5 Defense and Immunity: Infection and Antimicrobials (Part 2)

This chapter is a continuation of the previous chapter.

Learning Objectives

- Identify populations who have an increased risk of infection.

- Describe common pathogens and methods of infection control.

- Distinguish between antimicrobial agents in terms of mechanism of action, indication for use, adverse effects, and implications for the nursing process.

- Apply knowledge of ways to minimize the emergence of drug-resistant microorganisms.

Viral Infections

A virus is a pathogen with a nucleic acid molecule within a protein coat. It requires a living host for replication. An invading virus may immediately cause disease or may remain relatively dormant for years. Diseases develop as a result of interference with the normal cellular functioning of the host, with the destruction of the virus by the immune system also requiring the death of the host cell.

Review of Prior Knowledge: Viruses

The learner needs to draw from previously learned knowledge to better understand pathophysiologic and pharmacologic conditions. The following videos are USEFUL RESOURCES for your review:

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the body’s immune system, specifically the CD4 cells (T cells), which are crucial for immune function. If left untreated, HIV can lead to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), the most severe phase of HIV infection, where the immune system is severely compromised, making the body vulnerable to opportunistic infections and certain cancers. Antiretroviral therapy is used for pharmacologic management of HIV.

HIV Infection

Pathophysiology

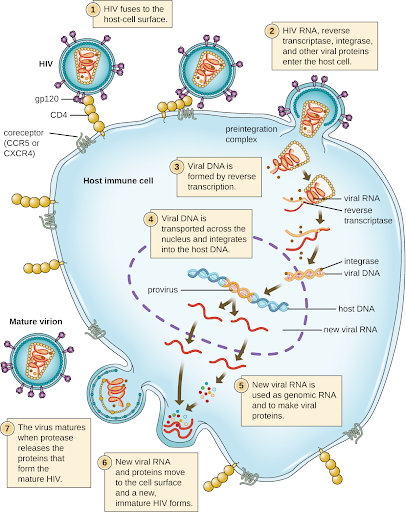

1. Entry and Infection: HIV targets and enters CD4 cells by binding to the CD4 receptor and co-receptors (CCR5 or CXCR4) on the cell surface. Once inside the cell, the viral RNA is reverse-transcribed into DNA by the enzyme reverse transcriptase.

2. Integration: The enzyme integrase then integrates the newly synthesized viral DNA into the host cell’s genome. This allows the virus to hijack the host cell’s machinery to produce new viral particles.

3. Replication: The infected CD4 cell produces viral proteins and RNA assembled into new virions. These new virions are then released from the host cell, ready to infect other CD4 cells.

4. Immune System Impact: Over time, HIV reduces the number of CD4 cells, weakening the immune system. This depletion leads to increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections and certain cancers, which define the progression to AIDS if left untreated.

Stages of HIV Infection

1. Acute HIV Infection: This is the initial stage of infection, occurring 2 to 4 weeks after exposure. Symptoms of the flu may resemble fever, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, rash, muscle and joint aches, and headache. High levels of virus are present in the blood, making the individual highly infectious.

2. Chronic HIV Infection: Also known as the asymptomatic or clinical latency stage, this period can last for several years. The virus is still active but reproduces at very low levels. Individuals may not have symptoms but can still transmit the virus.

3. AIDS: Without treatment, chronic HIV infection typically progresses to AIDS in about ten years. The immune system is severely damaged at this stage, and the body becomes susceptible to opportunistic infections and cancers. Common symptoms include rapid weight loss, recurring fever, chronic diarrhea, sores, pneumonia, and memory loss.

References:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). (2021). HIV/AIDS Overview. Retrieved from NIAID

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from WHO

- Hepatitis A, B, C, or E: Hepatitis viruses are a group of viruses that cause liver inflammation. There are five main types: Hepatitis A(HAV), Hepatitis B (HBV), Hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis D(HDV), and Hepatitis E( HEV). A different virus causes each type and has unique modes of transmission, severity, and outcomes. Learning Resource: Overview of Viral Hepatitis

3. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common respiratory virus that typically causes mild, cold-like symptoms. However, it can be severe, especially in infants and older adults. RSV is a leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children under one year old. The virus spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Most children are infected with RSV by age two, and reinfections can occur throughout life. There is no specific treatment for RSV, but supportive care, such as hydration and oxygen therapy, can help manage symptoms. Preventive measures include good hygiene practices and, for high-risk infants, a monthly injection of palivizumab during RSV season.

4. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the novel coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in late 2019. It primarily spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. The virus can cause a range of illnesses, from mild respiratory infections to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and death. Common symptoms include fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but can also include loss of taste or smell, fatigue, and gastrointestinal issues. Preventive measures include wearing masks, practicing social distancing, frequent hand washing, and vaccination. Vaccines have been developed and distributed globally to combat the spread and impact of COVID-19.

General Symptoms of Viral Infection

Viral infections often present with various general symptoms varying in severity and duration. Common symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, muscle and joint aches, and malaise. Respiratory symptoms such as cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, and runny nose are typical, especially in infections like the flu or the common cold. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, may occur in viral gastroenteritis. Additionally, viral infections can cause skin rashes and lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes). Symptoms can vary based on the specific virus, the affected body system, and the individual’s immune response.

Comparison of General Symptoms: Bacterial vs Viral Infections

| Symptoms | Bacterial Infections | Viral Infections | Similarities |

| Onset and Duration | Sudden onset, longer duration without antibiotics | Gradual onset, typically self-limiting | Both can present with a range of onset speeds |

| Fever | High-grade, often with chills and sweats | Low to moderate-grade, high in some viruses | Both can cause fever |

| Pain | Localized pain (throat, ear, sinus, abdomen) | Generalized muscle and joint aches, sore throat

|

Both can cause pain

|

| Swelling and Redness | Localized inflammation, possible abscess formation | Less common, but can occur (e.g., swollen glands)

|

Both can cause inflammation.

|

| Respiratory Symptoms | Productive cough with colored sputum | Dry or non-productive cough, runny nose, sneezing |

Both can cause cough and respiratory issues |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Abdominal pain, prolonged diarrhea | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, usually short-lived

|

Both can cause gastrointestinal symptoms. |

| Skin and Rash | Less common, except for localized infections | Common in some infections (e.g., measles, chickenpox) | Both can cause skin rashes in some cases |

| Response to Antibiotics | Improves with antibiotics | No improvement with antibiotics | |

| Specific Tests and Cultures | Elevated WBC with neutrophils, positive cultures | Elevated WBC with lymphocytes, specific viral tests | Both may require lab tests for diagnosis |

| Severity and Complications | More likely to lead to severe complications if untreated | Generally milder, but can be severe in some cases | Both can lead to complications |

Key Points- Understanding viral infections involves several key concepts:

1. Virus Structure:

•Genome: Viruses have either DNA or RNA genomes, which carry genetic information.

•Capsid: A protein shell that encases the viral genome, protecting it and aiding in host cell infection.

•Envelope: Some viruses have an outer lipid membrane derived from the host cell, which can help evade the immune system.

2. Transmission:

•Direct Contact: Spread through physical contact, such as touching or kissing.

•Droplet Transmission: Spread through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks.

•Airborne Transmission: Spread through aerosols that remain suspended in the air.

•Vector-Borne Transmission: Spread by vectors like mosquitoes or ticks.

•Fecal-Oral Transmission: Spread through ingestion of contaminated food or water.

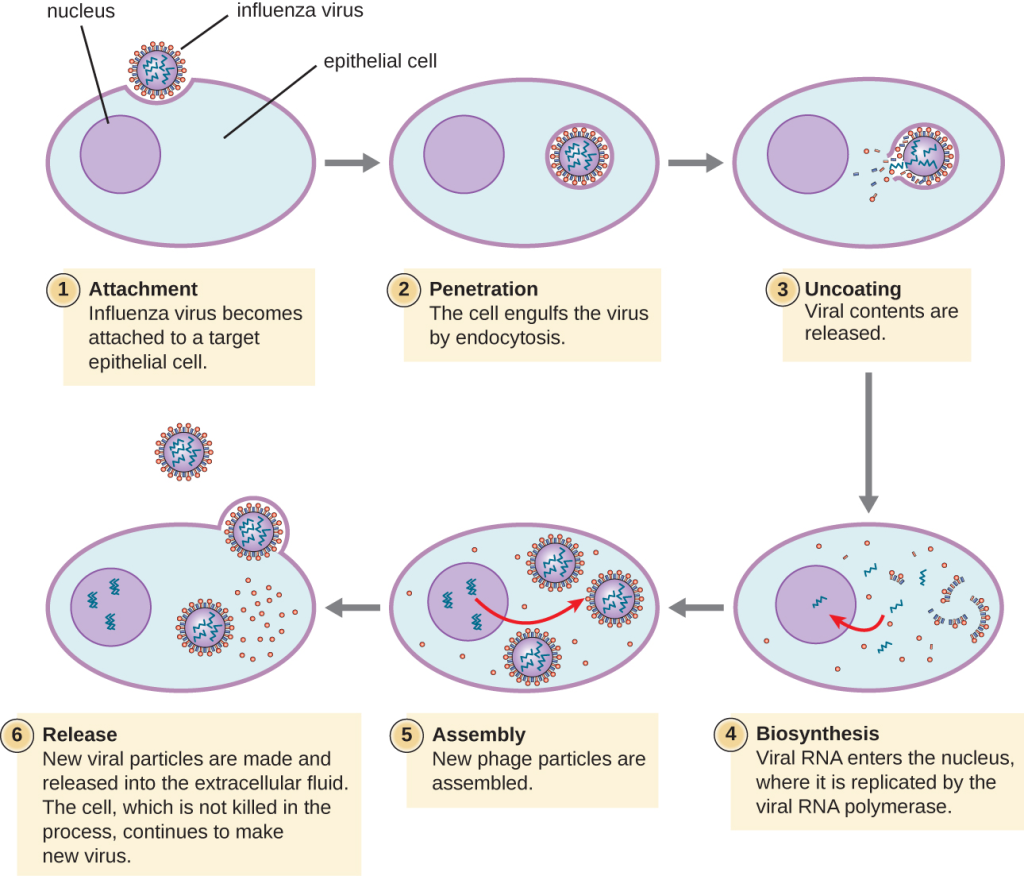

3. Host Cell Interaction:

•Attachment: Viruses attach to specific receptors on the host cell surface.

•Entry: Viruses enter the host cell via endocytosis or membrane fusion.

•Replication: Viruses hijack the host cell machinery to replicate their genomes and produce viral proteins.

•Assembly: New viral particles are assembled from replicated genomes and proteins.

•Release: New viral particles are released from the host cell, often destroying it.

4. Immune Response:

•Innate Immunity is the body’s initial defense, including physical barriers (skin, mucous membranes) and immune cells (macrophages, dendritic cells) that recognize and respond to pathogens.

•Adaptive Immunity is the body’s specialized defense involving T cells and B cells that recognize specific viral antigens and create a targeted response, including the production of antibodies.

5. Symptoms and Disease Progression:

•Incubation Period: The time between virus exposure and symptom onset.

•Acute Infection: Rapid onset of symptoms, with the immune system usually clearing the virus.

•Chronic Infection: The virus persists in the body for long periods, potentially causing ongoing or recurrent symptoms.

•Latent Infection: The virus remains dormant within the host cell, potentially reactivating later.

6. Prevention and Treatment:

•Vaccination: Provides immunity by exposing the immune system to viral antigens without causing disease.

•Antiviral Medications: Drugs that inhibit viral replication and reduce the severity and duration of illness.

•Hygiene Practices: Hand washing, using hand sanitizers, and wearing masks to reduce transmission.

•Quarantine and Isolation: Separating infected individuals to prevent the spread of the virus.

7. Epidemiology:

•Outbreak: A sudden increase in disease cases in a specific area.

•Epidemic: A widespread occurrence of an infectious disease in a community at a particular time.

•Pandemic: An epidemic that has spread across multiple countries or continents, usually affecting many people.

Source: Centers for Disease Control.

Learning Resource: Overview of Viruses

III. Fungal Infections

A fungus is any spore-producing microorganism, which includes yeasts, molds, and mushrooms. Fungi typically grow and proliferate in moist areas of the body, such as between the toes, in the groin, under the panniculus, and under the breasts. In an otherwise healthy individual, fungi do not cause disease and are contained by the body’s natural flora. In the immunocompromised individual, they can result in infections that lead to death. Obese people and people with diabetes are also more susceptible to fungal infections.

Common fungal infections:

- Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot): this infection can occur in healthy individuals as well

- Candidiasis (yeast infection)

- Aspergillosis (lung infection caused by mold)

- Histoplasmosis (fungal lung infection)

Learning Resource: Overview of Fungal Infections

IV. Parasitic Infections

Parasites or protozoa generally infect individuals with compromised immune responses. They are typically found in dead material in water and soil and are spread by the fecal-oral route by ingesting food or water contaminated with parasitic spores or cysts. The disease may develop in an otherwise healthy individual when the spores invade organs and stimulate an immune response, interfering with the normal functioning of the organ system.

Common parasitic infections:

- Giardiasis

- Cryptosporidium

- Toxoplasmosis

- Malaria

Learning Resource: Approach to Parasitic Infections

III. Clinical Reasoning and Decision-making: Pharmacologic Management of Infections

The previous sections were reviews of antimicrobial basics. The next sections will take a closer look at specific classes of drugs used to treat infections ( anti-infectives) and administration considerations, therapeutic effects, adverse effects, and specific patient teaching. This unit examines the importance of the nursing process in guiding the nurse who administers anti-infective medications. The nursing process consists of assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation of interventions, and evaluation. These basic steps lead to sound clinical reasoning and safe decision-making in administering drugs related to infection.

Assessment: Although there are numerous details to consider when administering medications, it is always important to think more broadly about what you are giving and why. As a nurse administering an antimicrobial, you must remember some important broad considerations.

First, let’s think of the WHY. Recognizing cues…

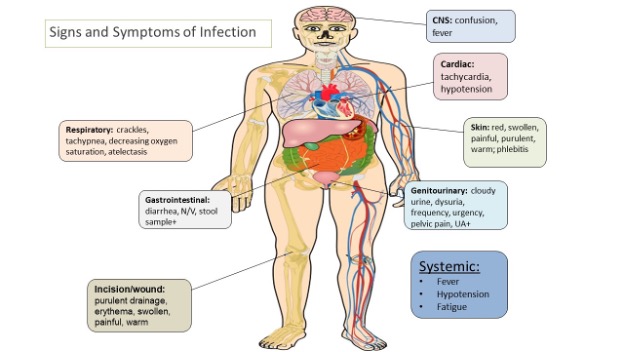

Antimicrobials are given to prevent or treat infection. If a patient is prescribed an antimicrobial, an important piece of the nursing assessment is to recognize and analyze cues. The nurse should look for signs and symptoms of infection and always know WHY the patient receives an antimicrobial to evaluate whether the patient is improving or deteriorating effectively. Remember, the nurse must assess how this medication is working, and having pre-administration assessment information is an important part of this process.

To define a baseline, typical data that a nurse collects at the start of a shift include:

- temperature

- heart rate

- blood pressure

- respiratory rate, and

- white blood cell count.

- Focused assessments are then made based on the type of infection. For example, if it is a wound infection, the wound should be assessed for redness, inflammation, drainage type and amount, and pain. If it is a respiratory infection, the nurse should assess the patient’s lung sounds and type/consistency of respiratory expectorate. If a patient has a urinary tract infection (UTI), the urine and symptoms related to a UTI (pain with urination, cloudy urine, foul-smelling urine) should be assessed.

- The following image summarizes some common signs and symptoms of infection (by system) that a nurse needs to monitor for.

Additionally, whenever a patient has an infection, it is important to continually monitor for the development of sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by severe infection. As you recall from the previous chapter, early signs of sepsis include new-onset confusion, elevated heart rate, decreased blood pressure, increased respiratory rate, and elevated fever.

Additional baseline information to collect before administering any new medication order includes patient history, current medication use, including herbals or other supplements, and history of allergy or a previous adverse response. Many patients with an allergy to one type of antimicrobial agent may experience cross-reactivity to other classes. This information should be appropriately communicated to the prescribing provider before administering any antimicrobial medication.

When nurses have completed a thorough assessment, they can prioritize their concerns/hypotheses before implementing further intervention.

Interventions

When administering the antimicrobial medication, the nurse needs to anticipate any additional interventions associated with the medications. For example, antimicrobials often cause gastrointestinal upset (GI), such as nausea, diarrhea, etc. The nurse may need to refine their assessments and interventions accordingly. The patient should be educated about these potential side effects, and proper interventions should be taken to minimize these occurrences. For example, the nurse may instruct the patient to take certain antimicrobials with food to

diminish the chance of GI upset, whereas other medications should be taken on an empty stomach for optimal absorption.

Hypersensitivity/allergic reactions are always a potential adverse reaction, especially when administering the first dose of a new antibiotic, and the nurse should monitor closely for these symptoms and respond appropriately by immediately notifying the prescriber. Hypersensitivity reactions are immune responses that are exaggerated or inappropriate to an antigen and can range from itching to anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency that can cause life-threatening respiratory failure. Early signs of anaphylaxis include, but are not limited to, hives and itching, the feeling of a swollen tongue or throat, shortness of breath, dizziness, and low blood pressure.

Evaluation

Finally, it is important to evaluate the patient’s response to a medication. With antimicrobial medications, the nurse should assess for the absence of or decreasing signs of infection, indicating the patient is improving. It is important to document these findings to reflect the patient’s trended response.

It is also important for the nurse to promptly identify and communicate signs of worsening infection to the provider. For example, increasing white blood cell count, temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate may indicate that the patient’s body is experiencing a life-threatening response to the infection. These signs of worsening clinical assessment require prompt intervention to prevent further clinical deterioration. Additionally, patients receiving antibiotics should be closely monitored for developing a complication called “C. diff,” resulting in frequent, foul-smelling stools. C. diff stands for Clostridium difficile, a spore-forming, gram-positive bacterium that colonizes the human intestinal tract after the normal gut flora has been disrupted (frequently associated with antibiotic therapy). C. diff is one of the most common healthcare-associated infections and a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among older adult hospitalized patients. Management of C-diff requires the implementation of modified contact precautions, including using soap and water, not hand sanitizer (as this does not kill the spores), and antibiotic therapy.

Administration Considerations

Antimicrobial drug therapy involves special considerations to ensure the therapeutic drug effect is achieved while maintaining patient safety and minimizing complications.

Let’s consider some of the variables that may impact antimicrobial administration:

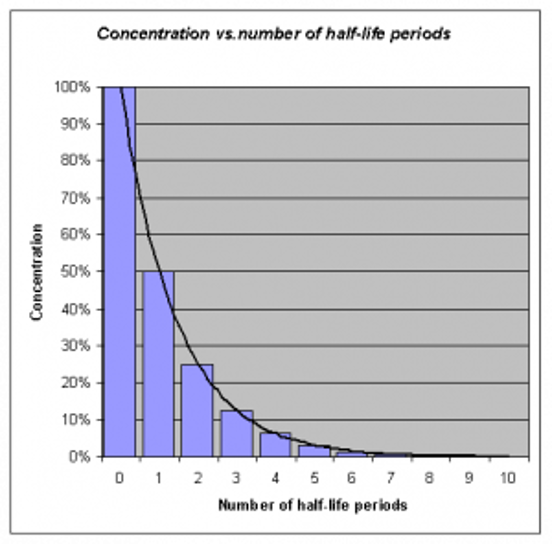

Half-Life

Many antimicrobial medications are administered to ensure that a certain therapeutic level of medication remains in the bloodstream and may require interval or repeated dosing throughout the day. For example, the half-life, or rate at which 50% of a drug is eliminated from the plasma, can vary significantly between drugs. Some drugs have a short half-life of only 1 hour and must be given multiple times a day, but other drugs have half-lives exceeding 12 hours and can be given as a single dose every 24 hours. Although a longer half-life can be considered an advantage for an antibacterial when it comes to convenient dosing intervals, the longer half-life can also be a concern for a drug with serious side effects. Medications with a longer half-life and more concerning side effects will exert these side effects over a longer period.

See the figure below for an illustration of half-lives and the time it takes for a medication to be eliminated from the bloodstream.

Lifespan Considerations

Most medications are calculated specifically based on the patient’s size, weight, and renal function. Patient age and size are especially vital in pediatric patients. A child’s stage of development and the size of their internal organs greatly impact how the body absorbs, digests, metabolizes, and eliminates medications.

Liver & Renal Function

Additionally, many antimicrobial medications require tailored dosing based on individual patient responses and the potential impact of the medication on the patient’s liver and renal function. For more information about the effects of liver and renal function on medications, refer to Chapter 1 regarding metabolism and excretion.

Often, pharmacists and providers collect peak and trough drug blood levels to determine how an individual patient’s body responds to an antimicrobial. Follow-up interval dosing is then prescribed based on these blood levels. This is especially important for older adults or those with known liver/renal impairment. Individuals with diminished liver and renal function are more prone to drug toxicity because of the reduced ability of the body to metabolize or clear medications from the body. For more information about peak and trough levels, refer to Chapter 1 regarding medication safety.

Dose Dependency/Time Dependency

The goal of antimicrobial therapy is to select an optimal dosage that will result in a clinical cure while reducing complications or significant side effects. Many medications may be dose-dependent. This means there is a more significant killing of bacteria with increasing levels of antibiotics. For example, fluoroquinolones are dose-dependent medications with the treatment goal of optimizing the amount of the drug. Other medications are time-dependent. Time-dependent medications have optimal bacterial-killing effects at lower doses over a longer period of time. Time-dependent antimicrobials exert the greatest effect by binding to the microorganism for an extensive length of time. Penicillin is an example of a time-dependent medication that aims to optimize the duration of exposure.

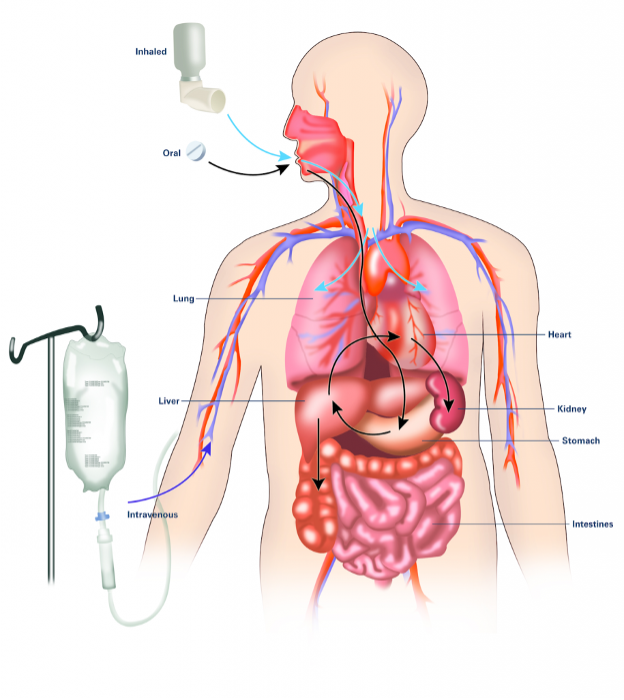

Route

It is also important to consider the route of drug administration within the patient’s body. Many of us may have been prescribed oral antibiotics and have filled our prescriptions and completed the drug regimen within the comfort of our own homes. However, many types of infections or disease processes do not respond well to the use of oral antimicrobial therapy. For these diseases, patients may require intravenous or intramuscular injections. Patients requiring intravenous or intramuscular injections may need to be hospitalized, have home health nursing arranged, or travel to the hospital/clinic for their therapy. Concerns with treatment compliance exist with all routes of administration. For more information about considerations regarding routes of administration, refer to Chapter 1 on absorption. The figure below is an illustration of three common routes of antimicrobial medications within the body:

Drug Interactions

Two antibacterial drugs may be administered together for the optimum treatment of select infections. Concurrent drug administration produces a synergistic interaction that is better than the efficacy of either drug alone. In this case, two is truly better than one! A classic example of synergistic drug combinations is trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Individually, these two drugs provide only bacteriostatic inhibition of bacterial growth, but combined, the drugs are bactericidal.

Although synergistic drug interactions benefit the patient, antagonistic interactions produce harmful effects. Antagonism can occur between two antimicrobials or between antimicrobials and non-antimicrobials being used to treat other conditions. The effects vary depending on the drugs involved. Still, antagonistic interactions cause diminished drug activity, decreased therapeutic levels due to elevated metabolism and elimination, or increased potential for toxicity due to decreased metabolism and elimination.

Let’s consider an example of these antagonistic interactions.

Many antibacterial are absorbed most effectively from the stomach’s acidic environment. However, if a patient takes antacids, the antacids increase the stomach’s pH and negatively impact the absorption of the antibacterial, thus decreasing their effectiveness in treating an infection.

IV. Pharmacologic Management of Infections: Antibacterial

Antibacterial management is a critical aspect of healthcare and nursing practice, focusing on the effective use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections while mitigating the risk of antibiotic resistance. This involves a responsible selection of appropriate antibiotics, accurate dosing, careful treatment efficacy, and patient response monitoring. Key elements to consider in this practice include stewardship programs that promote the responsible use of antibiotics, education of healthcare providers and patients about the dangers of overuse and misuse, and adherence to infection prevention protocols to reduce the spread of resistant bacteria. Additionally, it is essential for healthcare professionals to stay informed about the latest research and guidelines on antimicrobial resistance and to implement evidence-based practices in clinical settings. Effective antibacterial management enhances patient outcomes and supports public health by preserving the efficacy of existing antibiotics.

Nurses play pivotal roles in the effective and safe management of antibacterial treatments, which are integral to controlling infections and preventing the escalation of antibiotic resistance. Their responsibilities include:

- Patient Education: Nurses educate patients on the proper use of antibiotics, including adherence to prescribed dosages and schedules, the importance of completing the full course even if symptoms improve, and the risks associated with misuse.

- Monitoring and Compliance: They closely monitor patients for signs of improvement or side effects, ensuring compliance with treatment protocols. This vigilance helps adjust treatments as needed in consultation with physicians, optimize therapeutic outcomes, and minimize adverse effects.

- Infection Control: Nurses implement rigorous infection control measures in healthcare settings to prevent the spread of infections and reduce the need for antibiotics, thus helping to decrease the development of resistance.

- Stewardship Advocacy: Nurses advocate for the judicious use of antibiotics within antimicrobial stewardship programs. They collaborate with the healthcare team to select the most appropriate antibiotic therapy based on current guidelines and individual patient needs.

- Data Collection and Reporting: Nurses contribute to the surveillance of antibiotic efficacy and resistance by collecting and reporting data on antibiotic use and resistance patterns. This information is crucial for ongoing evaluation and improvement of treatment protocols.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Nurses collaborate with a multidisciplinary team, including pharmacists, physicians, and infection control specialists, to ensure a coordinated approach to antibacterial management. This maximizes the effectiveness of interventions to manage infections and prevent antibiotic resistance.

By fulfilling these roles, nurses ensure that antibacterial management is both effective and safe, thereby safeguarding patient health and contributing to global efforts to combat antibiotic resistance. Nurses can competently perform these roles with pharmacologic knowledge of antibiotics.

Active Learning Strategy: In Chapter 1-Start Here, a Drug Template that learners can use to organize information was presented : Drug Card Template.

- Complete Drug Cards for the following classes of antibiotics with the information found in the hyperlinked resources:

- Filling-up the cards with your handwritten notes can be very helpful. You also have an option to use your tablets, or PCs, highlighting the important information around concepts of infection, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and nursing practice/clinical considerations.

- You will share these drug cards with your fellow learners in Blackboard(Learning Management System), and use these in group/collaborative activities.

- The nurse will administer a wide variety of antibacterial, and you can use this resource as your guide: Bacteria and Antibacterial Medications

- The antibacterial medications below are exemplars of antibacterial that the nurse will likely administer in community and acute care settings.

Clinical Learning Exercise: MS-Discharge Planning

Discharge Planning: Includes home health care for a follow-up on antibiotic therapy, a referral to a pulmonary rehabilitation program, and arranging for a follow-up visit with her primary care physician; Education: Patient and family education on signs of potential complications or relapse, the importance of pneumonia vaccine considering her age and medical history, and strategies to improve overall lung health. The nurse also provides education on antibiotic resistance.

V. Pharmacologic Management of Infections: Antibacterial

Antiviral management is a crucial component of healthcare and nursing practice, focusing on effectively using antiviral medications to treat viral infections, prevent the spread of viruses, and mitigate the impact of viral diseases. This management requires a comprehensive approach that includes accurate diagnosis, timely initiation of therapy, and ongoing monitoring of treatment efficacy and patient adherence. Key elements to consider include understanding the mechanisms of action of antiviral drugs, the potential for resistance development, and the appropriate use of these medications in specific populations such as the immunocompromised. Nurses play a vital role in antiviral management by educating patients on the importance of adhering to prescribed treatment regimens, monitoring for adverse reactions and effectiveness of the therapy, and implementing infection control measures to prevent transmission. Additionally, nurses must stay informed about the latest developments in antiviral treatments and evolving viral threats to provide the most up-to-date care for their patients and advise on preventive measures, including vaccination, where available. Effective antiviral management improves patient outcomes and contributes to the broader public health goal of controlling viral diseases. Nurses are integral to the successful pharmacologic management of antiviral therapies, playing several critical roles that enhance patient outcomes and ensure the safe and effective use of antiviral medications.

Learning Activities:

- Complete Drug Cards and Pathophysiology Cards for the hyperlinked conditions and pharmacologic management below:

- Share your drug cards with your fellow learners–( refer to course discussions and assignments)

- Use these pathophysiology and drug cards to complete group project.

Unlike the complex structures of fungi or protozoa, viral structures are simple. Antiviral medications have several subclasses: anti-influenza, anti-hepatitis, and antiretroviral. Each subclass will be discussed in more detail below.

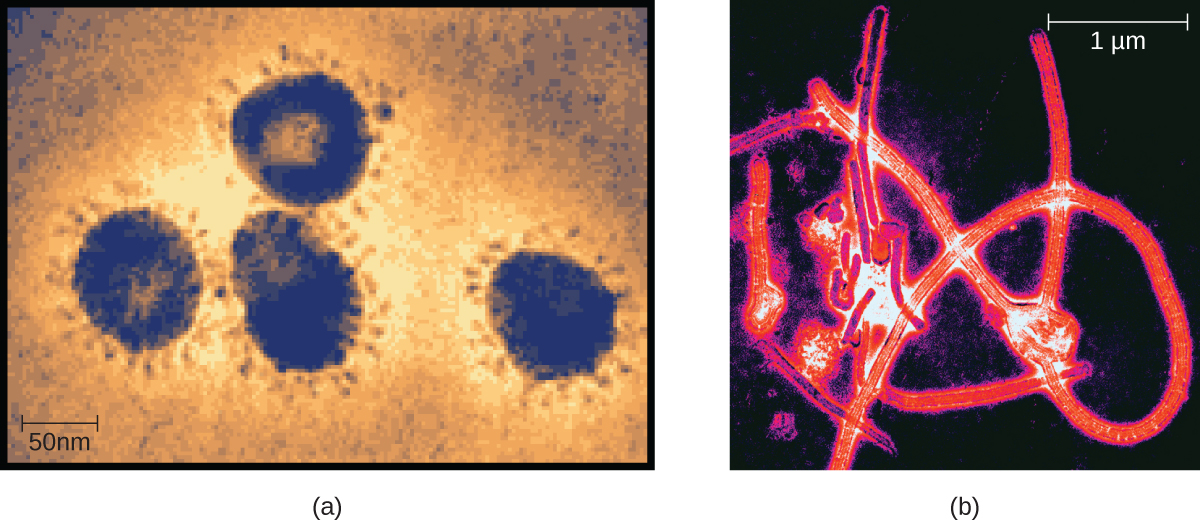

Images of viruses.

Images of Viruses (a) Members of the Coronavirus family can cause respiratory infections like the common cold, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Here, they are viewed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM).

(b) Ebolavirus, a member of the Filovirus family. (credit a: modification of work by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; credit b: modification of work by Thomas W. Geisbert).

Antinfluenza

- Mechanism of Action: Tamiflu prevents the release of virus from infected cells. The influenza virus is one of the few RNA viruses that replicate in the nucleus of cells. Antivirals block the release stage.

Influenza Virus Replication Stages

- Indications: Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) targets the influenza virus by blocking its release from the infected cells.

- Nursing Considerations: This medication does not cure influenza but can decrease flu symptoms and shorten the duration of illness if taken within 48 hours of symptom onset. Patients are prescribed the medication for prophylaxis against infection, known exposure, or to lessen the course of the illness. Patients who experience flu-like symptoms must start treatment within 48 hours of symptom onset.

- Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Common side effects include GI upset. Adverse effects include serious skin hypersensitivity reactions or neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially in children. Use cautiously in patients with renal failure, chronic cardiac or respiratory diseases, or any medical condition that may require imminent hospitalization.

- Health Teaching & Health Promotion: Patients treated with antiviral therapy should be instructed about the importance of medication compliance. They may also experience significant fatigue, so rest periods should be encouraged.

Antihepatitis

- Mechanism of Action: Antihepatitis medications inhibit the translation of viral mRNA into viral proteins. This action impedes the replication of the hepatitis virus.

- Indications: Antihepatitis medications like adefovir are used to treat chronic hepatitis, the hepatitis B virus, and the hepatitis C virus.

- Nursing Considerations: The medication improves liver function when active disease is present. Therapy is prolonged, typically over 1 year or indefinitely, based on the patient’s status.

- Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Adverse effects of antihepatitis medications include severe acute exacerbations of hepatitis B, nephrotoxicity, lactic acidosis, and severe hepatomegaly.

- Health Teaching & Health Promotion: Patients receiving treatment for antihepatitis medications should also be offered HIV testing to ensure that they do not have an unrecognized or untreated HIV infection. Antihepatitis medications may promote resistance to antiretroviral in patients with chronic Hepatitis B infection. Patients must understand that they should not stop taking medication unless directed by a healthcare provider. Monitor hepatic function several months after stopping therapy.

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

- Viruses with complex life cycles, such as HIV, can be more difficult to treat. These viruses require antiretroviral medications that block viral replication, often called antiretroviral therapy (ART). Additionally, antiretroviral fall under the class of antiviral medications.

- HIV attaches to an immune cell’s cell surface receptor and fuses with the cell membrane. Viral contents are released into the cell, where viral enzymes convert the single-stranded RNA genome into DNA and incorporate it into the host genome.

- Mechanism of Action: Antiretroviral impede virus replication.

- Indications: Antiretroviral such as lamivudine-zidovudine are used for the treatment of illnesses like HIV.

- Nursing Considerations: Many antiretroviral may impact renal function; therefore, the patient’s urine output and renal labs should be monitored carefully for signs of decreased function.

- Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Adverse side effects of antiretroviral medications include lactic acidosis and severe hepatomegaly. Patients should cease medication immediately if pancreatitis occurs.

- Health Teaching & Health Promotion: Patients treated with antiviral therapy should be instructed about the importance of antiretroviral compliance. They may also experience significant fatigue, so rest periods should be encouraged.

VI. Pharmacologic Management of Infections: Antifungals

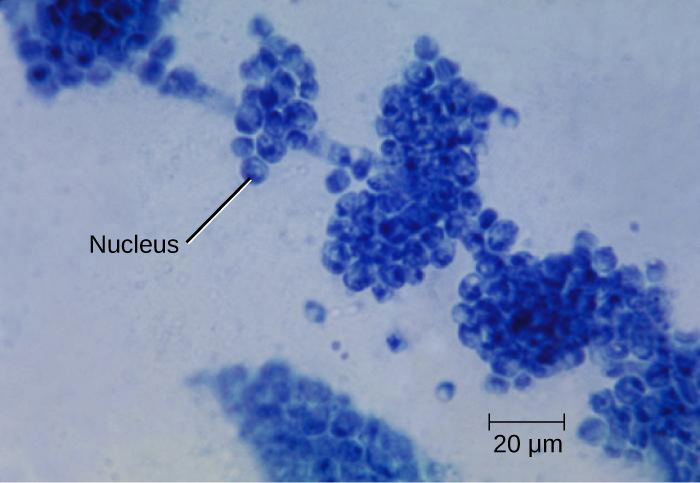

Fungi are important to humans in a variety of ways. Microscopic and macroscopic fungi have medical relevance, but some pathogenic species can cause mycoses (illnesses caused by fungi). See Figure below for a microscopic image of Candida albicans, the causative agent of yeast infections. Some pathogenic fungi are opportunistic, meaning they mainly cause infections when the host’s immune defenses are compromised and do not normally cause illness in healthy individuals. Fungi are also major sources of antibiotics, such as penicillin from the fungus Penicillium.

Antifungals

- Mechanism of Action: Antifungals disrupt ergosterol biosynthesis of the cell membrane, increasing cellular permeability and causing cell death.

- Indications: There are several classes of antifungals, each with their indications:

- Imidazoles include miconazole, ketoconazole, and clotrimazole, which are used to treat fungal skin infections such as tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), tinea cruris (jock itch), and tinea corporis (ringworm of the body).

- Triazole drugs, including fluconazole, can be administered orally or intravenously for the treatment of several types of systemic yeast infections, including oral thrush and cryptococcal meningitis, both of which are prevalent in patients with AIDS. Triazoles also exhibit more selective toxicity, compared with imidazoles, and are associated with fewer side effects.

- Allylamines, a structurally different class of synthetic antifungal drugs, are commonly used topically for the treatment of dermatophytic skin infections like athlete’s foot, ringworm, and jock itch. Oral treatment with terbinafine is also used for fingernail and toenail fungus, but it can be associated with the rare side effect of hepatotoxicity.

- Polyenes are a class of antifungal agents naturally produced by certain actinomycete soil bacteria and are structurally related to macrolides. Common examples include nystatin and amphotericin B. Nystatin is typically used as a topical treatment for yeast infections of the skin, mouth, and vagina, but may also be used for intestinal fungal infections. Amphotericin B is used for systemic fungal infections like aspergillosis, cryptococcal meningitis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and candidiasis. Amphotericin B was the only antifungal drug available for several decades, but its use has been associated with serious side effects, including nephrotoxicity.

- Nursing Considerations: Administration guidelines will vary depending on the type of fungal infection being treated. It is important to monitor the affected area’s response and examine class-specific administration considerations to monitor patient response.

- Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Common side effects of antifungal medications can include skin irritations and rashes. Additional adverse effects include hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, hypokalemia, and ototoxicity.

- Health Teaching & Health Promotion: The patient should be advised to follow dosage instructions carefully and finish the drug, even if they feel their symptoms have resolved. The patient should report any skin rash, abdominal pain, fever, or diarrhea to the provider. The patient should be monitored carefully for unexplained bruising or bleeding, which may be a sign of liver dysfunction.

- Patient Teaching & Education: The patient should be advised to follow dosage instructions carefully and finish the drug, even if they feel their symptoms have resolved. The patient should report any skin rash, abdominal pain, fever, or diarrhea to the provider. The patient should be monitored carefully for unexplained bruising or bleeding, which may be a sign of liver dysfunction.

Learning Acitivity

- Create drug cards enumerated below. Open the links to essential information.

- Share your drug cards with your fellow learners. These cards are essential information for a collaborative/group activity.

VII. Pharmacologic Management of Infections: Anthelmintics

Antimalarials

Malaria is a prevalent protozoal disease impacting individuals across the world.

- Indications for Use: Antimalarials are used to prevent or treat malaria.

- Mechanism of Action: Antimalarial agents target specific intracellular processes that impact cell development.

- Nursing Considerations across the Lifespan: Antimalarial agents are safe for all age groups. Dose adjustments are not needed for renal or liver dysfunction.

- Special Administration Considerations: Antimalarial medications may impact hearing and vision, so patients should be monitored carefully for adverse effects. Additionally, they may cause GI upset, so patients should be instructed to take them with food.

- Patient Teaching & Education: Patients should receive instruction to take medication as prescribed and adhere to the full prescription regimen. Patients should minimize additional mosquito exposure using preventative means such as repellents, protective clothing, netting, etc. Patients on chloroquine therapy should also avoid alcohol. Chloroquine can be extremely toxic to children and should be safely stored and out of reach. Patients receiving antimalarial therapy may have increased sensitivity to light and should be counseled to wear protective glasses to prevent ocular damage. Treatment often requires sustained regimens of six months or greater, so patients should be monitored carefully for adherence and compliance.

Antiprotozoals

Antiprotozoal drugs target infectious protozoans, such as Giardia, an intestinal parasite that infects humans and other mammals and causes severe diarrhea.

- Indications: Metronidazole is an example of an antiprotozoal antibacterial medication gel that is commonly used to treat acne rosacea, bacterial vaginosis, or trichomonas. Metronidazole IV treats Giardia and serious anaerobic bacterial infections such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff).

- Mechanism of Action: Many antiprotozoal agents work to inhibit protozoan folic acid synthesis, subsequently impairing the protozoal cell.

- Special Administration Considerations: It can be administered PO, parenterally, or topically. Orally is the preferred route for GI infections. The nurse should monitor the patient carefully for side effects such as seizures, peripheral neuropathies, and dizziness. Psychotic reactions have been reported with alcoholic patients taking disulfiram.

- Patient Teaching & Education: Patients taking antiprotozoal medications should receive education regarding the need for medication compliance and prevention of reinfection. They should be advised that the medication may cause dizziness and dry mouth. Additionally, the medication may cause darkening of the urine. They should also avoid alcoholic beverages during medication therapy to prevent a disulfiram-like reaction. If patients are being treated for protozoal infections such as trichomoniasis, they should be advised that sexual partners might be sources of reinfection, even if asymptomatic. Partners should also receive treatment. Patient teaching should include the avoidance of alcohol during therapy.

Key Takeaways

The links below will take you to an overview of the targeted infections. To complete your drug cards, open the links to the treatment/drugs used for these conditions:

VIII. Getting-it-together: Clinical Application

Clinical decision-making exercise – ANTIVIRAL THERAPY: Follow the unfolding case below , reflect on the following and create a concept map of all factors that will provide rationale for a nursing plan of care:

- Who is the patient? What is their story?

- What is the pathophysiology of the patient’s medical/surgical diagnosis?- create a pathophysiology card

- What are the manifestations(S/Sx) and associated functional problems of the patient?

- What medications are prescribed for the patient?— create your drug cards

- What are the actions of the medications? How will they help the patient’s conditions/problems?

- What are the expected outcomes of the medications? What will the medication do to the body/ physiologic changes? What are the implications to the nurse’s plan of action? (Clinical Judgment, Nursing Process, safety concerns)

- What will happen to the drug when given to the patient? What are the implications to the nurse’s plan of action? (Clinical Judgment, Nursing process, safety concerns)

Patient JD, male, 42 years old, HIV-positive for eight years, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, Current Medications: (Antiretroviral therapy: Efavirenz, Emtricitabine, Tenofovir (Atripla), Lisinopril (calcium-channel blocker) and Atorvastatin( antilipidemic)

JD presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine follow-up visit. He is feeling fatigued and having a persistent headache for the past week. He also mentions occasional dizziness and mild nausea.

Further assessment of JD shows:

Vital Signs: Blood Pressure: 142/90 mmHg; Heart Rate: 88 bpm; Respiratory Rate: 16 breaths/min; Temperature: 98.6°F (37°C); Weight: 180 lbs (82 kg)

Lab Results:•CD4 Count: 500 cells/mm³; •HIV Viral Load: Undetectable; Lipid Panel: Elevated LDL cholesterol

The nurse reviewed with JD the potential side effects of Efavirenz (an antiretroviral) and discussed options for managing these effects. The nurse recommended to the healthcare team ( provider) the need to evaluate the possibility of adjusting antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications.

Inter-professional Collaboration:

Clinical Decision Points by the Healthcare Team:

•Should John’s ART regimen be adjusted to reduce side effects?

•What interventions ( pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) can be implemented to manage his elevated cholesterol and blood pressure?

•Consider switching Efavirenz to an alternative with fewer CNS side effects.

•Discuss lifestyle modifications to manage cholesterol and hypertension.

•Collaborate with the healthcare team to evaluate the need for medication adjustments.

Reflect on the following questions, prepare your answers, and share them with your peers:

- What are the rationales behind clinical decisions made for JD?

- How do different medications interact and affect patient outcomes?

- What are the strategies for managing ART side effects and ensuring adherence?

- How do pathophysiology and pharmacology knowledge guide decision-making?

Clinical Decision-making Exercise _Antifungal therapy: (Histoplasmosis): A patient’s journey

Watch Correa’s Story Parts 1-5 , reflect and take notes of your answers. Be ready to share with your fellow learners:

- Who is the patient? What is their story?

- What is the pathophysiology of the patient’s medical/surgical diagnosis?

- What are the manifestations(S/Sx) and associated functional problems of the patient?

- What medications are prescribed for the patient?

- What are the actions of the medications? How will they help the patient’s conditions/problems?

- What are the expected outcomes of the medications? What will the medication do to the body/ physiologic changes? What are the implications to the nurse’s plan of action? (Clinical Judgment, Nursing Process, safety concerns)

- What will happen to the drug when given to the patient? What are the implications to the nurse’s plan of action? (Clinical Judgment, Nursing process, safety concerns)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Awrv62uP16Y

(cont..) Histoplasmosis: A Patient’s Story Parts 2-5

References:

Abbas, A. K., Lichtman, A. H., & Pillai, S. (2017). Cellular and Molecular Immunology (9th ed.). Elsevier.

Centers fo

Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Chain of Infection. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/index.html

Elmore, S. (2007). Apoptosis: A Review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicologic Pathology, 35(4), 495-516. DOI:

Delves, P. J., Martin, S. J., Burton, D. R., & Roitt, I. M. (2017). Roitt’s Essential Immunology (13th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Giddens, J. (2017). Concepts for Nursing Practice (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

Janeway, C. A., Travers, P., Walport, M., & Shlomchik, M. J. (2001). Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease (5th ed.). Garland Science.

Murray, P. R., Rosenthal, K. S., & Pfaller, M. A. (2016). Medical Microbiology (8th ed.). Elsevier

Murphy, K., & Weaver, C. (2016). Janeway’s Immunobiology (9th ed.). Garland Science.

Plotkin, S. A., Orenstein, W. A., & Offit, P. A. (2010). Vaccines (5th ed.). Saunders.

World Health Organization. (2022). Infection prevention and control. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/infection-prevention-control

Attributions:

This chapter is designed as a learning material for students in fundamentals of nursing level and is largely attributed to:

https://collection.bccampus.ca/textbooks/fundamentals-of-nursing-pharmacology-a-conceptual-approach-1st-canadian-edition-bccampus-400/#license

Several topic overviews are linked to to the Merck Manuals Professionals – Health & Medical InformationMerck Manualshttps://www.merckmanuals.com/

Media Attributions

- video_watch

- Signs and Symptoms of Infection is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Half Life is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Medications Routes