomas Feeley, and Steven McCornack. “Testing the Effects of Nonverbal Behavior Training on Accuracy in Deception Detection with the Inclusion of a Bogus Training Control Group.” Western Journal of Communication, 69.3 : 203-217: 2005.

Mead, George. H. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1934) Print.

Mehrabian, Alabert. Silent Messages: Implicit Communication of Emotion and Attitudes (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. (1981) Print.

Motley, Mark. T. “Facial Affect and Verbal Context in Conversation: Facial Expression as Interjection.” Human Communication Research, 20 (1), 3-40 (1993) Print.

Park, Hee Sun., Levine, Timothy. R., McCornack, Steven. A., Morrison, Kelly., & Ferrara, Merrissa. “How People Really Detect Lies.” Communication Monographs,69(2), 144-157. 2002: Print.

Sallinen-Kuparinen, Aino. “Teacher Communicator Style.” Communication Education, 41, 153-166. 1992. Print.

Schachner, Dory., Shaver, Philip., & Mikulincer, Mmario. “Patterns of Nonverbal Behavior and Sensitivity in the Context of Attachment Relationships.” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 29(3), 141-169. 2005.

Sternglanz, R. Weylin., & Depaulo, Bella. M. “Reading Nonverbal Cues to Emotion: The Advantages and Reliabilities of Relationship Closeness.” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28(4), 245-266. 2004.

Tracy, Jessica L., and Richard W. Robins. “The Nonverbal Expression Of Pride: Evidence For Cross-Cultural Recognition.”Journal Of Personality & Social Psychology 94.3 (2008): 516-530. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

Vrij, Aldert., Akehurst, Lucy., Soukara, Stavroula., & Bull, Ray. “Detecting Deceit via Analyses of Verbal and Nonverbal Behavior in Children and Adults.” Human Communication Research, 30(1), 8-41. 2004.

Vrij, Aladert., Edward, Katherine., Roberts, Kim., & Bull, Ray. “Detecting Deceit via Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Behavior.” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 24(4), 239-263. 2000.

Nonverbal Communication is adapted from Process of Communication An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons. Authored and compiled by Tammera Stokes Rice licensed under CC BY 4.0.