TWO–CAMPUS COLLEGE

(1965–70)

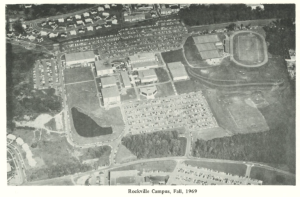

The fall of 1965 was without doubt one of the most difficult periods in the College’s nearly two decades of operation. A new president, the opening of a large, new campus on the outskirts of Rockville, new equipment which would not work, and a greatly expanded enrollment—these factors as well as others of lesser importance placed a heavy burden on everyone, administrative officers, members of the faculty, and students.

The new campus was raw and disappointing in appearance; no sod, no trees or shrubbery, plenty of dirt and dust, and “boxes” for buildings of unimaginative design—“late minimum security” as it was humorously referred to among the faculty. Many people had had a hand in the planning of the campus: the educational consultants from Palo Alto, California, the College administration and faculty, the Board of Education Planning and Construction staffs, the Board of Trustees, the Superintendent of Schools, and of course the architects. Funding for the early phase of construction, according to John W. McLeod, one of the architects, did not allow for

…the “extra-heavy” load that would be placed on the initial stage by virtue of the need to develop roads, parking, storm sewers, utility services, etc., not alone for the first few buildings, but “oversized” to accept later expansion without “redoing” everything each time an additional unit was projected. Thus the initial budget was “stretched” to the point where many of the amenities one expects on a college campus were eliminated or deferred.¹

Faculty offices were among “the amenities” omitted, despite the plans and previous requests. When the instructors arrived in September, they found, instead, large rooms designated “Faculty Work Areas,” in which a half dozen or more desks, chairs, and book cases were placed. A year later, following the strenuous objections of the faculty, the “bull pens” were partitioned into small faculty offices.

It would have been difficult enough for a new president to come to a single-campus community college which had been experiencing growing pains and mounting tensions between the administration and faculty, but to preside over a dual-campus institution involved with the opening of a large campus, was going to demand leadership of a high degree. Regrettably Dr. Hodson was unable to meet the challenge. He was fortunate to have, however, an administrative staff who, with the exception of the new Dean of Students, Dr. Bernard A. Hodinko,² provided continuity between the Deyo-Ehrbright administration and the new, although Dr. Hodson considered the transition in retrospect “a nearly impossible task.”³ Although he does not now favor a two-campus college as it “…violates one of the basic and primary principles of the community college movement, namely that the school be small enough and intimate enough that it can know and serve the needs of its students and its community,” Dr. Hodson, during the early months of his tenure at MJC, “obviously felt the advantages of the two campuses, though perhaps an administrative headache at times, outweighed any disadvantages the future evaluators might find.”⁴

During the early weeks of his administration, Dr. Hodson made two improvements which pleased the faculty as they were long overdue: salaries for summer session instructors were increased by 55 percent and more telephones in faculty offices (primarily for department chairmen) were provided, something which Dean Deyo had stubbornly refused to do.

With the opening of the second campus in September 1965, there were 33 curricula, including a new one in Police Science. The Art Curriculum had been revised so that students could either pursue a two-year program in advertising or a transfer program in art leading to a baccalaureate degree. Not only was Radiation Technology being offered, but Radiation Science as well. And there were now three secretarial curricula: Executive, Legal, and Medical Secretarial.

“Of all these,” according to Carol Lander, “the most imaginative of MJC’s programs was easily its course in Police Science, introduced… to alleviate the chronic shortage of police officers in the Washington-Metropolitan area.”⁵ Courses in this curriculum, which has recently been broadened and renamed Criminal Justice, included Police Administration, Defensive Tactics, Forensic Sciences, Criminal Law, Evidence, and Procedures, and Criminal Investigation. “As Montgomery County, Maryland continues to grow, so must its police force in number and quality,”⁶ wrote the author to Colonel James S. McAuliffe, Superintendent of Montgomery County Police in June 1962. Responding immediately to the suggestion of establishing a police science curriculum at MJC, McAuliffe stated: “I am reasonably sure that if such a course were made a part of the curriculum at the Junior College, the heads of the Police Departments in this area would be most keenly interested in employing those who satisfactorily complete the course.”⁷ Three years and one or two frustrations later, this program became a reality through the joint efforts of Dr. Erbstein, Mrs. Joan C. Lomax, and the author in cooperation with the Montgomery County Police Department and Mr. John Gagunin, Personnel Director of the County government. The curriculum has steadily grown in enrollment, having registered 64 students in 1969. (See Appendix D.)

During Dr. Hodson’s brief tenure at MJC, two new technical programs, Graphics and Registered Nursing,⁸ were established, Dr. Erbstein having again been instrumental in helping to bring the new curricula to the College. The former, which is now called Visual Communications Technologies (Advertising Arts and Printing Technology) was located on the Rockville Campus, and the latter, at the older campus in Takoma Park.

The opening of the new campus made possible a greatly expanded varsity athletic and physical education program, one of the recommendations made in a report submitted to the Dean and the Faculty of the College by the Athletic Board of Control in the spring of 1963.⁹ By 1969–70, there were no less than fifteen men and women varsity teams and 600 participants in intramural sports at the Rockville Campus.¹⁰ Though the Takoma Park Campus has lacked the extensive facilities enjoyed by the sister campus, it has provided, among other things in its athletic program, swimming courses at the Silver Spring YMCA pool and has recently fielded varsity basketball and soccer teams. (See Appendix E.) Moreover, during the past five years student interest in karate, the Japanese system of unarmed self-defense, has appeared on both campuses, resulting in the Karate Club gaining full membership in the American Bando Association in 1968–69.

† † †

Early in the fall of 1965 it was decided that the inauguration of the new president and the dedication of the new campus should be combined into one event. Accordingly, Saturday, December 11, 1965, was set aside for the occasion. Senator Joseph D. Tydings of Maryland was invited to deliver the convocation address; and Dr. William P. Fidler, then General Secretary of the American Association of University Professors and a parent of an alumnus of the College, was asked to speak at the luncheon following the convocation. “There is,” noted Fidler, “one important lesson which the older four-year institutions and the universities can learn from the better community colleges: the great importance of sound classroom teaching.” He concluded with “… the earnest hope that MJC will continue its striving toward excellence as an important unit in this region’s system of higher education.”¹¹

Meanwhile, hundreds of invitations were sent out to colleges, universities, learned societies, county and state leaders, and friends of the College. An attractive luncheon was arranged, to which, due to a limitation of funds, most of the faculty were not invited, thus exacerbating further the tensions between the faculty and Dr. Hodson and the Executive Dean, Dr. Eileen Kuhns.

“Isn’t it ironic?” asks one who was present at the occasion. “A splashy inauguration — for nothing — reflecting a hope that the new development and expansion of the College would soar…”¹² above past limitations. By the time of the presidential inauguration and campus dedication, despair and frustration characterized much of the thought and feeling among the faculty. The chief complaint of many was that the president was out of his depth and was therefore unable to give the kind of leadership the institution needed. Perhaps the president himself had come to feel by the time of his inauguration, or shortly thereafter, that it had been a mistake for him to accept the position at MJC. Six months later, immediately following commencement, Dr. Hodson set out for his new position as State Director of the Division of Education beyond High School in the Colorado State Department of Education.¹³ Looking back on his brief tenure at the College three years after his departure, he tartly observed: “I think that my major personal accomplishment at Montgomery Junior College was that I stayed for only one year.”¹⁴

† † †

About six weeks before commencement in 1966, Dr. Hodson announced the appointment of Dr. William C. Strasser, Jr., as the new Executive Dean of the Takoma Park Campus, a position which was comparable to that held by Dr. Eileen Kuhns at the Rockville Campus. A native of Washington, D.C., the new administrator of the older campus, who was then thirty-six years of age, had received his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. (Educational Administration and English) degrees from the University of Maryland. The year before his arrival at the College, Dr. Strasser had been appointed Assistant Director of Personnel for the Montgomery County Public Schools. And in 1964–65, he had served as a specialist in educational administration in the U.S. Office of Education, Washington, D.C. For two years before his coming to the Office of Education, the new Executive Dean of the Takoma Park Campus had been Assistant Dean and Assistant Professor in the School of Education, State University of New York at Buffalo.

As it turned out, Dr. Strasser did not have long to serve as Executive Dean of the campus at Takoma Park. With Dr. Hodson’s abrupt resignation in the spring, the Board of Trustees was faced with the necessity of appointing an acting president, it obviously being too late to find a replacement. Upon the recommendation of Dr. Homer O. Elseroad, who had meanwhile succeeded Dr. Whittier as the Superintendent of Montgomery County Schools, the Board appointed Dr. Strasser Acting President of the College with the understanding that he would be considered among other candidates for the permanent position.¹⁵

During the eight months in which he served as Acting President of MJC, Dr. Strasser quietly and efficiently carried out his responsibilities. Three of the four Board members elected four years previously on the so-called conservative slate were defeated in November 1966, the fourth, Charles Bell, having decided not to run. The new board — the three incumbents and the four newly elected members — respectively met with the College Policies Committee, the department chairmen, and the administrators to discuss Dr. Strasser’s qualifications as an administrator before announcing on February 20, 1967, that it was tendering to the Acting President the position of president, the appointment to run until June 30, 1970.¹⁶ His salary was raised to $22,000, an increase of $3,500. It is interesting to note that the Board, contrary to the understanding of the previous June, did not invite other candidates to apply for the presidency. The fact that Dr. Strasser already had more than six months experience as Acting President was a decided advantage in his receiving the three-year appointment. According to him, the principal problems he faced following Dr. Hodson’s brief administration fell into five general categories:

-

The most urgent problem was to reorganize the College and to decentralize its administration so that the institution could function effectively as a multi-campus, comprehensive public community college. The organization in June, 1966, when I became [acting] president, was oriented to a one-campus concept without a sufficient number of staff to conduct its functions adequately and without staff to service the increasing community-oriented functions of the College.

-

A second major problem was to develop detailed and comprehensive long-range plans and perspectives for the expanding role of the College in the community.

-

Another problem was to provide means for the completion of the institutional self-evaluation and related processes associated with the scheduled re-accreditation visit by the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools.

-

Because of the long lead-time required for construction of College facilities, a fourth problem was to initiate promptly the planning and facilities construction necessary to accommodate the significantly increasing number of students enrolling and expected at the College.

-

Finally, extensive preparations were required for the separation of the College from the [county] school system so that the College could function relatively self-sufficiently as a major community institution.¹⁷

Meanwhile, two important studies which had been prepared by educational consultants appeared in the fall of 1966. The first was a progress report on “Enrollment Projections and Facility Requirements (Progress Report No. 1),” prepared by Odell MacConnell Associates Inc., Palo Alto, California. This report recommended that the Rockville Campus be enlarged to handle 5,000 students, that “no further renovation or remodeling of facilities occur at the Takoma Park Campus,” and that the Takoma Park Campus be abandoned for a new campus to be located “in the general area of the Beltway and the Prince Georges County line” or, if retained, the old buildings be razed and replaced with new facilities, possibly high-rise buildings if an urban campus was desired. The Palo Alto consultants also recommended that a third campus site be immediately obtained in the Germantown area and that “fourth and fifth college sites be identified and acquired.” They also thought that “a detailed county-wide master plan for junior college facility development” was needed.¹⁸ Such a master plan was developed through two studies which were respectively entitled “Long-Range Master Plan for Montgomery Junior College” and “Report on Long-Range Educational Planning for Montgomery Junior College.” The former was presented to the Board of Trustees on September 19, 1968; and the latter, in March 1969, having subsequently been adopted with modifications the following June. Regarding the “Report on Long-Range Educational Planning . . .”

In October, 1968, the President submitted to the Board of Trustees a proposal calling for the appointment of a long-range planning committee which was composed of members of the faculty, administrative staff, students, and citizens of the community, and an outside consultant; this committee was charged with the responsibility of developing a master plan of programs and services for the existing as well as any future campuses of Montgomery College, with particular attention focused on the future rehabilitation of the Takoma Park Campus.¹⁹

Expansion of the Rockville Campus, as mentioned earlier, is now taking place in order to meet an enrollment of 5000 students; and the Takoma Park Campus has been “saved”; but the nature of its future campus is at this time undetermined. Another year may bring a clear plan of design and development. While the Board of Trustees is committed to the establishment of other campuses for the College, it has not as yet purchased sites in the Germantown area or elsewhere.

In December of 1966 the second study prepared by educational consultants for the College during that fall appeared. It was entitled “Management-Administrative Study of Montgomery Junior College” and was prepared by The Associated Consultants in Education, Inc., Tallahassee, Florida. This report of 156 pages contained many recommendations including an administrative structure composed of a president and four deans (executive, faculty, students, and business management), who would report directly to the president. In turn, a dean of instruction on each campus would be responsible to the Dean of Faculty; and the campus business managers would answer to the Dean of Business Management. The Directors of Students on each campus would have as their immediate superior the Dean of Students. Moreover, the Study called for an “increase in administrative personnel to make possible planning and procedural development.”²⁰ The report recommended “. . . that a Divisional structure be used to replace the Department structure that is presently growing without limit.”²¹ The four divisions proposed for each campus were Humanities, Social Sciences, Mathematics & Natural Sciences, and Occupational Programs. Noting that “size can become a president’s nemesis unless his lines of communication to and from the teaching faculty are well defined and used,”²² the consultants believed that the division head was the key to successful communication. They found the faculty committee structure unsatisfactory because it was not well adapted to a two-campus operation and was time consuming as well as cumbersome. “There should be,” the consultants emphasized, “relatively few standing committees.”²³ Furthermore, they called for the elimination of the College Policies Committee as they did not like the committee structure “controlled” by CPC. Instead, they recommended the establishment of a faculty senate “with representatives from each campus constituting a ‘Campus Senate.'”²⁴ The Faculty Senate would have jurisdiction over matters relating to academic affairs, e.g., grading standards, addition and elimination of courses, and graduation requirements. In addition, the Faculty Advisory Committee the authority to advise the Dean of Faculty on such important subjects as promotions, tenure, and salaries. In the area of student activities, the consultants thought it best to continue the practice of having single varsity teams represent the College and “of having only one of each type of student publication for both campuses.”²⁵

As revised the College’s central administrative structure is now generally patterned after the recommendations made by the Tallahassee consultants. “The new system,” Dr. Strasser felt, “should give each campus an identity of its own.”²⁶ There is now a central administration of seventeen, including the President, Dean of Administration, Dean of Student Affairs, Dean of Program Development and Planning, and Executive Director of Business and Finance. In 1969 there was established at the instance of the Faculty Senate and Board of Trustees the office of Dean of the Faculty, one of the positions called for in the Study. The Senate selects three candidates for the position and the president in turn chooses one to serve a three-year term.

While the Dean of the Faculty, who is Dr. Robert Frieders, sits on the President’s Advisory Council, he is not considered by the President an administrative officer. Each campus has its own administration: a campus dean (Dr. Wayne Van Der Weele, at Rockville, and Dr. Robert W. Wiley, at Takoma Park) to whom the Associate Dean of Students, Business Manager, and Division Chairmen are responsible, and under each division chairman there are departments, the faculty having voiced strenuous objections to the Study’s recommendation in this regard. Department chairmen at the Takoma Park Campus report to two division chairmen: Humanities and Social Sciences and Mathematics and Science respectively. At the Rockville Campus, as the result of a recent administrative change, the department chairmen are directly responsible to the Academic Dean. The Faculty Senate has replaced the old College Policies Committee but has retained most of the latter’s functions and responsibilities. There is now on each campus a faculty “Campus Assembly,” similar in nature to that proposed by the Tallahassee consultants. During the past year or two, contrary to the Study’s recommendations, separate varsity soccer and basketball teams have been instituted at the Takoma Park Campus; and each campus now has its own student newspaper.

Shortly after the New Year 1967, Dr. Eileen Kuhns, the Executive Dean of the College, resigned to take a position with IBM in Washington, D.C. Then in mid-April the Dean of Faculty, Dr. George Erbstein, left to assume the presidency of Ulster County Community College in New York; and in June, Dr. Bernard Hodinko, Dean of Students, gave up his position to join the faculty at The American University where he subsequently assumed the office of Vice President for Student Affairs. So in six months time three key administrators had left Montgomery Junior College, having provided leadership and guidance during the previous two difficult years. Of the ten college (central) administrators during 1967–68, five had held their positions for only the past year or two. Under these conditions and with each campus now having its own set of administrators, it is not at all surprising that problems, irritating and divisive, arose.

† † †

In 1965, the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools was scheduled to send an evaluation team to the College because ten years had elapsed since the institution’s accreditation had been reaffirmed. However, Dean Deyo’s departure in the early months of 1965 and Dr. Hodson’s subsequent appointment as president necessitated a postponement of the visitation. Then Dr. Hodson’s resignation followed by Dr. Strasser’s appointment, first as acting and later as permanent president, caused yet another delay in the required visitation by Middle States. It was not until the last week in March 1968, that the evaluation team, under the chairmanship of Dr. Lawrence L. Jarvie, President of the Fashion Institute of Technology, made its appearance on the two campuses, Dr. Strasser having meanwhile submitted a “Self-Study Report” of nearly 350 pages. Some eleven committees, involving both administrators and faculty, were involved in its preparation. The Report contained not only recommendations for institutional improvement, but commendations on a variety of accomplishments and results, e.g., the low faculty turnover rate, the consistent increase in the entering salary from 1962 to 1967, the offering of “a developmental program in reading” for those who need it, well-selected book collections at both campus libraries, the general excellence of the transfer programs, and the significant contribution of the athletic program to the stated objectives of the college.²⁷

In turn, the evaluation committee commended the administration for having “moved courageously and vigorously, perhaps too much so, into a confused and dynamic changing situation.” It found that the “planned additions to the Rockville Campus are sound in view of the proposed increase in enrollment at this campus” and noted that “future planning should incorporate facilities for more technical programs if this campus is to function as a comprehensive community college.” The evaluation committee noted that the basic administration of the College was neither centralized nor decentralized and it felt that this was “a key to many of the administrative problems” confronting the institution. It was the opinion of the committee “that decentralization and greater autonomy for each campus should be the direction in which to move.” While regarding the faculty as “an enthusiastic, energetic, and well-prepared group,” the Middle States evaluators could not avoid commenting on “a noticeable existence of tension between the faculty and the administration. Some of the causes may reside in a faculty not yet initiated in the self-government which a new and extensive faculty committee system now makes possible. [As the faculty had had self-government since 1960 and faculty committees had existed since the College’s salad days, the comment is of dubious merit.] and in a young and hard-driving president.” It was the conclusive judgment of the evaluation committee that “the two things that are most immediately apparent at Montgomery Junior College is that students are learning and the faculty is teaching. Add to learning and teaching the single word quality — that is Montgomery Junior College, despite problems and tensions. The latter are not unusual, whereas quality frequently is.”²⁸ To no one’s surprise, MJC’s Middle States accreditation was reaffirmed without a request for progress reports, which, as it may be recalled, were required following the 1955 visitation.

At about the time of the evaluation committee’s visit to the College in the spring of 1968, Senate Bill No. 2, which Senator Royal Hart of Prince Georges County had introduced in the Maryland General Assembly, was enacted. This measure, which Governor Spiro T. Agnew subsequently signed into law, provided for the establishment of a State Board for Community Colleges and for separate boards of trustees for the community colleges. These local boards of education, wishing to divest themselves of their dual responsibilities, request the governor to appoint trustees whose sole responsibility would be for the two-year institutions.

In 1961 an enabling act, giving a legal foundation to the State’s community colleges, had provided that the boards of education of the counties and Baltimore City would serve as the boards of trustees of these colleges, thus giving them a legal status enjoyed by the local institutions of higher education.²⁹ For more than a dozen years community colleges in Maryland had been established and operated on the basis of an opinion by the Attorney General. Consequently the 1961 legislation gave a statutory underpinning to the community colleges which were growing in numbers and enrollments. By 1966, five years after the passage of the community college enabling legislation, it had become apparent, particularly with regard to the large counties, that a dual responsibility for a public school system and a fast-growing community college was much too heavy a burden for a local board of education to bear.

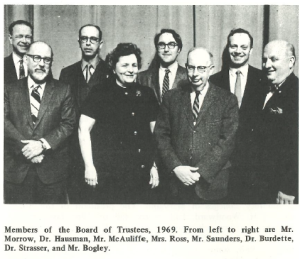

Royal Hart’s Senate Bill No. 2 had the support of both the MJC Faculty Senate and the College’s Chapter of the American Association of University Professors but not that of the institution’s president who was opposed to the discontinuation of the State Department of Education’s responsibility for community colleges. The Hart Bill aimed to do three things: free local boards of education of a heavy responsibility, if they so wished; free the community colleges from submergence in the public school systems; and free the State Department of Education from its responsibility for the two-year institutions by the establishment of a State Board for Community Colleges. As early as 1963 the Allied Civic Group of Montgomery County had proposed that the control of the College be turned over to a five-member county board of higher education and thus relieve the Board of Education from its dual responsibilities.³⁰ Three years later, the MJC Board of Trustees, by a four to three vote, adopted a resolution endorsing a report of the Governor’s Advisory Council on Higher Education calling for autonomy of the community colleges of Maryland. The president of the Board, Everett H. Woodward, had in the fall of 1965 favored such independence in a debate with Dr. Clifford K. Beck, also a member of the Board, at a Saturday morning faculty meeting.³¹ In the fall of 1968, some months after the enactment of Senate Bill No. 2, the Montgomery County Board of Education called upon Governor Agnew to appoint a separate board of trustees for the College. An editorial in The Spur asked that the people appointed to the new board “won’t look with closed minds at new ideas.”³² Governor Agnew complied with the Board of Education’s request and shortly before he left the governorship to become Vice President of the United States he appointed: Richard L. Bogley, Dr. Franklin L. Burdette, Dr. Howard J. Hausman, James S. McAuliffe, Jr., Robert E. Morrow, and Mrs. Sherman Ross. As the law provided, the seventh member, Charles B. Saunders, Jr., was elected from the Board of Education to serve a one-year term. The news of the appointments to the new board of trustees was in general well received by the faculty and staff. The College, at last, had its own board whose time and talents would not be shared with the ever-growing public school system. The appointees presented a diversity of backgrounds and experience: Mr. Bogley, an alumnus of the College, a service foreman for the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company; Dr. Burdette, a professor of political science and director of the Bureau of Governmental Research, University of Maryland; Dr. Howard J. Hausman, the head of the Student and Curriculum Improvement Section, National Science Foundation; James S. McAuliffe, Jr., a graduate of MJC, a former member of the Maryland General Assembly, and a partner in the law firm of Heeney, McAuliffe and McAuliffe; Robert E. Morrow, general manager Greenbelt Consumer Services, Inc. and vice president of Checchi and Company; and Mrs. Sherman Ross, at one time a member of the faculties of Bucknell University and Hunter College and, more recently, an officer in the American Association of University Women and the local PTA. Charles B. Saunders, Jr., the member from the Board of Education, was then assistant to the president of the Brookings Institution. Upon organizing, the Board of Trustees elected as chairman and vice chairman, respectively, Robert Morrow and James McAuliffe. The new board, having taken office in January 1969, was confronted with several problems, not the least of which was the review and approval of the College’s proposed budget for the fiscal year 1970 before it was submitted a few months later to the County Council.

One of the final acts of the Montgomery County Board of Education acting as the College’s Board of Trustees was to provide for the renaming of the institution. Effective on July 1, 1969, it was to be known as “Montgomery College” except in legal matters where the name “Montgomery Community College” was to be used in compliance with state law. Eight years before, the College Policies Committee had forwarded through Dean Deyo and with his approval “a recommendation to the Board of Education concerning the changing of the institution’s name to Montgomery College.”³³ Both students and faculty had come to feel that the word “junior” should be eliminated from the College’s name because “many uninformed citizens equate a ‘junior college’ with a ‘junior high school’ as being an institution prior to, rather than equivalent to the real thing, college or high school respectively.”³⁴ However, the superintendent and the Board of Education at the time took no action on the CPC’s recommendation. Then in September 1968, the Community Advisory Committee’s “Long-Range Master Plan for Montgomery Junior College” was published, the Committee, whose chairman was Robert E. Morrow, having been authorized by the Board of Trustees in July 1967. The Committee believed “that the name Montgomery College is both dignified and properly descriptive. Elimination of the words ‘Junior’ or ‘Community’ has ample precedent around the country (‘Community’ has much the same connotation as the word ‘Junior’).”³⁵ This recommendation from a distinguished group of Montgomery County citizens provided the necessary impetus for amending the College’s name.

Upon assuming office the new Board of Trustees was confronted with the necessity of not only passing upon the budget for the fiscal year 1970 but of dealing with the very strained relations between the faculty and the administration which had been building up for quite some time. In the spring of 1967 the College’s Chapter of the American Association of University Professors adopted a resolution deploring “the lack of administrative understanding of the role of the faculty in the formulation of policy.”36 During the following summer the administration prepared some new personnel regulations dealing with the faculty, one of which stated that an instructor was to spend an average of five hours a day and at least 25 hours a week on campus. The faculty was indignant at the imposition of such a “managerial,” unprofessional regulation, especially since it had not been consulted. Eventually the matter was quietly dropped, the faculty and the AAUP Chapter having voiced their objections. Unfortunately the year 1967–68 saw no lessening in the disagreements and irritations between the administration and the faculty. In November 1968, the Faculty Senate censured Dr. Strasser as a result of his absence from a Senate meeting and for “a general lack of communication.”³⁷ Later, the Senate rescinded the censure, having learned why the president had been unable to attend the meeting. By the time the new Board was installed, there was a general feeling among the faculty that the President failed to understand or accept the concept of faculty involvement in the governance of the institution. A climax was reached when a petition was signed by 169 full-time members of the faculty (more than 70%) requesting the Board of Trustees to consult with the faculty concerning Dr. Strasser’s reappointment or the appointment of a successor.³⁸ Inasmuch as the faculty had been consulted at the time of Dr. Hodson’s appointment, this constituted a precedent for this request. However, the underlying reason for the petition was obviously an expression of dissatisfaction with the administration, at least for many, if not most, of the signers. This action prompted the new Board to discuss the matter with the Faculty Senate and with the department chairmen on both campuses. The Board then decided to reappoint the president to serve at its pleasure, which is the customary arrangement between college and university presidents and their boards of trustees. During 1969–70, tensions between the administration and the faculty appeared to have lessened.

Meanwhile, responding to a request from the author, Dr. Strasser noted with pride in a memorandum, which was distributed to other administrative officers, past and present members of the Board of Trustees, the chairman of the Faculty Senate, and former President Hodson, some fourteen accomplishments made during his administration.³⁹ Among them were:

“A greatly broadened base of participation by faculty, staff, students, and the community in the formulation of College policies and in the creative responses of the College to the community . . .”

“Considerable diversification of the programs and services of the College, including many new degree curricula and courses, a certificate program, non-credit community service courses and programs . . .”

“Major rapid expansion of the number of full-time positions of the College for multi-campus operation, including faculty, supporting services personnel, and administrators (the number of full-time positions in June 1966 [when Dr. Strasser became Acting President] was 227, while the number of full-time positions approved by the Board now for September 1970 is 633, an increase of about 180% in four years, while enrollment increased about 110% in the same time);”

“The development of an effective multi-campus organizational structure to serve each campus and the College system as a whole;”

“A significant expansion in the relationship of the College to the community, through many new community advisory committees, the establishment of a full-time public information office for the College, the initiation by Montgomery College of the new state-wide ‘Community College Week,’ and extensive use of College facilities by the community . . .”

“The reaccreditation of the College in 1968, during a period of rapid growth, stress, and change within the College;”

“The initiation of a major construction program for the College, including the funding of various minor construction projects and eight new buildings or additions on the Rockville Campus, the planning for the redevelopment of the Takoma Park Campus, and the funding of site acquisition for two additional campuses for the College;”

“The substantial separation of the College from the school system in 1967 and the appointment of a separate Board of Trustees for the College in 1969, including during that time a new name for the College . . .”

“Major improvements in college salary schedules and actual salaries paid faculty, supporting services personnel, and administrators, through such means as new salary schedule concepts and a new position classification plan for supporting services personnel” and

“Greatly expanded opportunities for the professional development of faculty and staff, through major increases in funds for sabbaticals, travel to conferences, consultants, various leave policies, and a tuition-waiver program.”

While the President could take justifiable pride for the accomplishments he listed, the faculty, staff, and Board of Trustees, he also recognized, shared in their realization.

“Hard-working,” “tough-minded,” “careful,” and “bright,” the College’s second president has also been described as “exceedingly ambitious,” “clinical,” “cold,” and “organizationally obsessed.” Few positions today are more difficult and demanding than that of a college or university president. Pressures from the student body, faculty, board of trustees, and the public, stemming in part from the uncertainty of the times, are constantly on the head of an institution.⁴⁰ And the president of Montgomery College has been no exception to this general situation. Coming to the presidency in 1966, Dr. Strasser was faced with a difficult situation for which his limited collegiate experience was a handicap. A young man in a hurry, he was anxious to restructure the College and to enlarge its scope of operation. It is not surprising that he met with resistance from time to time from others who felt that they, too, knew what was best for the institution.

Yet despite the differences and, at times, outright clashes between the administration and the faculty, the College has grown in enrollment, instructional staff, and programs during the past four years. More than 8000 students, taught by a faculty of over 500, are expected to enroll in the fall of 1970 when the College commences its 25th year, a striking contrast to the size of the student body and faculty that met in the fall of 1946, at the Bethesda Chevy-Chase High School.

- John W. McLeod, FAIA, Washington, D.C., letter, 31 March 1970, to the author.

- Between 1957 and 1959, Dr. Hodinko was a counselor at MJC. Prior to his return to the College in 1965, he was an administrator at the University of Maryland. He is presently Vice President for Student Life at The American University, Washington, D.C.

- George Hodson, President, North Country Community College, Saranac Lake, New York, letter, 30 Oct. 1969, to the author.

- Ibid., Lander, pp. 74-75.

- Lander, p. 53.

- William L. Fox, Takoma Park, Md., letter, 28 June 1962, to James S. McAuliffe.

- James S. McAuliffe, Rockville, Md., letter, 29 June 1962, to the author.

- The Nursing Curriculum began in the fall of 1966 under the direction of Miss Helen A. Stafis. A student undertaking this program may receive the A.A. degree by attending two years and one summer session and the R.N. license after taking the State Board examination following graduation. By the end of the 1970 summer session, 48 students had graduated from this program.

- General Survey of the College Athletic Program, May, 1963 (mimeographed report), p. 1, Montgomery College Records.

- Louis G. Chacos, Professor of Physical Education, Montgomery College, Rockville, Md., telephone interview with the author, Spring, 1970.

- William P. Fidler, “The Expanding Role of the Community College in Higher Education,” December 11, 1965 (mimeographed), Montgomery College Records.

- Justus Hanks, Professor of History, Montgomery College, Rockville, Md., memorandum, 19 April 1970, to the author.

- Dr. Hodson is now president of North Country Community College, Saranac Lake, New York.

- George Hodson, Saranac Lake, N.Y., letter, 30 Oct. 1969, to the author.

- Everett H. Woodward, Silver Spring, Md., letter, 16 July 1970, to the author. Everett H. Woodward, telephone interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 10 Aug. 1970. Mr. Woodward was president of the Board of Trustees (Board of Education) at the time Dr. Strasser was made Acting President.

- The Spur, 2 March 1967.

- William C. Strasser, Rockville, Md., mimeographed memorandum, 16 Feb. 1970, to the author.

- Odell MacConnell Associates, Inc., A Progress Report to the Board of Trustees, Montgomery Junior College, Rockville, Maryland, 19 Sept. 1966, p. 8, Montgomery College Records.

- Eric N. Labouvie, Dean of Program Development and Planning, Montgomery College “Annual Report, 1968-69,” p. 1, Montgomery College Records.

- The Associated Consultants in Education, Inc., “Management-Administrative Study of Montgomery Junior College,” p. 156, Montgomery College Records. (cf. Mr. Strasser’s first category of problems as mentioned on p. 79.)

- Ibid., p. 15.

- Ibid., p. 125.

- Ibid., p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 102.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- The Spur, 16 Feb. 1967.

- “Self-Study Report,” Montgomery Junior College, submitted for consideration by the Commission on Institutions of Higher Education of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, January, 1968, passim, Montgomery College Records.

- Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, Commission on Institutions of Higher Education, “Evaluation Report,” March 24–27, 1968, Montgomery College Records.

- Chapter 454, Acts of 1968, Annotated Code of Maryland.

- Knights’ Quest, 11 April 1963.

- Lander, p. 79. Everett H. Woodward, Silver Spring, Md., letter, 16 July 1970, to the author.

- The Spur, 21 Nov. 1968.

- William L. Fox, Takoma Park, Md., letter, 26 Oct. 1961, to Dr. C. Taylor Whittier, Superintendent, Montgomery County Public Schools.

- Ms. Ruth J. Smock, Takoma Park, Md., memorandum, 27 March 1962, to Superintendent’s Committee on Higher Education.

- Community Advisory Committee, “Long-Range Master Plan for Montgomery Junior College,” September 19, 1968, p. 10, Montgomery College Records.

- The Spur, 13 April 1967.

- Faculty Senate Minutes, 14 Nov. 1967. Montgomery County Sentinel, 27 Feb. 1969.

- Montgomery County Sentinel, 27 Feb. 1969.

- William C. Strasser, Rockville, Md., memorandum, 16 Feb. 1970, to the author.

- “There are at present several hundred presidential vacancies in our colleges and universities.” Dr. Alfred D. Sumberg, Associate Secretary, American Association of University Professors, Washington, D.C., personal interview with the author.

Media Attributions

- Rockville Campus from Above, Fall 1969

- Tip-Off at Rockville

- Board of Trustees, 1969

- Early Musical Production of Der Fledermaus

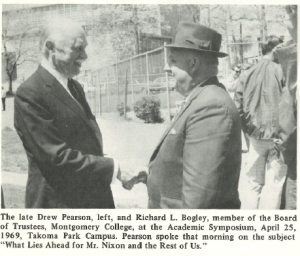

- Drew Pearson at the 1969 Academic Symposium