11 Sensory Perception: Seizure, Epilepsy and Antiseizures, Antiepileptics ; Parkinson’s Disease and Antiparkinsons Drugs; Maladaptive Behavior and Psychopharmacology

This Chapter provides a basic introduction to the concepts of the central nervous system (CNS), cognition, mood, affect, and anxiety related to pharmacology. Cognition is “the process of thought that embodies perception, attention, visuospatial cognition, language, learning, memory, and executive function with the higher-order thinking skills of comprehension, insight, problem-solving, reasoning, decision making, creativity, and metacognition.”

Learning Objectives

- Understand the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of nerve disorders and spasticity.

- Explain the mechanism of action, indication for use, adverse effects, and the nursing process implications for dopaminergic agents, anticholinergic agents, antispasmodics, barbiturates, hydantoins, iminostilbenes, and miscellaneous antiepileptic agents.

- Explain the basic process of neurotransmission and synaptic transmission of psychiatric medications for anxiety and depression.

- Describe the mechanism of action, indication of use, and adverse effects of benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and atypical antidepressant agents.

- Apply the nursing process implications for the safe administration of medications for a patient taking psychopharmacology medications.

I. CNS Regulation, Mood, and Cognition Concepts

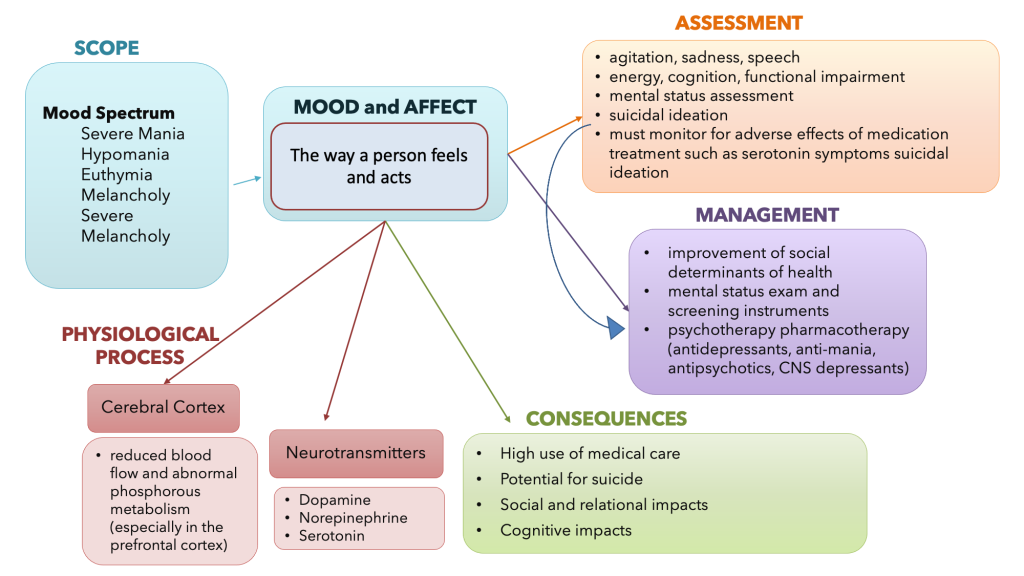

The concept map below summarizes mood, affect, and CNS information. You are encouraged to revisit this map after you have completed the chapter. In this chapter, you may also wish to develop your own concept map related to other CNS concepts.

Mood and Affect Concept Map

Overview of the Central Nervous System and Processes

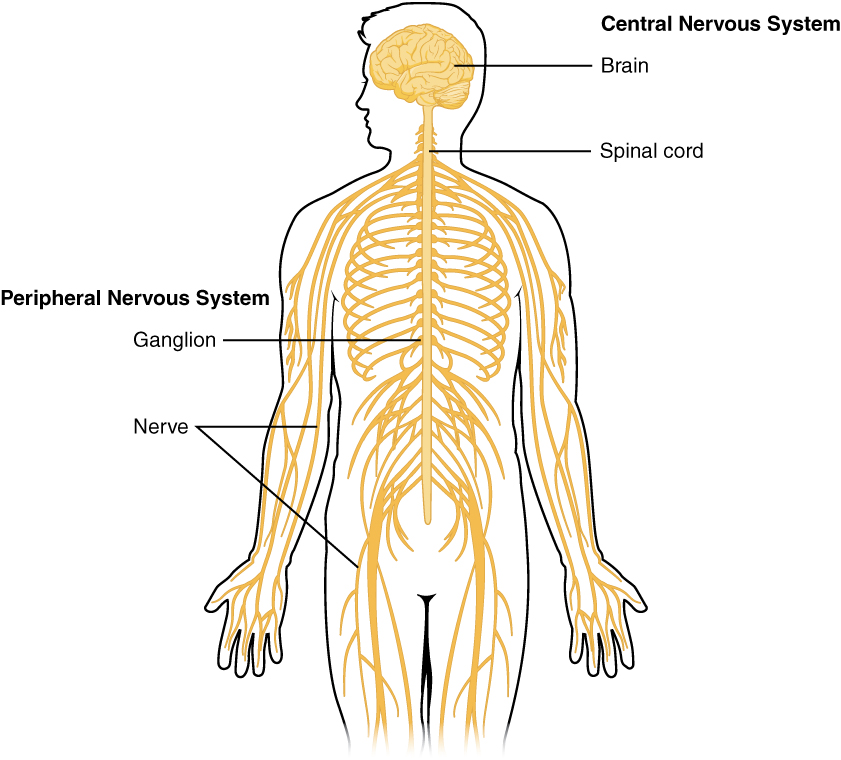

Before we can begin to understand how different medications influence the brain, we need to review the central nervous system. The nervous system can be divided into two major regions: the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) is the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is everything else. The brain is contained within the cranial cavity of the skull, and the spinal cord is within the vertebral cavity of the vertebral column.

It is a bit of an oversimplification to say that the CNS is inside these two cavities and the peripheral nervous system is outside of them, but that is one way to start to think about it. In actuality, some elements of the peripheral nervous system are within the cranial or vertebral cavities. The peripheral nervous system is so named because it is on the periphery—meaning beyond the brain and spinal cord. Depending on different aspects of the nervous system, the dividing line between central and peripheral is not necessarily universal.

The Central and Peripheral Nervous System

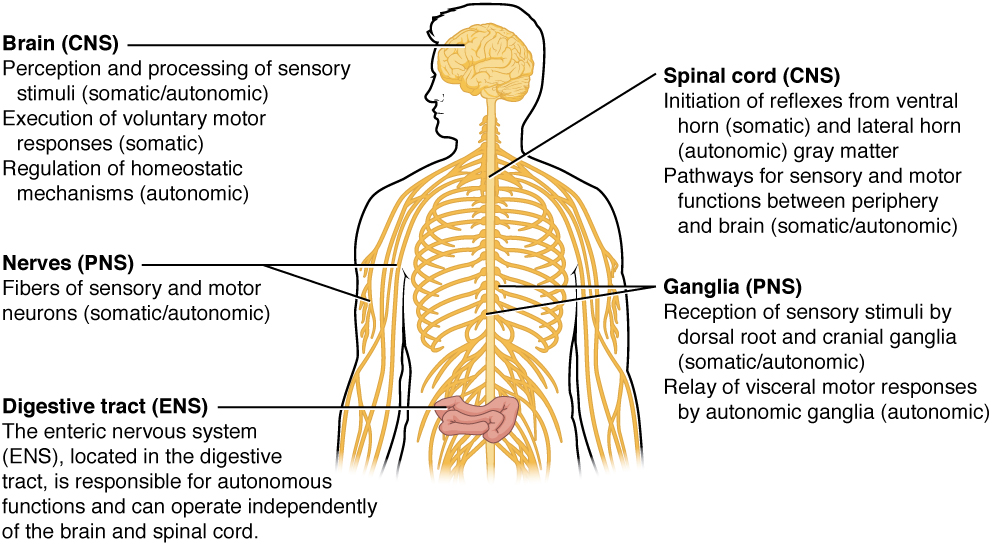

Somatic, Autonomic, and Enteric Structures of the Nervous System

Review more detailed information about the nervous system function using this OpenStax link: Basic structure and function of the nervous system

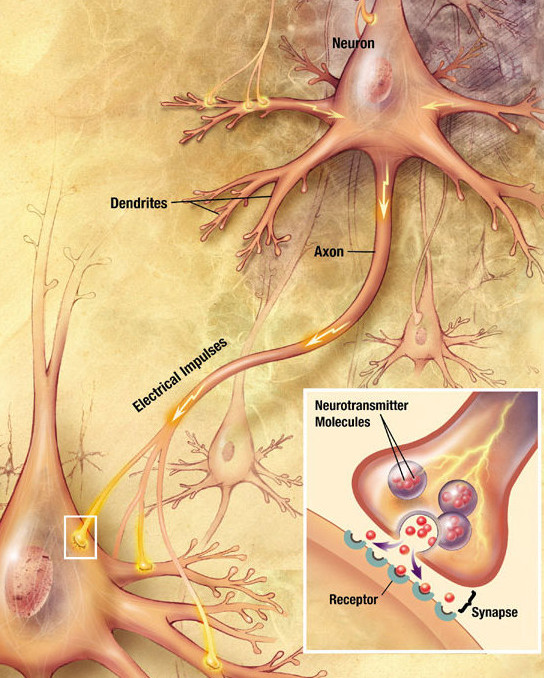

Communication in the Nervous System

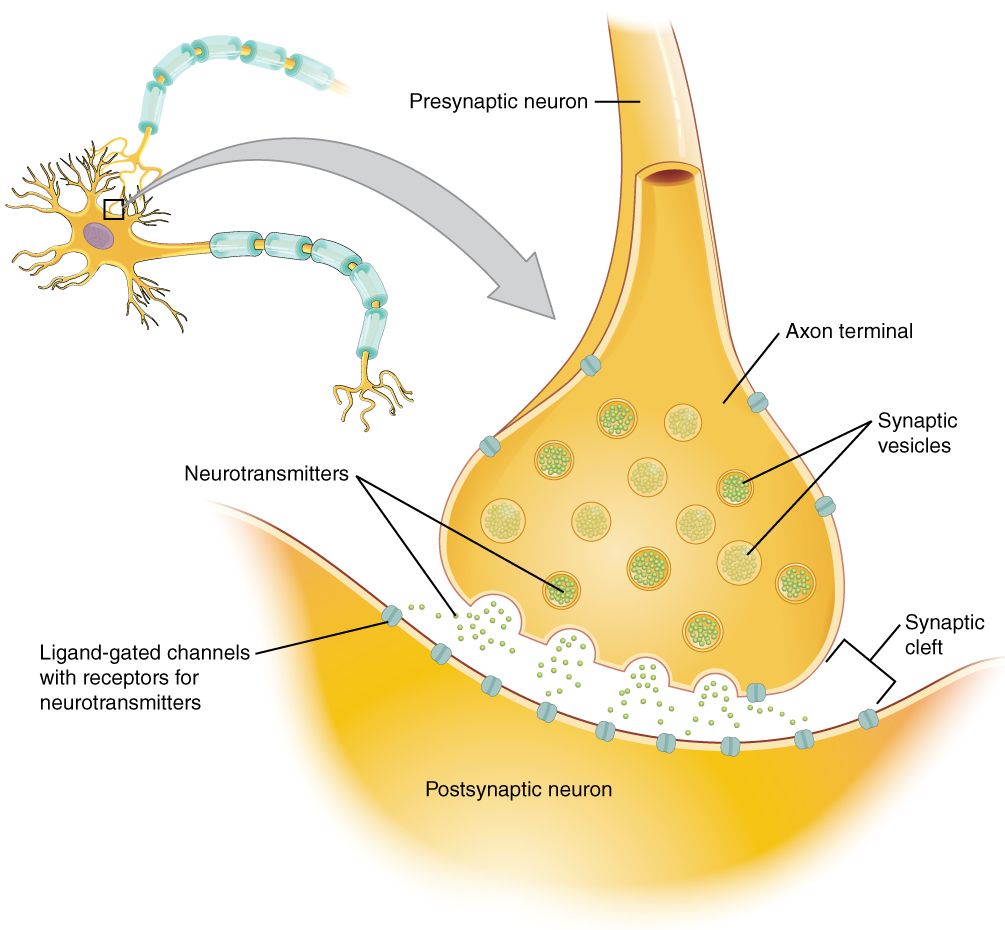

Your brain communicates with electrical impulses that signal a neurotransmitter release, which then binds to the targeted cell. Understanding this communication will help you put the pieces together when trying to understand the medication’s mechanism of action that influences neurotransmitters. See below for an illustration of the major elements in neuron communication.

Major Elements in Neuron Communication

There are two types of connections between electrically active cells: chemical synapses and electrical synapses. In a chemical synapse, a chemical signal—a neurotransmitter—is released from one cell and affects another. In comparison, in an electrical synapse, there is a direct connection between the two cells so that ions can pass directly from one cell to the next. In this unit, we will focus on the communication of a neurotransmitter in a chemical synapse. Once in the synaptic cleft, the neurotransmitter diffuses a short distance to the postsynaptic membrane and can interact with neurotransmitter receptors. Receptors are specific for neurotransmitters; the two fit together like a key and lock. One neurotransmitter binds to its receptor and will not bind to receptors for other neurotransmitters, making the binding a specific chemical event.

Major Elements in Neuron Communication

When the neurotransmitter binds to the receptor, the cell membrane of the target neuron changes its electrical state, and a new graded potential begins. The second neuron generates an action potential if that graded potential is strong enough to reach the threshold. The target of this neuron is another neuron in the thalamus of the brain, the part of the CNS that acts as a relay for sensory information. The thalamus sends the sensory information to the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of gray matter in the brain, where conscious perception of that stimulus begins.

Neuron Action Potential

Types of Neurotransmitters

Amino Acids

One group of neurotransmitters is amino acids. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is an example of an amino acid neurotransmitter. They each have their own receptors and do not interact with each other. Amino acid neurotransmitters are eliminated from the synapse by reuptake. A pump in the cell membrane of the presynaptic element, or sometimes a neighboring glial cell, will clear the amino acid from the synaptic cleft so that it can be recycled, repackaged in vesicles, and released again.

Biogenic Amine

Another class of neurotransmitters is the biogenic amine, which is enzymatically made from amino acids. For example, serotonin is made from tryptophan. It is the basis of the serotonergic system, which has its own specific receptors. Serotonin is transported back into the presynaptic cell for repackaging.

Other biogenic amines are made from tyrosine and include dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Dopamine is part of its own system, the dopaminergic system, which has dopamine receptors. Norepinephrine and epinephrine belong to the adrenergic neurotransmitter system. The two molecules are very similar and bind to the same receptors, which are referred to as alpha- and beta-receptors. The biogenic amines have mixed effects. For example, dopamine receptors that are classified as D1 receptors are excitatory, whereas D2-type receptors are inhibitory.

The important thing to remember about neurotransmitters and signaling chemicals is that the effect is entirely dependent on the receptor.

Functions of Neurotransmitters

An alteration in CNS function is related to abnormal impulse transmission and can result in an imbalance of a neurotransmitter. A person with an imbalance of neurotransmitters may have signs and symptoms of a CNS disorder. The medications that are used to treat CNS disorders mimic or block the neurotransmitter based on the imbalance caused by the condition. Medications are used to either stimulate or depress the effect of the neurotransmitter. For example, CNS depressants alter the brain by decreasing the excitability of neurotransmitters, blocking their receptor site, or increasing the inhibitory neurotransmitter. On the other hand, CNS stimulants increase brain activity by increasing the excitability of neurotransmitters, decreasing the inhibitory neurotransmitters, or blocking their receptor sites.

Norepinephrine is often associated with the fight-or-flight response. Abnormal levels of this neurotransmitter are also associated with depression, decreased alertness, and interest, along with possible palpitations, anxiety, and panic attacks. Dopamine is strongly linked to motor and cognition. This neurotransmitter influences movement and can be associated with ADHD, paranoia, and schizophrenia. Serotonin is heavily involved in many bodily processes. Abnormal levels of serotonin can affect sleep, libido, mood, and temperature regulation. Alterations of this neurotransmitter have been linked to many mental health issues, such as depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and body disorders. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) can act as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. GABA assists with communication in the brain, and if this neurotransmitter is low, it has been linked to issues such as anxiety, seizures, mania, and impulse control. The neurotransmitter glutamate works as an excitatory neurotransmitter and works with GABA to control other functions of the brain.

Mood and affect – the way a person feels and acts.

Scope – mood spectrum:

- severe mania

- hypomania

- euthymia

- melancholy

- severe melancholy

Physiological process:

- Cerebral cortex

- reduced blood flow and abnormal phosphorous metabolism (especially in the prefrontal cortex)

- Neurotransmitters

- dopamine

- norepinephrine

- serotonin

Assessment:

- agitation, sadness, speech

- energy, cognition, functional impairment

- mental status assessment

- suicidal ideation

- must monitor for adverse effects of medication treatment such as serotonin symptoms and suicidal ideation

Management:

- improvement of social determinants of health

- mental status exam and screening instruments

- psychotherapy pharmacotherapy (anti-depressants, anti-mania, antipsychotics, CNS depressants).

Consequences:

- high use of medical care

- potential for suicide

- social and relational impacts

- cognitive impacts

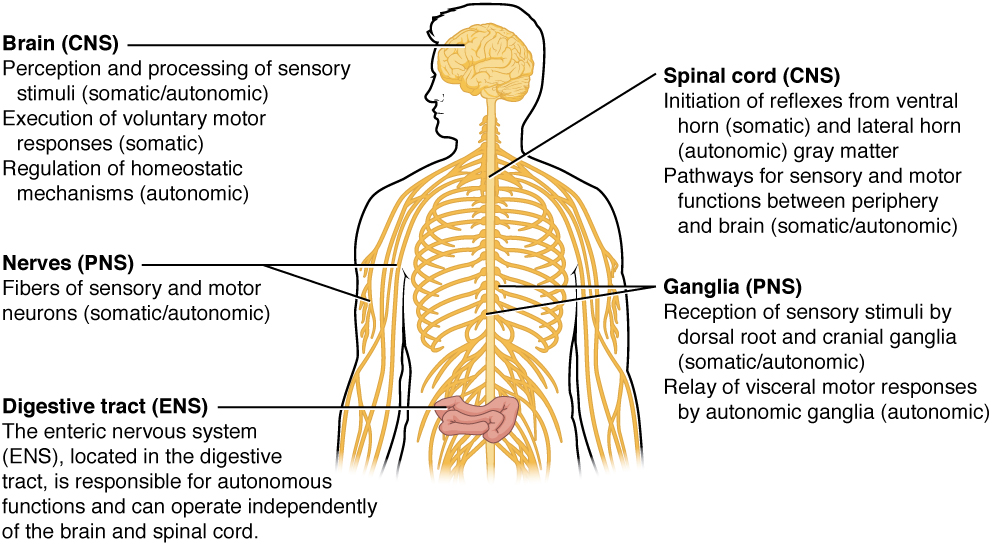

Somatic, Autonomic, and Enteric Structures of the Nervous System

Brain (CNS)

- perception and processing of sensory stimuli (somatic/autonomic)

- execution of voluntary motor responses (somatic)

- regulation of homeostatic mechanisms (autonomic)

Spinal cord (CNS)

- initiation of reflexes from ventral horn (somatic) and lateral horn (autonomic) gray matter

- pathways for sensory and motor functions between the periphery and brain (somatic/autonomic)

Nerve (PNS)

- fibers of sensory and motor neurons (somatic/autonomic)

Ganglia (PNS)

- reception of sensory stimuli by dorsal root and cranial ganglia (somatic/autonomic)

- relay of visceral motor responses by autonomic ganglia (autonomic)

Digestive tract (ENS)

- the enteric nervous system (ENS), located in the digestive tract, is responsible for autonomous functions and can operate independently of the brain and spinal cord.

Diseases and Disorders of the CNS, Mood, and Cognition

Now that we have reviewed the basic concepts of neurotransmitters and their function let’s review common conditions and diseases related to the central nervous system, cognition, and mood, including anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, ADHD, seizures, and Parkinson’s.

Additional supplementary videos about CNS disorders are available at Khan Academy

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders are a group of conditions marked by pathological or extreme anxiety or dread. People with anxiety experience disturbances of mood, behavior, and most systems in the body, making them unable to continue with everyday activities. Many feel anxious most of the time for no apparent reason.

Anxiety is different from fear. Fear is a person’s response to an event or object. The psychiatric disorder of anxiety occurs when the intensity and duration of anxiety do not match the potential for harm or threat to the affected person. Anxiety can be expressed with physical symptoms or behaviorally.

Signs and Symptoms of Anxiety

- Aches

- Pains

- Stomach aches

- Headaches

- Heart racing or pounding

- Trembling

- Sweating

- Difficulty concentrating (see Figure 9.3a)

- Increased agitation

- Crying

Many patients with anxiety experience difficulty concentrating

Treatment can include non-pharmacological interventions as well as medications. Non-pharmacological interventions to decrease anxiety include relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, exercise, psychotherapy, support groups, or cognitive behavioral therapy. Anti-anxiety medications can also be used to help both verbal and nonverbal patients feel a much-needed sense of peace.

Learn more about anxiety from the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Depression

Depression is a frequent problem, affecting up to 5% of the population. To be diagnosed with depression, five of the following symptoms must be present during the same two-week period and represent a change from previous functioning. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The symptoms of depression cannot be due to the effects of a substance or from grief.

Signs and Symptoms of Depression

- Depressed mood

- Diminished interest

- Weight loss when not dieting or weight gain

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Agitation

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feeling of worthlessness

- Inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to concentrate

- Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempt

Treatment of depression may include medication, psychotherapy, cognitive therapy, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and group therapy. Patients who are depressed may not report symptoms unless specifically asked, and they may be suicidal. Using assessment techniques to gather information about the history of each patient’s depression, support system, specific triggering events, psychosocial assessment, and risk for harm to self or others is imperative. Each patient’s response to medication is unpredictable, and often, medications will need to be adjusted based on reported symptoms.

Learn more about depression from the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Bipolar

Serious mood swings mark bipolar affective disorder. Typically, patients experience extreme highs (called mania or hypomania) alternating with extreme lows (depression). See the “Depression” section for signs and symptoms of depression. People feel normal only in the periods between the highs and lows. For some people, the cycles occur so rapidly that they hardly ever feel a sense of control over their mood swings.

Signs and Symptoms of a Manic Episode

- Rapid speech

- Hyperactivity

- Reduced need for sleep

- Flight of ideas

- Grandiosity

- Poor judgment

- Aggression/hostility

- Risky sexual behavior

- Neglect basic self-care

- Decreased impulse control

Treatment for a patient diagnosed with bipolar may include medication, safety initiatives during acute mania, ECT, psychotherapy, and support groups. The severity of manic and depressive episodes varies for each patient. The priority is assessing if a patient is a danger to others or themselves. People with bipolar may need assistance with impulse control during times when they are in a manic state.

Learn more about bipolar disorder from the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia affects people from all walks of life and usually first appears between the ages of 15 and 30. Not everyone will experience the same symptoms, but many symptoms are common, such as withdrawing, hearing voices, talking to oneself, seeing things that are not there, neglecting personal hygiene, and showing low energy.

Schizophrenia refers to a group of severe, disabling psychiatric disorders marked by withdrawal from reality, illogical thinking, delusions (fixed false beliefs that cannot be changed through reasoning), hallucinations (hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, or feeling touched by things that are not there), and flat affect (lack of observable expressions of emotions, monotone voice, expressionless face, immobile body).

Signs and Symptoms of Schizophrenia

There are three types of symptoms related to schizophrenia: positive, negative, and cognitive.

Positive Symptoms

Note that in this context, the word positive is not the same as good. Rather, positive symptoms are psychotic and demonstrate how the individual has lost touch with reality. Positive symptoms include:

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized thinking and behavior

Delusions fall into several categories. Individuals with a persecutory delusion may believe they are being tormented, followed, tricked, or spied on. Individuals with a grandiose delusion may believe they have special powers. Individuals with a reference delusion may believe that passages in books, newspapers, television shows, song lyrics, or other environmental cues are directed toward them. In delusions of thought withdrawal or thought insertion, individuals believe others are reading their mind, their thoughts are being transmitted to others, or outside forces are imposing their thoughts or impulses on them.

Hallucinations may include hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, or feeling as if they have been touched by things that are not there.

Negative Symptoms

Negative symptoms are those characteristics that should be there but are lacking. Negative symptoms include:

- Apathy (lack of interest in people, things, activities)

- Lack of motivation

- Blunted affect

- Poverty of speech (brief replies)

- Anhedonia (lack of interest in activities once enjoyed)

- Avoidance of relationships

Keep in mind that the inability to show emotion associated with a blunted affect does not reflect an inability to feel emotion. Similarly, it is helpful to understand that withdrawing from others is a coping mechanism for an individual with schizophrenia and not a rejection of those who initiate contact.

Cognitive

Cognitive symptoms are a change in thought patterns and include:

- Poor decision making

- Loss of memory

- Distracted

- Difficulty focusing

Treatment for a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia may include medications to control positive and/or negative signs and symptoms and nonpharmacological interventions such as limit setting, therapeutic communication, ECT, and psychotherapy. Key assessments for a patient with schizophrenia include examination for hallucinations and delusions, use of additional substances (alcohol or drugs), safety, support system, and a medication review with a focus on compliance with their therapeutic regimen.

Learn more about schizophrenia from the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by hyperactivity, lack of impulse control, and/or lack of attention that interferes with how a person functions. ADHD is often diagnosed during childhood, but signs and symptoms can last through adulthood.

Signs and Symptoms of ADHD

- Hyperactivity

- Inability to concentrate

- Difficulty with self-control

- Lack of emotional control

A child with ADHD may have difficulty sitting still and focusing at school or have emotional outbursts. These behaviors often impact their life. Medication, psychotherapy, behavior management, and family support all play a large part in helping an individual with ADHD. Additional resources for parents are also helpful.

Patients with ADHD may have difficulty in focusing on details

Learn more about ADHD from Canada’s Center for Addiction and Mental Health.

Seizures

The official definition of a seizure is “a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to an abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.” This means that during a seizure, large numbers of brain cells are activated abnormally at the same time. It is like an electrical storm in the brain. They may alter consciousness and produce abnormal motor activity. There are different classifications of seizures based on the severity of symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms of Seizures

Motor Symptoms

- Jerking (clonic)

- Muscles becoming limp or weak (atonic)

- Tense or rigid muscles (tonic)

- Brief muscle twitching (myoclonus)

- Epileptic spasms

Non-motor Symptoms

- Changes in sensation, emotions, thinking, or autonomic functions

- Lack of movement

Classification of Seizures

Seizures are classified in many ways, beginning with whether they are partial or generalized seizures.

Partial Seizures

Partial seizures have a focal onset on one side of the brain. They are further classified into simple, complex, or secondarily generalized:

- Simple partial seizures are the most common. They may also affect sensory and autonomic systems.

- Complex partial seizures include impairment of consciousness, with or without motor activity or other signs.

- Simple or complex partial seizures may become secondarily generalized, producing a tonic-clonic seizure.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures have bilateral onset on both sides of the brain. They are typified by petit mal seizures, which can be recognized by clinical characteristics as well as interictal EEG abnormalities.

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus is a state of repeated or continuous seizures. It is often defined operationally as a single seizure lasting more than 20 minutes or repeated seizures without recovery of consciousness. Prolonged status epilepticus leads to irreversible brain injury and has a very high rate of mortality. The goal of therapy should be to achieve control of a seizure within 60 minutes or less. Pharmacological treatment of seizures is very successful in the majority of cases, but it requires accurate diagnosis and classification of seizures. Medication management of seizures may include CNS depressants, benzodiazepines or barbiturates, or anticonvulsants such as phenytoin.

Parkinson’s Disease

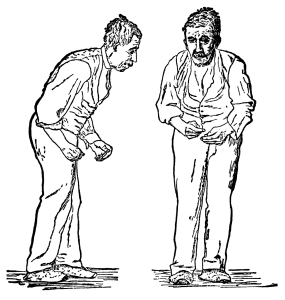

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disease of the nervous system that impairs one’s ability to move. The typical onset of Parkinson’s disease is middle to later stages of life. This disease worsens over time and has no cure. The cause of this disease is unknown, but it is known that a loss of dopaminergic neurons characterizes it.

Signs and Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

- Tremor at rest

- Bradykinesia

- Muscle rigidity

- Postural instability

- Gait disturbance

- Dystonia

- Ophthalmoplegia

- Active mood disorders

See below for a typical posture associated with Parkinson’s disease. Treatment for a patient with Parkinson’s disease often includes medication to increase dopamine in the brain to slow the progression of the disease.

The typical stooping posture associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Potential new treatment of proteins in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease

The underlying cause of some neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, appears to be related to proteins—specifically, to proteins behaving badly. One of the strongest theories of what causes Alzheimer’s disease is based on the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, dense conglomerations of a protein that is not functioning correctly. Parkinson’s disease is linked to an increase in a protein known as alpha-synuclein that is toxic to the cells of the substantia nigra nucleus in the midbrain.

For proteins to function correctly, they are dependent on their three-dimensional shape. The linear sequence of amino acids folds into a three-dimensional shape that is based on the interactions between and among those amino acids. When the folding is disturbed, and proteins take on a different shape, they stop functioning correctly. However, the disease is not necessarily the result of functional loss of these proteins; rather, these altered proteins start to accumulate and may become toxic. For example, in Alzheimer’s, the hallmark of the disease is the accumulation of these amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex. The term coined to describe this sort of disease is “proteopathy,” and it includes other diseases. Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, the human variant of the disease known as mad cow disease, also involves the accumulation of amyloid plaques, similar to Alzheimer’s. Diseases of other organ systems can fall into this group as well, such as cystic fibrosis or type 2 diabetes. Recognizing the relationship between these diseases has suggested new therapeutic possibilities. Interfering with the accumulation of the proteins, possibly as early as their original production within the cell, may unlock new ways to alleviate these devastating diseases.

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making for CNS Regulation, Mood, and Cognition

Clinical reasoning is how nurses think and process our knowledge, including what we have read or learned in the past, and apply it to the current practice context of what we see. Nurses make decisions all the time, but making decisions requires a complex thinking process. Many tools are useful and can be found online to support your thinking through clinical judgments. This book uses the nursing process and clinical judgment language to help you understand the application of medication to your clinical practice.

Now that we have reviewed various CNS disorders and their anatomy and physiology let’s review the importance of the nursing process and clinical judgment in guiding the nurse who administers CNS medication to treat these disorders.

Assessment

Although there are numerous details to consider when administering medications, it is always important to first think about what you are giving and why.

First, let’s think of why. Recognizing Cues

When thinking about administering CNS medication, there are many things to consider. Each medication is given for a specific purpose for your patient, and it is your job as a nurse to assess your patients and collect important data before safely administering medication. As a nurse, not only will you perform the skill of administering medications, but you will be expected to think critically about your patient and the safety of any medication at any particular time.

A nursing assessment completed prior to administering CNS medication will likely look different than an assessment for other types of medication because most of the assessments associated with CNS medication are done by collecting subjective data rather than objective data. For example, prior to administering a cardiac medication, a nurse will obtain objective data such as blood pressure and an apical heart rate. However, prior to administering CNS medication, a nurse will use therapeutic communication to ask questions to gather subjective data about how the patient is feeling.

After reviewing the possible diseases connected with the CNS system, you probably noticed that there is usually an associated imbalance of a neurotransmitter. As a nurse, you cannot directly measure a neurotransmitter to determine the effects of the medication, but you can ask questions to determine how your patient is feeling emotionally and perceiving the world, conditions that are influenced by neurotransmitter levels. An example of a nurse using therapeutic communication to perform subjective assessment is asking a question such as, “Tell me more about how you are feeling today?” The nurse may also use general survey techniques such as simply observing the patient to assess for cues of behavior. Examples of data collected by a general survey could be assessing the patient’s mood, hygiene, appearance, or movement.

Interventions

Next, plan (refine your hypothesis), and take action.

With the administration of any medication, it is important to always perform the five rights (right patient, medication, dose, route, and time) and to check for allergies before administration. It is important to anticipate any common side effects and the expected outcome of the medication. When you administer CNS medication, it is key to perform assessments before administering medication because many patients may have changing behaviors and habits that influence the way they think and feel about taking their medication. Additionally, some medications require an assessment of lab values before administration. Many CNS medications may also have cumulative effects when used in conjunction with other medications, so careful assessment of the impact of the medications on one another is needed.

Evaluation

Finally, evaluate the outcomes of your action.

It is important always to evaluate the patient’s response to a medication. Some CNS medications will take weeks to become therapeutic for the patient. It is key to teach the patient about when the medication is expected to produce an effect. Nurses should assess for mood, behavior, and movement improvement. If medications are effective, patients should report fewer negative thoughts, worry, and symptomatic behaviors and demonstrate fewer abnormal movements. Nurses also need to continually monitor for adverse effects, some of which can be life-threatening and require prompt notification to the prescribing provider.

Additionally, if symptoms are not improving or the patient’s condition worsens, the nurse should promptly notify the prescribing provider for further orders. For example, a symptom and/or adverse reaction of several CNS medications is increased thoughts of suicide. If a patient is experiencing thoughts of suicide, immediate assistance should be obtained to keep them safe. For more information about suicide prevention, refer to the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention site.

Now that we have reviewed CNS basics and how to use the nursing process related to CNS medications, we will take a closer look at specific classes of CNS medications. We will review classes and specific administration considerations, therapeutic effects, adverse/side effects, and teaching needed for each class of medications.

CNS Depressants

CNS depressants can slow brain activity, making them useful for conditions related to seizures and anxiety. Barbiturates and benzodiazepines are examples of CNS depressants.

Barbiturates

Phenobarbital is an example of a barbiturate primarily used as a sedative and to treat seizure disorders. In high doses, it can be used to induce anesthesia, and overdosage can cause death. In the 1960s and 1970s, barbiturates were used to treat anxiety and insomnia but are no longer used for these purposes due to their serious adverse effects. Barbiturates are controlled substances under the Pharmacy Operations and Drug Scheduling Act. However, the misuse of barbiturates continues to occur with street use as a “downer” to counteract the effects of cocaine and methamphetamine.

Mechanism of Action

Barbiturates produce sedation and drowsiness by altering cerebellar function and depressing the actions of the brain and sensory cortex.

Indications for Use

They are primarily used as an anticonvulsant. It is also used as a sedative and may also be used as a pre-anesthetic agent.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Do not use it for children less than 1 month of age. Barbiturates may harm the fetus during pregnancy. Avoid use in geriatric patients.

Adverse/Side Effects

Patients may experience CNS depression, suicidal thoughts or behaviors, GI disturbances, rashes, or some blood disorders that can be fatal. The concomitant use of alcohol or other CNS depressants may produce additive CNS depressant effects that can cause death. Barbiturates can be habit-forming.

Contraindicated for use in patients with severe renal and hepatic disorders, severe respiratory depression, dyspnea or airway obstruction, and porphyria.

Patient Teaching & Education

The patient should be advised to take the prescribed medication as directed. Patients who undergo prolonged therapy should not discontinue treatment abruptly, as this may cause the onset of seizure activity. These medications may cause drowsiness and should not be taken with alcohol or other CNS depressants. Female patients using oral contraceptives should also use non-hormonal-based contraceptives during therapy involving barbiturate use.

Overdosage

The onset of symptoms following a toxic oral exposure to phenobarbital may not occur until several hours following ingestion. If an overdose occurs, consult with a Poison Information Center (1-800-567-8911).

Phenobarbital Medication Card

Now, let’s take a closer look at the medication grid for phenobarbital in the table below. Medication cards like this are intended to assist students in learning key points about each medication. Because medication information constantly changes, nurses should always consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medication. Basic information related to each class of medication is outlined below. Prototype or generic medication examples are also hyperlinked to a free resource at Daily Med. On the home page, enter the drug name in the search bar to read more about the medication.

Medication Card: Phenobarbital

Generic Name: phenobarbital

Prototype/Brand Name: Phenobarb

Mechanism: Alters cerebellar function and depresses actions of the brain and sensory cortex.

Therapeutic Effects

- Reduction in seizures

- Sedation

Administration

- Orally, IM, or IV

- Taper dose; do not stop abruptly

Indications

- When sedation is needed

- Seizures

Contraindications

- Severe renal and hepatic disorders.

- Severe respiratory depression, dyspnea, or airway obstruction; porphyria.

- Not for children under 1 month.

- Not for use in pregnancy.

- Avoid in geriatric patients.

Side Effects

- CNS depression; overdosage can cause death

- It may cause suicidal thoughts or behavior

- Respiratory depression

- GI: Nausea and vomiting

Nursing Considerations

- Take as directed.

- May be habit-forming

- Do not take with other CNS depressants or alcohol

Benzodiazepines

Lorazepam, a benzodiazepine with antianxiety, sedative, and anticonvulsant effects, is available for oral, intramuscular, or intravenous routes of administration. Benzodiazepines are controlled substances because they have a potential for abuse and may lead to dependence.

Mechanism of Action

Benzodiazepines bind to specific GABA receptors to potentiate the effects of GABA.

Indications for Use

Benzodiazepines are used for sedation, anti-anxiety, and anticonvulsant effects. Lorazepam injection is indicated for the treatment of status epilepticus. It may also be used in adult patients for pre-anesthetic medication to produce sedation (sleepiness or drowsiness), relieve anxiety, and decrease the ability to recall events related to the day of surgery. Oral lorazepam is used to treat anxiety disorders.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Benzodiazepines may cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women. Children and the elderly are more likely to experience paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines, such as tremors, agitation, or visual hallucinations. Elderly or debilitated patients may be more susceptible to the sedative and respiratory depressive effects of lorazepam. Therefore, these patients should be monitored frequently and have their dosage adjusted carefully according to the patient’s response; the initial dosage should not exceed 2 mg. Dosage for patients with severe hepatic insufficiency should be adjusted carefully according to patient response.

Adverse/Side Effects

A Black Box Warning states that concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death.

The most important risk associated with the intravenous use of lorazepam injection is respiratory depression. Accordingly, airway patency must be ensured, and respiration must be monitored closely. Ventilatory support should be given as required. The additive central nervous system effects of other drugs, such as phenothiazines, narcotic analgesics, barbiturates, antidepressants, scopolamine, and monoamine-oxidase inhibitors, should be considered when these other drugs are used concomitantly with or during the period of recovery from, lorazepam injection. Sedation, drowsiness, respiratory depression (dose-dependent), hypotension, and instability may occur with oral dosages as well. The use of benzodiazepines may lead to physical and psychological dependence. Withdrawal symptoms may accompany the abrupt termination of treatment. Benzodiazepines should be prescribed for short periods only (e.g., 2 to 4 weeks). The treatment period should not be extended without reevaluation of the need for continued therapy.

Overdosage

Overdosage of benzodiazepines is usually manifested by varying degrees of central nervous system depression, ranging from drowsiness to coma. Treatment of overdosage is mainly supportive until the drug is eliminated from the body. Vital signs and fluid balance should be carefully monitored with close patient observation. An adequate airway should be maintained, and assisted respiration should be used as needed. The benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil may be used for hospitalized patients in the management of benzodiazepine overdose. There is a risk of seizure in association with flumazenil treatment, particularly in long-term benzodiazepine users. If an overdose occurs, consult with a Poison Information Center (1-800-567-8911).

Patient Teaching & Education

Patients who receive lorazepam should be cautioned that driving a motor vehicle, operating machinery, or engaging in hazardous or other activities requiring attention and coordination should be delayed for 24 to 48 hours following administration or until the effects of the drug, such as drowsiness, have subsided. Patients should be advised that if they get out of bed unassisted within 8 hours of receiving lorazepam, they risk falling and potentially sustaining injury. Alcoholic beverages should not be consumed for at least 24 to 48 hours after receiving lorazepam injectable due to the additive effects on central nervous system depression seen with benzodiazepines in general. Elderly patients should be instructed that lorazepam injection may make them very sleepy for a period longer than 6 to 8 hours following surgery.

Lorazepam Medication Card

Now, let’s take a closer look at the medication card for lorazepam. Because medication information constantly changes, nurses should consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medication.

Medication Card: Lorazepam

Generic Name: lorazepam

Prototype/Brand Name: Ativan

Mechanism: Binds to specific GABA receptors to potentiate the effects of GABA.

Therapeutic Effects

- Reduced anxiety

- Reduced seizure activity

Administration

- SL, PO, IV

- Use cautiously in the elderly and (may have paradoxical impacts)

- Consider a smaller dose for liver dysfunction

Indications

- To relieve anxiety, reduce seizure activity, or as a pre-anesthetic

Contraindications

- Severe hepatic impairment; respiratory depression; acute narrow-angle glaucoma.

- Pregnancy and lactation.

- Not for children under 12

Side Effects

- Oversedation and drowsiness

- Potentially Fatal: Respiratory depression

- Overdosage can cause coma and death

- SAFETY: Unsteadiness and fall risk. Concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death. Flumazenil is used for overdose.

Nursing Considerations

- Monitor for fall risk

- Take as prescribed

- Do not stop taking drugs (in long-term therapy) without consulting a health care provider.

- Avoid operating motor vehicles or heavy machinery

- Do not consume alcohol

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Activity 9.5

A patient who has been experiencing panic attacks is prescribed lorazepam. Upon further discussion with the patient, the nurse discovers that the patient is planning to go on a cruise with her husband next week and plans to use a scopolamine patch to control nausea. The patient states, “I can’t wait to relax on the cruise ship and have a margarita as we leave port!”

What important patient education should the nurse provide to the patient about the new prescription for lorazepam?

CNS Stimulants

CNS stimulants are clinically used for the treatment of attention-deficit disorders to help calm hyperkinetic individuals and to help them focus on one activity for a more extended period. The majority of CNS stimulants are controlled substances.

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate is an example of a CNS stimulant that is often used to treat ADHD.

Mechanism of Action

Methylphenidate stimulates the brain and acts similarly to amphetamines. It is thought to block the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine into the presynaptic neuron.

Indications for Use

Methylphenidate is used for ADHD.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Methylphenidate is typically prescribed to patients over the age of 6. It should be avoided in patients with known structural cardiac abnormalities, cardiomyopathy, serious heart rhythm arrhythmias, or coronary artery disease. Blood pressure and heart rate should be monitored in all patients.

CNS stimulants have been associated with weight loss and a slowing of growth rate in pediatric patients. They also increase the risk of peripheral vasculopathy, such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, with signs and symptoms of fingers or toes feeling numb, cool, painful, and/or changing color from pale to blue to red.

Methylphenidate is contraindicated in patients using a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) or who have used one within the preceding 14 days. If paradoxical worsening of symptoms or other adverse reactions occur, the dosage should be reduced or, if necessary, discontinued.

Administer methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release capsules orally once daily in the morning. Extended-release capsules should not be crushed, chewed, or divided. Monitor for signs of misuse and dependence while in therapy.

Adverse/Side Effects

Serious cardiovascular events have occurred, with sudden death reported in association with CNS-stimulant treatment in pediatric patients with structural cardiac abnormalities or other serious heart problems. Sudden death, stroke, and myocardial infarction have also been reported in adults with CNS-stimulant treatment at recommended doses. Methylphenidate may cause increased blood pressure and increased heart rate. The use of stimulants may cause psychotic or manic symptoms in patients with no prior history and may cause priapism (painful or prolonged penile erections). The most common adverse reactions (greater than 5% incidence) were headache, insomnia, upper abdominal pain, decreased appetite, and anorexia. Alcohol should be avoided because it may cause a rapid release of the drug in extended-release formulations.

Overdose

If an overdose occurs, consult with a Poison Information Center (1-800-567-8911).

Patient Teaching & Education

There are several important topics to address with patients and/or parents of minor children.

Misuse and Dependence: Advise patients that methylphenidate is a controlled substance that can be misused and lead to dependence. Instruct patients that they should not give methylphenidate to anyone else. Advise patients to store methylphenidate in a safe, preferably locked, place to prevent misuse. Advise patients to comply with laws and regulations on drug disposal. Advise patients to dispose of remaining, unused, or expired methylphenidate through a medicine take-back program if available.

Serious Cardiovascular Risks: Advise patients that there is a serious potential cardiovascular risk, including sudden death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension. Instruct patients to contact a healthcare provider immediately if they develop symptoms such as exertional chest pain or unexplained syncope.

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Increases: Instruct patients that methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release capsules can elevate their blood pressure and pulse rate.

Psychiatric Risks: Advise patients that methylphenidate can cause psychotic or manic symptoms, even in patients without a prior history of psychotic symptoms or mania.

Priapism: Advise patients of the possibility of painful or prolonged penile erections and seek immediate medical attention if this occurs.

Circulation Problems in Fingers and Toes: Instruct patients beginning treatment with methylphenidate about the risk of peripheral vasculopathy and associated signs and symptoms: fingers or toes may feel numb, cool, painful, and/or may change color from pale to blue to red. Instruct patients to report to their physician any new numbness, pain, skin color change, or sensitivity to temperature in fingers or toes or any signs of unexplained wounds appearing on fingers or toes.

Suppression of Growth: Advise parents that methylphenidate may cause slowing of growth and weight loss.

Alcohol Effect: Advise patients to avoid alcohol while taking extended-release capsules.

Methylphenidate Medication Card

Now, let’s take a closer look at the medication card for methylphenidate. Because medication information constantly changes, nurses should always consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medication.

Medication Card: Methylphenidate

Generic Name: methylphenidate

Prototype/Brand Name: Ritalin, Concerta

Mechanism: Thought to block the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine into the presynaptic neuron.

Therapeutic Effects

- Increased mental focus and attention

Administration

- Administer in the morning.

- Do not crush or chew

- Safe for use over the age of 6

- Avoid with CVS disease

Indications

- Attention deficit disorders

Contraindications

- Use of an MAOI within 14 days

- Cardiac disease

- Pregnancy and lactation

Side Effects

- Serious side effects: Cardiac and perfusion. Priapism. Mania/ psychosis

- Common side effects: headache, insomnia, upper abdominal pain, decreased appetite, and anorexia. Gynecomastia

- May slow growth in pediatric patients

- SAFETY: High misuse potential. Monitor BP and HR. Monitor growth/wt in children.

Nursing Considerations

- Controlled substance

- Parent teaching

- Patients should avoid alcohol

- Monitor for misuse

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Activity 8.6

A 12-year-old male child has been diagnosed with ADHD after his parents and teachers became concerned with his inability to concentrate and his poor impulse control in the classroom. The physician has prescribed methylphenidate.

What topics should the nurse reinforce while educating the child and his parents about this medication?

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are used to treat depression and other mental health disorders, as well as other medical conditions such as migraine headaches, chronic pain, and premenstrual syndrome. Antidepressants increase levels of neurotransmitters in the CNS, including serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, and norepinephrine. Treatment is based on the belief that alterations in the levels of these neurotransmitters are responsible for causing depression.

This module will discuss four classes of antidepressants: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). These medications are compared in Table 8.7.

TCAs and MAOIs are referred to as first-generation antidepressants because they were first marketed in the 1950s. SSRIs, SNRIs, and other miscellaneous medications such as bupropion are called second-generation antidepressants and are popular because of fewer side effects like sedation, hypotension, anticholinergic effects, or cardiotoxicity.

Safety warnings (Black Box) are in place for all classes of antidepressants used with children, adolescents, and young adults for a higher risk of suicide. All patients receiving antidepressants should be monitored for signs of worsening depression or changing behavior, especially when the medication is started or dosages are changed.

For more information on different types of anti-depressants, watch this video.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were one of the original first-generation antidepressants. Due to the popularity of SSRIs and SNRIs, TCAs are now more commonly used to treat neuropathic pain and insomnia.

Mechanism of Action

TCAs tend to have sedative and anticholinergic effects. They act by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake of NE and 5-HT into nerves. The choice of TCA depends on individual response and tolerance to the drug.

Indications for Use

TCAs are used to treat depression, chronic neuropathic pain, and insomnia.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

TCAs are often administered at bedtime due to sedating effects and are contraindicated with MAOIs.

Geriatric patients are particularly sensitive to the anticholinergic side effects of tricyclic antidepressants. Peripheral anticholinergic effects include tachycardia, urinary retention, constipation, dry mouth, blurred vision, and exacerbation of narrow-angle glaucoma. Central nervous system anticholinergic effects include cognitive impairment, psychomotor slowing, confusion, sedation, and delirium. Elderly patients taking amitriptyline may be at increased risk for falls. Elderly patients should be started on low doses of amitriptyline and observed closely.

After prolonged administration, abrupt cessation of treatment may produce nausea, headache, and malaise. The dose should be gradually tapered, but transient symptoms may still occur.

TCAs should not be used in children and those who are pregnant or lactating.

Adverse/Side Effects

Adverse effects of TCAs are a result of their blockade effects on various receptors, often resulting in anticholinergic adverse effects such as constipation, urinary retention, and drowsiness. Blockage of adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors can cause cardiac conduction disturbances and hypotension. Histaminergic blockage can cause sedation, and serotonergic blockade can alter the seizure threshold and cause sexual dysfunction.

Black Box Warnings are in place for all classes of antidepressants used with children, adolescents, and young adults for higher risk of suicide. Patients receiving antidepressants should be monitored for signs of worsening depression or changing behavior, especially when the medication is started or dosages are changed.

TCAs are contraindicated as follows:

- Myocardial infarction.

- Concurrent use of MAOIs.

- Pregnancy, lactation.

- Preexisting cardiovascular disorders.

- Angle-closure glaucoma, urinary retention, prostate hypertrophy, GI or GU surgery.

- History of seizures.

- Hepatorenal diseases.

There are also several drug interactions, such as cimetidine, fluoxetine, and ranitidine, increased therapeutic and adverse effects of TCAs. Using oral anticoagulants can increase serum levels of anticoagulants and increase the risk of bleeding. TCAs should not be used concurrently with MAOIs, which increases the risk of a severe hyperpyretic crisis.

Overdosage

Death may occur from overdosage with this class of drugs. Multiple drug ingestion (including alcohol) is common in deliberate tricyclic antidepressant overdose. If an overdose occurs, consult with a Poison Information Center (1-800-567-8911).

Patient Teaching & Education: Due to the increased risk of suicidality with antidepressants, patients and their family members or caregivers should be instructed to immediately report any sudden changes in mood, behaviors, thoughts, or feelings. The potential side effects discussed above should be reviewed.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI)

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are second-generation antidepressants and have fewer side effects than TCAs and MAOIs. Fluoxetine and citalopram are commonly used SSRIs.

Mechanism of Action

SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin.

Indications for Use

SSRIs are primarily used to treat depression but are also used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder, bulimia, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, other forms of anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, and migraines.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

The onset of fluoxetine’s antidepressant effect develops slowly for up to 12 weeks.

Use caution in patients who are taking other CNS medications or who have liver dysfunction. This drug is contraindicated with MAOIs—monitor for increased suicide ideation in all populations, as well as for the development of serotonin syndrome. Patients should avoid grapefruit juice due to its effect on the CYP3A4 enzyme, which affects the bioavailability of the medication.

Adverse/Side Effects

Black Box Warnings are in place for all classes of antidepressants used with children, adolescents, and young adults for higher risk of suicide. Patients receiving antidepressants should be monitored for signs of worsening depression or changing behavior, especially when the medication is started or dosages are changed.

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)-like reactions has been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs, particularly with concomitant use of serotonergic drugs, drugs that impair the metabolism of serotonin (including MAOIs), or with antipsychotics or other dopamine antagonists. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome may include mental status changes (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, hyperthermia), neuromuscular aberrations (e.g., hyperreflexia, incoordination), and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Serotonin syndrome, in its most severe form, can resemble neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), which includes hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability with possible rapid fluctuation of vital signs, and mental status changes. Patients should be monitored for the emergence of serotonin syndrome or NMS-like signs and symptoms.

Other side effects include rash, mania, seizures, decreased appetite and weight, and increased bleeding associated with the concomitant use of fluoxetine and NSAIDs, aspirin, warfarin, or other drugs that affect coagulation, hyponatremia, anxiety, and insomnia.

Abrupt discontinuation may cause several adverse effects, so a gradual reduction in the dose rather than abrupt cessation is recommended whenever possible.

Patient Teaching & Education

Patients should be careful to take medications as directed. Abrupt discontinuation may cause anxiety, insomnia, and increased nervousness. Additionally, orthostatic blood pressure changes are common during medication therapy. Patients may also be increasingly drowsy or exhibit some confusion. Use of SSRI medications with alcohol or other CNS depressant drugs should be avoided.

Patients, family, and caregivers should monitor patients carefully for suicidality. Other side effects include possible decreased libido, urinary retention, constipation, and increased photosensitivity.

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Activity

A 32-year-old female visits the nurse practitioner with concerns about “feeling tired all the time,” “having difficulty concentrating,” “problems sleeping,” and “just generally feeling down.” The nurse practitioner prescribed fluoxetine.

The patient tells the nurse, “One of my friends told me I have to be careful, or I might get serotonin syndrome if I take medication.”

- What places a patient at risk for serotonin syndrome, and what symptoms should the nurse teach the patient about this condition?

- The nurse knows that anyone starting an antidepressant is at risk for suicidal thoughts. How should the nurse therapeutically discuss this potential adverse effect with the patient?

- What potential common side effects should the nurse discuss with the patient?

The patient states, “I can’t wait to feel better again. How soon will this medication work?”

- What is the nurse’s best response?

Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI)

Venlafaxine is an example of a Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI).

Mechanism of Action

Venlafaxine inhibits serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, with weak inhibition of dopamine reuptake.

Indications for Use

SNRIs are indicated for the treatment of a major depressive disorder.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

SNRIs are contraindicated with MAOIs or within 14 days of use of an MAOI. Dosage adjustment is required for use in patients with renal and/or liver disease. Elderly patients are at greater risk for developing hyponatremia. Use with caution with other serotonin medications.

Adverse/Side Effects

Black Box Warnings are in place for all classes of antidepressants used with children, adolescents, and young adults for higher risk of suicide. Patients receiving antidepressants should be monitored for signs of worsening depression or changing behavior, especially when the medication is started or dosages are changed.

SNRI medication may cause a sustained increase in blood pressure. Other side effects include serotonin syndrome, insomnia, anxiety, decreased appetite, weight loss, mania, hyponatremia, increased bleeding (especially with the concomitant use of fluoxetine and NSAIDs, aspirin, warfarin, or other drugs that affect coagulation), elevated serum cholesterol, somnolence, and nausea.

Patient Teaching & Education

Patients should take medications as directed, and the dose should be tapered prior to discontinuation. They may also become increasingly drowsy or dizzy. SNRI medications should not be used with alcohol or other CNS depressant drugs. Patients, their families, and their caregivers should monitor them carefully for suicidality.

Monoamine Oxidase inhibitors (MAOI)

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are first-generation antidepressants. A significant disadvantage to MAOIs is their potential to cause a hypertensive crisis when taken with stimulant medications or foods containing tyramine.

Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of MAOIs is not fully understood. Still, it is presumed to be linked to the potentiation of monoamine neurotransmitter activity in the central nervous system resulting from its inhibition of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). MAO inactivates norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, and serotonin. By inhibiting MAO, the levels of these transmitters rise, thus creating anti-depressive effects.

Indications for Use

MAOIs are indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adult patients who have not responded adequately to other antidepressants.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Serious interactions with several medications, as well as foods and beverages containing tyramine, have been reported; check drug labeling before administering. Safety has not been established with the pediatric population. The elderly population is at increased risk for postural hypotension and serious adverse effects. Misuse and dependence have been reported. Withdrawal effects can continue for several weeks after discontinuation.

Adverse/Side Effects

Black Box Warnings are in place for all classes of antidepressants used with children, adolescents, and young adults for higher risk of suicide. Patients receiving antidepressants should be monitored for signs of worsening depression or changing behavior, especially when the medication is started or dosages are changed.

Use with caution due to the risks of hypertensive crisis, serotonin syndrome, and increased suicidality. A hypertensive crisis is defined by severe hypertension (blood pressure greater than 180/120 mm Hg) with evidence of organ dysfunction. Symptoms may include occipital headache (which may radiate frontally), palpitations, neck stiffness or soreness, nausea or vomiting, sweating, dilated pupils, photophobia, shortness of breath, or confusion. Either tachycardia or bradycardia may be present and may be associated with constricting chest pain. Seizures may also occur. Intracranial bleeding, sometimes fatal, has been reported in association with the increase in blood pressure. See more information about serotonin syndrome in the “SSRI” section.

Other potential side effects include mania, orthostatic hypotension, hepatotoxicity, seizures, hypoglycemia in diabetic patients, decreased appetite and weight loss, dizziness, headache, drowsiness, and restlessness. Patients should be advised that it may impair their machinery or driveability. MAOIs should be discontinued if hepatotoxicity occurs.

Patient Teaching & Education

Patients should be careful to take medications as directed. It may take up to 4 weeks to see the effects of the drug. They should avoid abrupt cessation of therapy to prevent withdrawal symptoms. Patients should avoid alcohol, other CNS depressants, and tyramine-containing products for two weeks after treatment is discontinued. Patients should be advised regarding the signs of hypertensive crisis and to immediately report headache, chest or throat tightness, and palpitations to the provider.

Now, let’s take a closer look at a medication grid that compares these classifications of anti-depressants.

Medication cards like this are intended to help students learn key points about each medication. Because medication information is constantly changing, nurses should always consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medications. Basic information related to each class of medication is outlined below.

Comparing Types of Anti-depressants

| Class | Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA) | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) | Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) |

| Generic Prototype (Brand) | amitriptyline (Elavil)

nortriptyline (Aventyl) |

fluoxetine (Prozac)

citalopram (Celexa) sertraline (Zoloft) |

venlafaxine (Effexor) | Tranylcypromine (Parnate) |

| Mechanism | Inhibits presynaptic reuptake of NE and 5-HT | Inhibits reuptake of serotonin | Inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, with weak inhibition of dopamine reuptake. | Inhibits the enzyme monoamine oxidase, therefore allowing for increased levels of norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, and serotonin. |

| Indications and Therapeutic Effects | Treats depression and insomnia.

Chronic neuropathic pain. |

Primarily used to treat depression. Also used for OCD and other forms of anxiety and stress disorders. | Treats major depressive disorder. | Treats major depressive disorder in adults who have not responded to other antidepressants. |

| Contraindications | MI and CV disease, pregnancy, lactation, glaucoma, urine retention, BPH, GI/GU surgery. History of seizures. Hepatorenal diseases.

Drug interactions: Cimetidine, Fluoxetine, ranitidine, anticoagulants, MAOIs |

MAOIs. Use caution with liver dysfunction.

Drug interactions: Caution with the use of NSAIDs and other drugs that affect coagulation. |

MAOIs.

Caution with use of NSAIDs and other drugs that affect coagulation. Caution in elderly. |

SSRIs, SRNIs, and many other drugs.

Caution in the elderly, pregnancy, lactation, and children. Food interactions: food containing tyramine. |

| Side Effects | Anticholinergic effects, CV effects, Sedation, sexual dysfunction, altered seizure threshold. | Rash, mania, seizures, decreased appetite and weight, increased bleeding, anxiety, insomnia, and photosensitivity. | CV effects: sustained high blood pressure, high cholesterol, rash, mania, decreased appetite and weight, increased bleeding, anxiety, insomnia, somnolence, nausea, and constipation. | Mania, decreased appetite and weight, drowsy/restlessness, hepatotoxicity, seizures, and hypoglycemia in diabetic patients. |

| Administration and Nursing Considerations | Safety: Increased risk of suicidality.

Taper to discontinue. Monitor orthostatic blood pressure. The effect may take 4 weeks. Caution for hepato/renal toxicity. Give at bedtime. Immediately report signs and symptoms of suicidality. |

Safety: Increased risk of suicidality and serotonin syndrome.

Taper to discontinue. Monitor Orthostatic blood pressure. The effect may take 12 weeks. It may cause drowsiness. No alcohol or CNS depressants. Immediately reports signs and symptoms of suicidality or serotonin syndrome. Avoid grapefruit. |

Safety: Increased risk of suicidality and serotonin syndrome.

Taper to discontinue. The effect may take 8 weeks. It may cause drowsiness. No alcohol or CNS depressants. Immediately reports signs and symptoms of suicidality or serotonin syndrome. Avoid grapefruit. Caution for hepato/renal toxicity. |

Safety: Increased risk of suicidality, serotonin syndrome, and hypertensive crises.

Taper to discontinue. The effect may take 4 weeks. It may cause drowsiness. No alcohol or CNS depressants. Immediately report signs and symptoms of suicidality, serotonin syndrome, and/or hypertensive crises. Caution with liver dysfunction. Avoid tyramine. |

Antimania

Mood stabilizers are used to treat bipolar affective disorder. Lithium was the first medication used to treat this disorder and is sometimes referred to as an anti-mania drug because it can help control the mania that occurs in bipolar disorder. Lithium must be closely monitored with a narrow therapeutic range.

Lithium

Mechanism of Action

Lithium alters sodium transport in nerve and muscle cells and causes a shift toward intraneuronal metabolism of catecholamines, but the specific biochemical mechanism of lithium action in mania is unknown.

Indications for Use

Lithium is indicated in the treatment of manic episodes of bipolar disorder and as a maintenance treatment for individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Lithium must be closely monitored with a narrow therapeutic serum range of 0.6 to 1.2 mmol/L. Serum sodium levels should also be monitored for potential hyponatremia.

The drug is contraindicated in renal or cardiovascular disease, severe dehydration, or sodium depletion and to patients receiving diuretics because the risk of lithium toxicity is very high in such patients.

Lithium can cause fetal harm in pregnant women. Safety has not been established for children under 12 and is not recommended.

When given to a patient experiencing a manic episode, lithium may produce a normalization of symptomatology within 1 to 3 weeks.

Adverse/Side Effects

Black Box Warning: Lithium toxicity is closely related to serum lithium levels and can occur at doses close to therapeutic levels at 1.5 mEq/L. Facilities for prompt and accurate serum lithium determinations should be available before initiating therapy. Lithium can cause abnormal electrocardiographic (ECG) findings and risk of sudden death. Patients should be advised to seek immediate emergency assistance if they experience fainting, lightheadedness, abnormal heartbeats, or shortness of breath.

Signs of early lithium toxicity include diarrhea, vomiting, drowsiness, muscular weakness, and lack of coordination. Giddiness, ataxia, blurred vision, tinnitus, and a large output of dilute urine may be seen at higher levels. No specific antidote for lithium poisoning is known; treatment focuses on the elimination of the medication.

Fine hand tremors, polyuria, and mild thirst may persist throughout treatment.

Patient Teaching & Education

Patients should take medication as directed. It is important to note that antimanic drugs may increase dizziness and drowsiness. Additionally, if individuals have low sodium levels, it may predispose the patient to toxicity. Patients should also be advised that weight gain may occur.

Lithium Medication Card

Now, let’s take a closer look at the medication grid for lithium. Medication cards like this are intended to assist students in learning key points about each medication. Because medication information constantly changes, nurses should consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medication.

Medication Card: Lithium

Generic Name: lithium

Prototype/Brand Name: Lithane, Carbotlith

Mechanism: alters sodium transport in nerve and muscle cells to shift toward intraneuronal metabolism of catecholamines. Specific biochemical mechanism in mania is unknown.

Therapeutic Effects

- Reduce symptoms of a manic episode

- Reduced frequency and intensity of manic episodes

Administration

- Monitor for signs of lithium toxicity

- Monitor serum lithium and sodium levels

Indications

- Treatment of manic episodes of bipolar disorder

- Maintenance for individuals with bipolar disorder.

Contraindications

- Renal and CVS disease

- Dehydration and use of diuretics.

- Children under 12

- Pregnancy and lactation

Side Effects

- Lithium toxicity (can cause sudden death)

- Hyponatremia

- Tremor

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Polyuria

- Thirst

- Dizzy and drowsy

- Weight gain

- SAFETY: S&S of lithium toxicity requires emergency assistance.

Nursing Considerations

- Take as directed

- When given during a manic episode, symptoms may resolve in 1-3 weeks

- Must be closely monitored with a narrow therapeutic serum range of 0.6 to 1.2 mmol/L.

- Serum sodium levels should also be monitored for hyponatremia.

Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Activity

A 42-year-old male was recently diagnosed with bipolar disorder after his partner became concerned about his extreme highs and lows in moods. His high mood swings were often associated with grandiose ideas, gambling, risky sexual behavior, and shopping sprees that were causing the couple to go bankrupt. The physician prescribed lithium.

- The patient states, “The doctor told me I am having manic episodes. What does that mean?” What is the nurse’s best response?

- The nurse knows that there is a risk of lithium toxicity. What are the symptoms of lithium toxicity, and how will it be prevented?

- The patient’s partner asks, “How quickly will the lithium work?” What is the nurse’s best response?

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat drug-induced psychosis, schizophrenia, extreme mania, depression that is resistant to other therapies, and other CNS conditions. Antipsychotics are sometimes referred to as tranquilizers because they produce a state of tranquility. First-generation antipsychotics, also called conventional antipsychotics, have similar mechanisms of action. An example of a conventional antipsychotic is haloperidol. Conventional antipsychotics have several potential adverse effects, and the selection of a medication is based on the patient’s ability to tolerate the adverse effects. Second-generation antipsychotics, also referred to as atypical antipsychotics, have fewer adverse effects. An example of an atypical antipsychotic is risperidone. Both conventional and atypical antipsychotics have a Black Box Warning, indicating that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.

1st and 2nd Generation Antipsychotics

Mechanism of Action

All antipsychotics block dopamine receptors in the brain. However, the precise mechanism of action has not been established. Conventional antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, block dopamine receptors in certain areas of the CNS, such as the limbic system and the basal ganglia. These areas are associated with emotions, cognitive function, and motor function, and blockage thus produces a tranquilizing effect in psychotic patients. However, several adverse effects are also caused by this dopamine blockade.

Second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics block specific dopamine 2 receptors and specific serotonin 2 receptors, thus causing fewer adverse effects.

Indications for Use

Haloperidol is primarily indicated for schizophrenia and Tourette’s disorder. Risperidone is primarily indicated for schizophrenia but is also used for acute manic episodes and for irritability caused by autism. Some atypical antipsychotics are also used as adjunct therapy for depression or nausea.

Nursing Considerations Across the Lifespan

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of cardiovascular events or infections such as pneumonia.

Haloperidol is contraindicated in patients with Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Patients who are concurrently taking lithium and antipsychotics should be monitored closely for neurotoxicity (weakness, lethargy, fever, tremulousness, confusion, and extrapyramidal symptoms), and symptoms should be immediately reported.

Adverse/Side Effects

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death due to cardiovascular or infection-related causes.

Conventional antipsychotic medications have several potentially serious adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and extrapyramidal symptoms. These adverse effects are due to the blockage of alpha-adrenergic, dopamine, endocrine, histamine, and muscarinic receptors.

| Potential Adverse Effects of Antipsychotic Medication | |

| Adverse Effect | Definition |

| Tardive Dyskinesia | Involuntary contraction of the oral and facial muscles (such as tongue thrusting) and wavelike movements of the extremities. |

| Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) | Potentially life-threatening adverse effects, including high fever, unstable blood pressure, and myoglobinemia. |

| Extrapyramidal Symptoms | Involuntary motor symptoms are similar to those associated with Parkinson’s disease. Includes symptoms such as akathisia (distressing motor restlessness) and acute dystonia (painful muscle spasms.) Often treated with anticholinergic medications such as benztropine and trihexyphenidyl. |

Second-generation or atypical antipsychotics are less likely to cause adverse effects but have the potential to do so. Atypical antipsychotics may also cause metabolic changes such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and weight gain.

Patient Teaching & Education

Advise the patient to take medication as directed. Medication doses should be evenly spaced throughout the day. This drug may take several weeks to manifest the desired effects. Patients should be advised regarding the possibility of extrapyramidal symptoms and that abrupt withdrawal may cause dizziness, nausea, vomiting, or uncontrolled movements of the mouth, tongue, or jaw. Additionally, the patient should be careful to avoid alcohol or other CNS depressants while using the medication.

Medication Card Comparing Antipsychotics

Now, let’s look closer at the medication grid for haloperidol and risperidone. Medication cards like this are intended to assist students in learning key points about each medication. Because information about medication is constantly changing, nurses should always consult evidence-based resources to review current recommendations before administering specific medication. Basic information related to each class of medication is outlined below.

| Comparing Types of Antipsychotics | ||||||

| Class | Generic Prototype (Brand) | Mechanism | Indication & Therapeutic Effect | Contraindications | Side Effects | Administration and Nursing Considerations |

| 1st Generation (Conventional)

|

haloperidol

(Halidol) |

Block dopamine receptors in certain areas of the CNS, such as the limbic system and the basal ganglia. | schizophrenia and Tourette’s disorder | Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies.

High risk for neurotoxicity with concurrent other antipsychotics |

CVS and Respiratory effects

Severe: Tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and extrapyramidal symptoms |

SAFETY: Falls related to sedation, motor instability, and postural hypotension |

| 2nd Generation (Atypical)

|

risperidone

(Risperidol) |

Block specific dopamine 2 receptors and specific serotonin 2 receptors, | acute manic episodes and for irritability caused by autism | High risk for neurotoxicity with concurrent other antipsychotics | Fewer adverse effects than conventional antipsychotics.

Metabolic changes such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and wt gain. |

Same as 1st Generation. |

Anticonvulsants

Medications used for seizures are called anticonvulsants or antiseizure drugs. Antiseizure drugs stabilize cell membranes and suppress the abnormal electric impulses in the cerebral cortex. These drugs prevent seizures but do not provide a cure. Antiseizure drugs are classified as CNS depressants. There are many types of medications used to treat seizures, such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, valproate, and levetiracetam.

There are three main pharmacological effects of antiseizure medications. First, they increase the activity threshold in the motor cortex, thus making it more difficult for a nerve to become excited. Second, they limit the spread of a seizure discharge from its origin by suppressing the transmission of impulses from one nerve to the next. Third, they decrease the speed of the nerve impulse conduction within a given neuron.