TAKOMA PARK:

A DECADE AND A HALF

(1950–65)

When in the late summer of 1950 Montgomery Junior College moved from Bethesda to Takoma Park, it was entering a community which had been established in 1883 by Benjamin Franklin Gilbert (1841–1907), a Washington realtor. Mr. Gilbert conceived of Takoma Park as a homogeneous suburb which would afford “… family homesites away from the stagnant canals and marshy sea-level pestilence of crowded Washington.” He rightly figured that the great development of the Capital would follow a general northern expansion along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Seventh Street Pike and Fourteenth Street.¹ The founder of Takoma Park purchased 900-odd acres embracing land on both sides of the District of Columbia–Maryland line along the Metropolitan Division of the B & O. “This tract formed the central section of Takoma Park … high, healthful, wooded privacy, in close communication with the city of Washington. The subdivision was the first of 14 which now comprise the town.”²

In the early ’90’s, Gilbert built the North Takoma Hotel, a 160-room hostelry on the site of the present Administration Building on the College’s Takoma Park campus. This was one of three hotels built in the town. In 1906, a girls’ finishing school leased the North Takoma Hotel but found that it had an inadequate heating system; so the plant lay idle for a year.³ Then in 1908 Professor Louis D. Bliss purchased the defunct hotel and the six to seven acres which went with it for his electrical school located at that time in downtown Washington at 219 G Street, Northwest.

Fifteen years before Bliss bought the Takoma Hotel, he had started his school at night with twenty students and $200 capital.⁴ According to the school’s Announcement for 1896–97:

The Bliss School of Electricity, Incorporated … is the only Institution in the country where Practical Electrical Engineering is exclusively taught, offering to students a complete course in one year. To meet the rapidly increasing demand for men trained in the technology of the Art, this School was created. Its name indicates its purpose. It is a workshop for practice in everything connected with electricity.⁵

The one-year program, which MJC absorbed when it moved on to the Bliss campus, was designed for the practical electrician. Bliss felt there were three classes of workers in electricity: the “do-all” electrician who knows little or nothing about the principles of science; the practical electrician who is trained in both theory and practice and who is or ought to be “a master of electricity” and the university graduate who is generally a consulting engineer.⁶ The second was the one which the Bliss Electrical School undertook to train.

It was on November 6, 1908, not long after Bliss had moved the school into its new quarters in Takoma Park, that the building burned to the ground. Apparently the only thing which was saved was his lecture notes. The disastrous fire put the school in the red by $100,000. However, “the neighborliness of the townspeople was demonstrated on this occasion when they clothed, fed and housed the school’s students until permanent arrangements could be made.”⁷ Bliss wasted no time in making arrangements for a new building, the first wing of which was completed a year later. Within the next few years the second addition was added to what is now the Administration Building, and in 1917 the Dining Hall (present Student Building) and the dormitory (now the Academic Building) were completed.

On October 27, 1950, 57 years after the renowned technical institute had been founded, the last commencement exercises of the Bliss Electrical School were held. About 12,000 young men had gone through the Bliss program, many of them having taken positions in such companies as General Electric, Westinghouse, Western Electric, RCA, and Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone. While the last Bliss class was completing its work, MJC moved on to the campus. So there was a brief overlapping between the beginning of the College’s fall semester and the completion of the Bliss operation.

At the final commencement, the opening hymn of which was the plaintive melody “I Need Thee Every Hour,” Dean Price told the graduates that he could “… see no reason why Professor Bliss and the Alumni Association should feel heavy hearted today.” “After all,” he added: “There is a deep sense of accomplishment. What you keep is lost; what you give is forever yours.”⁸

The summer of 1950 was a difficult time for the College which was involved with the demands and frustrations of moving on to a permanent campus and for the nation which was drawn into war in defense of South Korea. Lee L. Ehrbright, who had recently been appointed to the new post of Assistant to the Dean, did much of the planning work necessary to the move. He had formerly been the Dean of Students at Walter Hervey Junior College in New York. During his fifteen years of service at MJC, however, his duties were chiefly centered in fiscal affairs.

One of the unfortunate consequences of the move from Bethesda was the loss of about 900 of the library’s volumes as the result of water damage caused by a heavy rain which sent water pouring into the basement of BCC where cartons of books sat waiting to be trucked to the Takoma Park campus. For this heavy loss the College ultimately received $3,000 from its insurance, but some of the damaged volumes had meanwhile gone out of print and so could not be replaced.⁹

Not only were there problems in moving books, instruments, laboratory equipment, and office furniture (most of which was war surplus) but also in making certain renovations of the Takoma Park campus such as providing for classrooms in the old dormitory by knocking out some of the non-supporting walls. There was even a problem of who should first receive mail addressed to the Bliss Electrical School, Dean Price or Professor Bliss. Price felt that it should come to him since MJC now had possession of the Takoma Park campus; Bliss objected inasmuch as the mail was addressed to BES and not to the College.¹⁰ But, meanwhile, MJC’s administration and faculty had received some good advice from consultants who had come to Takoma Park for a two-day conference.

With purchase of the Bliss Electrical School by the Montgomery County Board of Education, it was the belief of the State Superintendent of Schools, Dr. Thomas G. Pullen, Jr., that some long-term planning should be entered into covering the program of Montgomery Junior College and its relationships to the other junior colleges and higher education programs in the State of Maryland.¹¹

On August 17-18, a committee of consultants composed of Dr. Lawrence L. Bethel, Director, New Haven Y.M.C.A. Junior College; Dr. Henry W. Littlefield, Vice-President, University of Bridgeport; and Dr. Dwayne Orton, Director of Education, International Business Machines, met with members of the MJC staff, Dr. Edwin W. Broome, Superintendent of Montgomery County Public Schools, and Dr. Wilbur Devilbiss, Maryland Supervisor of Junior Colleges and Teachers Colleges, to examine the institution’s program and to make recommendations concerning curriculum, students, faculty and staff, plant, community relations, and finance. While the consultants were concerned with the possibility that the absorption of the Bliss program “might have a narrowing influence on the College as a whole,” they nevertheless recommended its retention but only as “a transitional and experimental procedure.”¹² They urged that this program be made into a two-year curriculum similar in nature to the other terminal programs. Four years later a two-year Electrical Technology curriculum was inaugurated.¹³ Among the other recommendations of the committee were: the elimination of the word “terminal” in curricular designation in the catalog, which was subsequently done; the desirability of year-around operation; the addition of short courses for adults; granting of a certificate for the satisfactory completion of one-year’s work; the establishment of remedial work for those students who are unprepared; employment of a director for the technical and vocational programs and of someone to coordinate the adult education courses and such community activities as the symphony orchestra and lecture series; the question of professorial rank for instructors be left to the faculty’s discretion; renovations of the plant including the painting of the buildings and discarding “pre-ark” furniture; and the preparation of a study on the costs of community colleges in order that “a determination could be made of what is adequate for Montgomery Junior College in terms of community needs.”¹⁴ The consultants in general were quite pleased with what MJC had been able to do in four years. Writing to Dean Price two weeks after their visitation, Dr. Littlefield noted: “You and your staff deserve the highest commendation for what you have done and I am confident that in a few years you will have one of the leading junior colleges in the middle states area.”¹⁵

Due to the problems of moving and of making needed renovations to accommodate biology, chemistry, and physics laboratories and, as previously noted, additional classrooms, there was a short delay in the opening of the fall semester. Despite these problems, the College enjoyed the largest registration it had had to date—541 students—and would have until 1955. The four years following 1950 reflected enrollments of less than 500, the involvement in the Korean War and the declining birth rate of the depression years of the 1930’s undoubtedly accounting for the decrease.¹⁶

Of the nearly 550 students who enrolled that first semester on the Takoma Park campus, 80 were from out-of-town, coming from some 20 different states.¹⁷ The continuation of the Bliss program accounted for this substantial number of students who came from outside the Washington Metropolitan area. Their presence was especially felt when five electrical students were elected as freshman members of the Student Council, bringing irritation and consternation to some among the non-electrical student body.¹⁸

Within a few weeks following the beginning of classes in the fall of 1950, an incident occurred which rocked the administration and the faculty. It involved a part-time instructor and her son who were arrested in Bethesda, the son having been charged with driving without a muffler, reckless driving, and assaulting a police officer and the mother, with drunkenness and disorderly conduct. The episode was publicized, and Dean Price was asked by the Superintendent to relieve the instructor of her teaching duties until the time of her trial. The AAUP Chapter was interested in this case because the Superintendent’s action was considered a prejudgment of it.¹⁹ At a special meeting of the AAUP Chapter on October 19, to which Dean Price and non-members of the faculty were invited, a resolution was unanimously adopted calling on the Superintendent to review his action and, if possible, to rescind it. Later in the meeting, this resolution was withdrawn and a substitute was adopted calling for the Chapter to send two of its officers together with Dean Price to discuss the entire matter with Superintendent Broome and to indicate to him that his action was not looked upon with favor by the members of the Chapter nor the non-members of the faculty who were present at this meeting.²⁰ Perhaps the subsequent meeting with the Superintendent was the saving element in this case because although the instructor was later found guilty of disorderly conduct, she was reinstated as a part-time member of the MJC Faculty. This was the AAUP Chapter’s first experience in taking a firm stand on an issue, which had produced a serious disagreement between the administration and the faculty.

By the end of the fall semester, 1950-51, nearly 30 students had either left or were about to leave for the armed forces. “With these men,” editorialized the Knights’ Quest, “being examples in our minds of what is happening to the student body of America, it is difficult to understand the purpose of continuing to attend classes. Students have become dejected because there seems to be no purpose to school, no progress being made.”²¹ It is interesting to compare such a reaction as this, which was not untypical of college students’ reactions in the early 1950’s, with the militant responses of students following the escalation of the Viet Nam War.

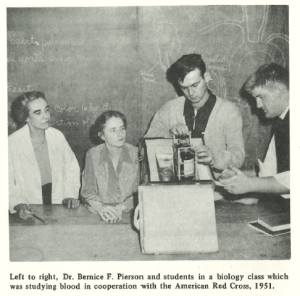

During the first year on the old Bliss campus, the College served as the meeting place of the Montgomery County Civic Federation. Moreover, the American Red Cross conducted several of its training programs on the campus as did the Takoma Park Police Department its police school. In the spring of ’51 the Maryland Convention of the American Association of University Women was held at the College and so likewise was the annual banquet of the State Convention of the League of Women Voters. For the local wing of the Civil Air Patrol the College made available some facilities, and a Link Trainer was mounted for the use of the Patrol and students of MJC. So in the area of providing a meeting place for various community activities, the institution was fulfilling one of the many functions of the developing community college.

Internally, there was established that year under the leadership of Allen H. Jones, then Chairman of the English Department, the Invitation to Discussion Program which was open to both students and faculty. This program, which was one of the most stimulating intellectual activities ever held at the College outside the classroom, centered on discussions, conducted informally, on such provocative books as Forester’s A Passage to India, Huxley’s Brave New World, and Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

With the ending of the spring semester, 1951, MJC had completed five years of operation. Believing that it was appropriate to summarize the institution’s progress, Dean Price submitted to the Superintendent early the following September his “Five-Year Report of the Dean, 1946-1951,” an interesting as well as impressive statement. Although by late May, 1946, the College had been established “there was no curriculum, no budget, a staff of one, no equipment, no campus, no buildings, no catalog, no records, and no students.²² However, five years later, as Price proudly noted, there were twenty-one curriculums, “budget in excess of $200,000, a staff of fifty instructors and office personnel, close to $300,000 worth of equipment, a six-acre campus with six buildings valued at more than $350,000, six catalogs . . . published, a comprehensive system of records under the care of a competent registrar, and 1574 students have come under the influence of the institution.”²³ Of that number 167 had received the Associate in Arts degree and 65 the one-year certificate in technical electricity. Price estimated that over 275 students had gone on to 46 different colleges and universities.

The report indicated further that the College had maintained “an aggressive program of public relations,”²⁴ which had included personal appearances by the Dean before church and civic organizations, service groups, and on radio programs. Price considered the Montgomery Junior College Advisory Council as being a valuable asset not only in providing assistance and advice but in reporting to the community the institution’s progress and “in interpreting the College to those in fiscal authority in the county. . . .”²⁵

Later in the Report, Dean Price called attention to the significant fact that the tuition and fees paid by the students and Veterans Administration had “carried a substantial part of the cost of operation as follows: 1946-47 — 66%; 1947-48 — 71%; 1948-49 — 76%; 1949-50 — 58%; and 1950-51 — 59%.” A total of student tuition and fees for the five years — $446,170 or 65% of the total cost of $667,266.²⁶ During the same period Montgomery County’s contribution for operating expenses amounted to $111,265, and the state’s donation came to $77,063.

In his conclusion Dean Price observed that any administrator of a college or university faced “an uncertain future” in which the Selective Service and U.M.T. [Universal Military Training] will cut deeply into the student’s education. On the other hand, America’s great crop of war babies is gradually approaching the junior college level of education, and as they arrive, the College will no doubt feel the impact of their presence in its enrollment.”²⁷ Price thought that within the next five to eight years MJC’s enrollment might easily double. Actually by the fall of 1957, the College’s enrollment had doubled and by 1959, eight years after the Report, had indeed more than tripled! (See Appendix A.) The Dean urged that the College prepare for the enlarged student body “and not be caught flat-footed.”²⁸ He closed his “Five-Year Report” on a positive note: “Montgomery Junior College wants to be recognized and fully accepted as Montgomery County’s Community College.”²⁹ Yet, the fulfillment of that desire was not going to be realized for at least ten years.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 1951, the Board of Education had signed a contract with the U.S. Navy Bureau of Personnel for the establishment of a Class “A” school for the training of electricians’ mates at MJC, Dean Price having handled the negotiations. This contract, which was scheduled to run for at least one year and actually was renewed for a second year, undertook to train 175 men at a time in classes of 25 that reported for duty every two weeks for a fourteen-week course.³⁰ The Navy was interested in setting up such a pilot school for the purpose of gathering data on the operation of this type of program on a college campus in the event of a national emergency. Almost 1,000 bluejackets went through this program during the two years of its operation. For the College it meant $20,000 of additional income for each of the two years and certain much needed kitchen equipment. Moreover, the Navy agreed to pay its full share for heat, light, and maintenance.

Although the Navy program did not conflict with the regular offerings and activities of the College, it was expecting too much to have two such entirely different programs run compatibly on such a small campus, especially when “open gangway,” seemed to be the disciplinary policy practiced by the Navy at MJC.³¹ This is not to say that there was constant friction between the Navy and the academic programs, but rather occasional irritation. In short, the presence of the Navy on the campus was somewhat disruptive as one of the instructors in the program has pointed out.³²

During the two years that the Navy Class “A” school was in operation, which happened to be Dean Price’s last two years at the College, selected academic courses commenced to be offered at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory at White Oak, Maryland. This was a harbinger of an extension program which some years later the College developed.

Recognizing the need for providing more scholarship aid, the Board of Education established late in 1952 seven full-tuition scholarships for county high school graduates which were to be awarded annually beginning the following September. By the fall of 1965, when the second campus opened at Rockville, 46 students were attending MJC on scholarships. Fourteen of these students were the recipients of Board of Education scholarships, the county high schools having each been represented among this number.³³ With the tremendous growth of enrollment in the early 1960’s and the opening of the new campus in 1965, there was a corresponding increase in the number of scholarships.

In the meantime, as a consequence of the Korean War, arrangements were made for MJC students to enroll in the University of Maryland’s Air Force ROTC basic program, beginning in the spring semester of 1952. On Tuesday and Thursday mornings the College provided free bus transportation to the Armory at the University. Those students in the program who transferred to Maryland for their junior year could complete the advanced ROTC program and thereby earn a commission in the Air Force. This arrangement with the ROTC unit at Maryland lasted for a little over ten years. However, during the last years while it was in effect very few MJC students were enrolled.

† † †

It was in the spring of 1953, seven years after the College had gotten underway, that Dean Price announced to a surprised faculty that he was resigning in order to accept a position as the Director of Ventura College, a public junior college at Ventura, California. By this time he had achieved national prominence in the field of junior college administration, having been recently elected vice-president of the American Association of Junior Colleges.³⁴ He was going to a California junior college which was to have ready by the fall of 1954 a new plant on a 133-acre campus for 2000 students.³⁵ Here was a further challenge for a man who had successfully pioneered Maryland’s first community college. About three years after his departure from MJC, Price resigned his position at Ventura to become a Junior College Specialist (later Chief, Bureau of Junior College Education) for the California State Department of Education.

Before the Prices left for California, the faculty honored them with a dinner at Olney Inn and a lovely silver candelabra set. Immediately following commencement they headed west. Understandably there were mixed feelings among the faculty concerning Dean Price’s departure. Some regretted very much his leaving MJC; others were more concerned about the kind of person who would be appointed his successor, especially since the appointment had not been made at the time he left.

There is today among those who served under Price a general feeling of esteem for the man and for what he had accomplished during his seven years at the College. To Mrs. Freda Malone:

Dean Price was our most dedicated-to-vision Dean. He was close to the faculty and wanted to be a part of the total activity, both in our college and in the state and national growth. His administration was a time for growing for all of us; we built together, all of us.¹³⁶

Stephen G. Wright doubts “that any of the succeeding administrators could have succeeded as well as he [Price] in meeting the original organizational problems of the college and in assembling what is regarded by many as one of the finest faculties any young college ever had.”³⁷

Dr. George S. Morrison, a member of the faculty from 1948 to 1958, feels that the most significant contribution which Dean Price made to the College was his method of establishing the faculty organization.

Although nobody will probably ever know the extent to which he intended the faculty to “take over” the institution, the fact remains that he did set up and encourage a system of faculty committees which did, through the observance of the spirit of parliamentary procedures, give the faculty a very strong voice in academic policies. I think that this fact along with the fact that he did insist on hiring qualified faculty members, accounts to a great extent for the strong academic reputation that MJC was able to earn with surrounding four-year institutions.³⁸

F. Frank Rubini, who was Director of Athletics, Health and Physical Education and Head Football Coach for nearly eleven years and who was closely associated with Dean Price, thinks that the man was perhaps “more of an administrator and promoter than the educator, but I believe this is what was necessary in the incubation period for any new institution. He did marvels with the money on hand. He selected the best instructors for the job. He knew his way around with the administration and the politicians.”³⁹

Probably Dean Price’s principal limitation as a college administrator stemmed from his experience as a teacher and administrator in a small, private, preparatory school which may have resulted in an instinctive desire to keep a direct control on all institutional matters. He found it difficult to delegate authority.

Nevertheless, when Hugh Price’s administrative virtues and limitations are carefully weighed, one must conclude that he was “the right man at the right time.”⁴⁰

† † †

By the time that Dean Price resigned his position at MJC, the Faculty Workshop following commencement had become customary, and all full-time members of the faculty were expected to attend. The workshop — a term which some of the instructors came to detest — which was held in June 1953, was particularly significant because it was completely organized and conducted by the faculty for the purpose of preparing a report for the information and benefit of the new administrator, whoever he might be.⁴¹ More than a dozen recommendations were contained in this report, clearly revealing the particular concerns of the faculty.

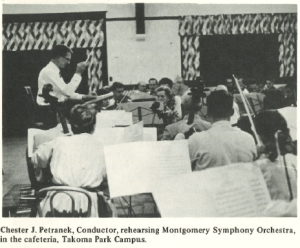

No student, the faculty recommended, should be allowed to take any course for which he was inadequately prepared or for which he was obviously not qualified. Criteria for admission to any course was to be developed by the department concerned in cooperation with the Curriculum Committee. Moreover, it was proposed that introductory courses be established for students who failed to qualify for admission to regular courses so that they could make up their deficiencies, should they desire to do so. The faculty recognized the need for additional terminal and vocational courses, suggesting that such courses as Home Economics and Child Care be offered as a means of attracting more women in the community. The whole policy of admissions, it was urged, should be carefully reviewed. “The faculty recommends that the most important criteria for admission should become the availability of courses appropriate to the student’s needs, regardless of the curriculum in which he is entered.”⁴² And with reference to admissions, it was felt that someone other than the Dean should be Director of Admissions to whom the admissions committee ought to be established. Concern was expressed for the need of a standard policy concerning student absences which, it was agreed, was to be reported daily to the Student Personnel Office so that immediate action could be taken. The report emphasized the importance of bringing to the public’s attention through advertising the opportunities MJC offered, and it was felt that for the evening program adult education classes should be instituted for the non-degree students. A public relations director was recommended as was a coordinator of student activities who would have responsibility for the entire extra-curricular program. The Montgomery County Symphony Orchestra, the faculty agreed, should be continued with the hope that outdoor concerts on the campus in the fall and spring might be arranged. (The conductor never agreed to this because there was no shell for the orchestra.) The necessity for a faculty handbook which would clearly set forth the duties and responsibilities of individual instructors and the faculty in order to insure a greater uniformity was yet another recommendation. A first aid station, a physician on call, a team physician, and a part-time nurse were among the recommendations dealing with student health. In the area of communications, it was urged that telephones be placed in faculty offices as the telephone service was quite inadequate for conducting college business. And since faculty expenses for required attendance at professional meetings and conferences had been borne by the teachers, it was felt that henceforth the College should pay all or part of them.

Many, if not most, of these recommendations were ultimately adopted over a period of a dozen years, in some instances only as the result of repeated requests by the faculty. In 1962, a faculty handbook was finally published by a faculty committee. But it was not until 1965 that a significant improvement in telephone service was achieved. Within a year or two following the Faculty Report on Policy Recommendations the College commenced to meet up to one-half of the travel expenses of full-time instructors attending professional meetings. By March of 1954, Dean Price’s successor, Donald E. Deyo, was ready to respond to the recommendations made in the Faculty Report. “He said that curricula for women, long outnumbered at MJC, were being explored, including nursing, education, nursery education and institutional food service management. Terminal curricula in building construction, industrial management, drafting and design, accounting and dental technology were being considered.”⁴³ The electronics curriculum was being converted to a two-year program, and evening courses were being introduced in order to broaden the terminal offerings. Moreover, “efforts were being made to publicly advertise evening courses.”⁴⁴

In the summer of 1953, Dr. Forbes H. Norris became the new superintendent of the Montgomery County Public Schools following the retirement of Dr. Edwin W. Broome who had seen the county schools evolve from a small, undistinguished system to a large one of increasing size claiming national attention. One of Dr. Norris’s first duties was to appoint as the new Dean of Montgomery Junior College, Donald E. Deyo, on the recommendation of, among others, Dr. Jesse P. Bogue, Executive Secretary of the American Association of Junior Colleges.⁴⁵ Born and reared in Kewanee, Illinois, Dean Deyo was forty years old when he came to MJC. His credentials included a bachelor’s degree from what is now Southern Illinois University, an M.A. in economics from the University of Michigan, and an M.A. in education from Teachers College, Columbia University.

Between 1939 and 1943, he had served as head of the business administration department and as bursar at Hillyer Junior College in Hartford, Connecticut. For the next seven years he was associated with Walter Hervey Junior College in New York as the director, and for the three years prior to his coming to MJC he was the editorial director of the junior college program of John Wiley & Sons, Publishers. “I’ve heard it said,” Miss Sadie Higgins has recently recalled, “that at the time he came to us Dean Deyo was one of a few men in the country who probably had read the whole body of knowledge on community colleges at that time.”⁴⁶

Dean Deyo’s first year at the College was uneventful. There were no serious problems and no strains between the faculty and the administration. One faculty member wrote admiringly: “Mr. Deyo is the kind of administrator to whom you can talk honestly and forthrightly.”⁴⁷ He “. . . seemed to bring to the campus a sense of business know-how.”⁴⁸ Perhaps Dr. Morrison was correct in his assessment of Deyo and his administrative style when he wrote:

I think that Deyo was a more objective administrator and less sensitive to criticism than was Price.

My impression was that he would have been much happier to deal with the faculty on an informal person-to-person or person-to-group relationship, rather than to deal with a parliamentary structure of committees.⁴⁹

The transition between administrations was relatively smooth. “There may have been some differences,” former Dean Deyo has noted, “in detailed administrative practices based on differing personalities and on Hugh’s physical handicaps which made it difficult for him to move about physically. But conceptually and philosophically, I think we were in close agreement.”⁵⁰

In 1954–55, during Dean Deyo’s second year, the College offered for the first time a course in Directed Reading for sophomores. Students who elected this two-semester course read “. . . selected books under the guidance of an interdepartmental committee of the faculty.”⁵¹ Oral and written reports on the readings were required at the five 75-minute sessions during the semester. The course was withdrawn after one year by Dean Deyo when objections arose that it was not being included as a part of the teaching load of the faculty members involved as had been insisted upon when the faculty approved it. Some years later – in the early 1960’s – the Great Books and honors courses were instituted, the Directed Reading course having served as a short-lived precedent.

The major event which occurred during the second year of Dean Deyo’s administration was the visitation of a Middle States evaluation committee for the purpose of reaccreditation. Usually such visitations come every ten years, but the Commission on Institutions of Higher Education of the Middle States Association wished to see what the College had done in the five years following its initial accreditation, especially with regard to securing a campus and plant of its own. Prior to the evaluation committee’s appearance early in March, 1955, Dean Deyo stated quite confidently on one or two occasions that there was nothing to worry about concerning reaccreditation. Although the institution was reaccredited, the Dean of the College was required to file two progress reports with the Commission, dealing with the suggestions made by the evaluation committee.

The evaluation committee whose chairman was President Eugene S. Farley of Wilkes College, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, found fault with several things about the College. The committee was critical of the meager library budgets of 1953–54 and 1954–55. It expressed concern for the impressive loss (at least two-thirds) of students between the freshman and sophomore years, and it also noted the small percentage of women students. “. . . In spite of reported parents’ and students’ preferences for transfer programs,” the committee felt, “steps need to be taken to accommodate students of low ability and aptitude only in terminal programs.”⁵² The committee concluded that the College needed a community-wide survey in order to find out what the curricular and vocational needs of the county were as it was felt that the institution’s terminal offerings were much too limited. To several of the faculty at that time, it seemed that “the evaluators paid scant attention to an area where the College had done an effective piece of work; namely the transfer curricula.”⁵³ The committee noted that the lack of funds made it difficult for the College to “accomplish its present purposes and resources even in part” and that it was then “. . . ill prepared to meet the challenges of the next fifteen years, explicit in available statistics dealing with present and future enrollment in the various Montgomery County Schools.”⁵⁴

Just a few days before the Middle States evaluation committee made its appearance on the Takoma Park campus, the “Report of the Committee to Study the Junior Colleges”⁵⁵ was published. This was a study by a committee of laymen who had been appointed by the Board of Education for the purpose of making recommendations on the place of MJC and Carver Junior College in the public school system. Under the chairmanship of Thomas A. Jackson, the committee presented a report which was, in some areas, at variance with the Middle States Report. The Jackson Committee, as it came to be called, was satisfied that no change should be made in the present status of the junior college as part of the county system of education.⁵⁶ It was satisfied that MJC was “fulfilling its objectives in both the transfer and terminal programs” and that Carver Junior College was administering and fulfilling its objectives. Contrary to former Dean Price’s desire and hope, the committee felt that it was unnecessary for the county to provide free tuition to junior college students. Moreover, the committee concluded that there should be a definite limit to the size of the institution’s enrollment. “One of the major advantages of the Junior College is that it is small, enabling its faculty to give close personal guidance and attention to the students.”⁵⁷ The committee felt that “there should be an affirmative policy that Montgomery Junior College should remain small, probably with 1,000 students as a ceiling. When that number of students is reached, the number of students from the District of Columbia and other states than Maryland should be reduced by a policy of greater selectivity.”⁵⁸ As the College’s enrollment expanded in the 60’s, such restrictions were employed. The Jackson Committee could find no “present justification for the consideration of a new site for Montgomery Junior College,” believing that the Takoma Park campus “while not ideal in many respects, is adequate for a number of years to come.”⁵⁹ Ten years later to be exact, the College opened a second campus at Rockville, having run out of space at Takoma Park. Finally, the Jackson Committee felt that there was justification for the construction of a field house, which in 1970, the Takoma Park campus still lacks; and it further recommended that the Board of Education should make arrangements with the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission for the use of neighboring Jessup Blair Park for the College’s physical education program and varsity sports. As one can readily see, the Report of the Jackson Committee was essentially conservative in its evaluation and recommendations.

During 1955–56, the year following the Middle States’ and Jackson Committee’s Reports, a very interesting series of lectures were held at the College on the religious theme “What I Believe.” It began with lectures which embraced the Judeo-Christian tradition, began with Judaism, continued with Roman Catholicism, Presbyterianism, Episcopalianism, Unitarianism, the beliefs of the Religious Society of Friends, and concluded with Seventh Day Adventism, the most recently established denomination covered in the series and one closely associated with Takoma Park. With the exception of the Friends, each denomination was represented by a clergyman from Montgomery County. This program was but one among several examples of the College making use of community talents and resources.

† † †

Commencement week, June, 1956, marked the end of the tenth year of operation for MJC. During the week an alumni dinner was held on campus, and the author was invited to give the after-dinner address, which was entitled “The First Ten Years and After — At Montgomery Junior College.” The speaker noted that during Dean Deyo’s first three years, the buildings and grounds were improved and made more attractive; and the College, fiscally and in some other respects, was brought closer to the Montgomery County Public Schools. Later in the address the speaker called attention to the fact that

The faculty has been fortunate in not having the administration or any groups in the community trespass on its academic freedom. This is especially significant when one recognizes that we have been passing through a period [of McCarthyism] when there have been many infringements made on this precious freedom elsewhere.⁶⁰

And it should be noted that the teachers of the College have never been threatened in their quest for truth or in uttering it as they understand it during the nearly twenty-five years of operation.

In his closing remarks at the alumni dinner in 1956, the speaker urged MJC to become during the next ten years a real cultural and vocational center for the county.

This means that the College will have to operate virtually around the calendar. There must be other additional educational and recreational offerings beside the symphony orchestra and chorus. Summer school must become a regular part of the college program. The possibility of a reading clinic ought to be given serious consideration. Such a clinic would not only take care of the reading problems of our own students but those of school children in the county.⁶¹

As it turned out, practically all of these suggestions were realized during the following decade. In the fall of 1956, Marlin Hill joined the faculty as a remedial reading instructor. Heretofore, remedial reading had been handled in English 9, Fundamentals of Reading and Vocabulary, a non-transfer course.⁶² Since 1959, the College has regularly conducted an eight-week summer session, in which students have been allowed to take no more than two courses. During the past five years there has been a host of educational and recreational offerings for the community at large on both the Takoma Park and Rockville campuses.

The college year 1956–57 began on the theme “A Decade of Progress” and closed with the commencement address of Dr. Raymond S. Stites of the National Gallery of Art, “Where Do We Go From Here?” The enrollment had increased by more than 150 over the preceding year, and there were fifteen additional teachers, eight full-time and seven part-time. (See Appendices A & B.)

The next five years, 1956–61, saw a considerable expansion of enrollment, faculty, programs, and extracurricular activities at MJC. Moreover, it is worth noting that four new community colleges in Maryland opened in the fall of 1957, bringing the total then to eleven: Catonsville and Essex in Baltimore County, Harford, and Frederick.⁶³

One of the areas in which expansion was reflected at MJC was the establishment of four extension centers in the spring semester of 1959. Courses in secretarial studies, English, public speaking, mathematics, and sociology were to be given at North Bethesda Junior High School, and Bethesda Chevy Chase, Richard Montgomery and Wheaton High Schools. A year later additional courses in mathematics, English, economics, sociology, history, political science, and social science were offered at Richard Montgomery, Wheaton and Northwood High Schools. “In 1962 the importance of the evening and extension programs was recognized with the establishment of a new office, that of Dean of Evening and Extension Courses and Institutional Research.”⁶⁴

When the College began its fifteenth year of operation in the fall of 1960, two new curricula had been added: Dental Assisting and Electronic Data Processing, now referred to as Computer Science and Technology.

MJC was one of six colleges in the United States which were to take part in a five-year experimental program on Dental Assisting sponsored by the Division of Dental Public Health and Resources of the U.S. Public Health Service. At the termination of the experiment, the curriculum was to continue as one of MJC’s regular courses. The program itself led to an A.A. degree and its work included clinical experience and training arranged in conjunction with the Georgetown University School of Dentistry. Electronic Data Processing, the other new entry in MJC’s curricula field, was added in recognition of the rapid growth in business and research of computers and their auxiliary equipment, particularly in the Washington-Metropolitan area. Concentrating on research and development electronic data processing, the curriculum prepared the graduate to assist professionals in project planning, problem formulation, system design, programming, production and such related services as maintenance, and the operation of EDP library facilities.⁶⁵

A year after the Dental Assisting and Electronic Data Processing curricula were established, a pilot program in Radiation Technology developed in close cooperation with the U.S. Public Health Service was launched. The new curriculum was designed to prepare graduates for positions in which ionizing radiation was used. Upon graduation from the program the student could be employed as a radiation health technician. Moreover, if the graduate so desired, he could work towards an advanced degree in biochemistry, biophysics, or radiobiology. Three years after the Radiation Technology curriculum was established, the Atomic Energy Commission granted a special nuclear materials license to MJC. “In addition, the Nuclear Chicago Corporation awarded the College an educational grant to permit the purchase of a dual-channel gamma-ray spectrometer system at an approximate saving of $5,000.”⁶⁶

Meanwhile, in 1959–60, the College’s Medical Technology curriculum, which originated in 1947, was aligned with a corresponding program at The American University in Washington, D.C. The curriculum as revised was designed to prepare students for more advanced work at American University. As a consequence, MJC became the first two-year college in the United States to dovetail its medical technology curriculum with that of a four-year institution, it having done so on the recommendation of the American Association of Clinical Pathology and with the endorsement of the American Medical Association. In 1969, a summer institute in Radiation Biology for secondary school teachers was sponsored jointly by The American University and the College as a result in part of the efforts of Dr. Evelyn M. Hurlburt, Professor of Biology and Radiation Science at the Takoma Park campus.

During the late fifties and early sixties, several new student organizations appeared on campus. With the opening of the 1957–58 college year, the Key Club was established as a service organization, the requirement for membership having been that a student had to belong to at least one other campus club or activity. Two years later, the Circle K Club superceded the Key Club. The Silver Spring Kiwanis Club acted as the sponsoring body for Circle K, and Mr. Charles McCalla of the Chemistry Department served as the faculty adviser until his death in 1964.

The Social Philosophy Club, under the sponsorship of Dr. Wallace W. Culver, was yet another student activity which made its appearance in the late fifties. With Dr. Culver’s enthusiastic support, this organization provided programs dealing with various social and political issues and frequently invited outside speakers to discuss topics of current interest.

In the spring of 1960 the College received the charter for Kappa Omega Chapter of Phi Theta Kappa, the national junior college honorary society. Members were to have at least a “B” average, to carry regularly a schedule of at least fifteen semester hours, to be in the upper ten percent of the regularly enrolled student body, and, moreover, to be of good moral character. Through the efforts of Mr. Stephen G. Wright, the first faculty sponsor, the Phi Theta Kappa chapter became a reality after a delay of several years due to some faculty opposition.

It was also in the spring of 1960 that Scuderia, a club dedicated to the love and knowledge of sports cars, was organized with the stimulating support of its faculty adviser, the late Everett “Jake” Jacoby. A popular organization, Scuderia sponsored rallies in which the participants demonstrated their driving skills on a prescribed course under timed conditions.

† † †

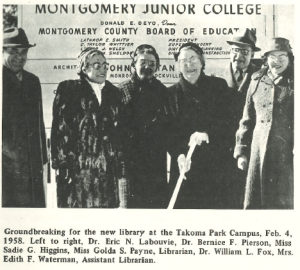

In October, 1957, the Montgomery County Board of Education approved an appropriation of $150,000 for a new library which was to have a capacity of 25,000 volumes. Since 1950 when the College moved on to the Takoma Park campus, the library had been housed in the least fire-resistant of the six buildings! And the College had outgrown its limited size and accommodations. The plans for the new library, which was to have a seating capacity of 175 in the reading room, included open stacks, offices, work room, audio-visual room, listening rooms, and a faculty conference room and lounge. On February 4, 1958, ground was broken for the College’s first newly constructed building. The school superintendent, mayor of Takoma Park, and the president of the Board of Education took part in the ground breaking ceremony. Eight months later the building was completed, the formal opening date having been set for December 3. To accomplish the move from the old to the new library, students formed a chain whereby books were quickly passed from one person to another. As the Accolade noted, “the new library [was] the first physical sign of the growing pains of our expanding school.”⁶⁷ An attractive building in many respects, it fell short of what Miss Golda Payne, the Librarian, had recommended after visiting several college libraries and studying carefully the literature on the subject. She felt that it would be much better to have the new library built on one floor rather than, as it turned out, on two. In order to reduce the problems of noise and cleaning, Miss Payne suggested carpeting the floors.⁶⁸ Instead, they were tiled.

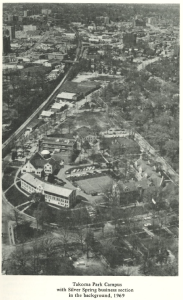

Not only had the administration and faculty recommended for the immediate future a new library but a science building, a gymnasium-field house, and additional parking facilities.⁶⁹ In 1958 the Board of Education approved preliminary plans for a science building which was to include biology, chemistry, and physics laboratories on separate floors, as well as offices, a 210-seat lecture hall, a smaller lecture hall which would seat about 70, and possibly a small planetarium which ultimately was incorporated in the building plans on the advice of Dr. Everett Hurlburt, a physicist and amateur astronomer and husband of a member of the College’s science faculty.⁷⁰ The new science building, which opened in September of 1960, was erected on the site of the old library, members of the science faculty having meanwhile spent much time with Dean Deyo and the architect in drawing up and later reviewing floor plans. While it is probably true that the science building came closer to faculty expectations than had the library, there were a few disappointments, one of them being the location of the green house. The biology instructors wanted it on the roof of the main part of the building. Instead, it was placed on the roof of the lecture hall, just off the bacteriology laboratory! Since the opening of the science building in 1960, there has been no further construction on the Takoma Park campus. However, plans are presently being made for the redevelopment of that campus.

A few months before the science building opened, Burling H. Lowrey of the English Department published a book on Twentieth Century Parody: American and British (New York, 1960), which contained such parodical delights as Robert Benchley’s “Compiling An American Tragedy” (Suggestions as to How Theodore Dreiser Might Write His Next Human Document and Save Five Years’ Work), Donald Ogden Stewart’s “The Courtship of Miles Standish” (In the Manner of F. Scott Fitzgerald), and B.A.Y.’s “Inside John Gunther.” Although a few other members of the faculty published articles and books in the fifties and early sixties, they and their colleagues in general were not particularly encouraged to do so. College faculties in general and MJC in particular have not been research and publication oriented, except for internal institutional studies, the philosophy being that the major function of such institutions is teaching. Furthermore, the relatively heavy teaching loads of the full-time faculty has tended to discourage writing and research.

Probably no event in 1960 was more important than the adoption of the report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Committees by a unanimous vote of the faculty late in April. At a faculty workshop which was held the previous September, attention was devoted in part to the College’s committee system, which needed overhauling. The faculty was divided into small study groups, each of which examined carefully this issue and in turn presented a report to the whole faculty on September 11. About a week and a half later Dean Deyo appointed the chairmen of these study groups to serve as an ad hoc committee to review the various group reports and to make recommendations for the revision of the institution’s committee system. The members of this important committee included Mrs. Margaret Aldrich, Jack W. Henry, Jr., who served as chairman, Dr. Eileen P. Kuhns, Lionel Nelson, and Irvin H. Schick.

The ad hoc committee presented its report to the faculty on November 13, 1959. After an extensive discussion of this report during the next several months by members of the faculty and administration, a motion to accept and implement the committee’s report was passed by a unanimous vote of the faculty on April 28, 1960. For the first time in the College’s history, therefore, a faculty senate — designated as The College Policies Committee — became an integral part of the College’s organizational structure during the academic year 1960–61.⁷¹

The function of the College Policies Committee was “…to act as agent for the entire faculty in the formulation of policy in all matters pertaining to the College and its work.”⁷² The C.P.C.’s authority did not go beyond the formulation and recommendation of policy; and the Ad Hoc Committee on Committees, from the start, accepted without equivocation that premise. However, Dean Deyo, when he first saw the Ad Hoc Committee’s report, felt that the power granted to the C.P.C. was an infringement upon his authority. So the report had to be revised in order to make doubly sure that such was not the case.⁷³

A voting membership of the C.P.C. included the Dean of the College (or his appointed representative), one additional ex-officio member to be appointed by the Dean, who turned out to be the Assistant Dean, Lee L. Ehrbright, and eight full-time members of the faculty. The chairman of the committee was chosen by all ten members. Provision was made for two separate elections of the faculty representatives. In one election representatives were selected from each of four major areas: humanities; social science and business administration; library, physical education, and student personnel; and mathematics, science, and technology. In the other election, four additional faculty members were elected to serve as representatives-at-large. These elections were held during the spring faculty workshops, the term of office having been set at two years except that in the first election the four representatives-at-large were to serve for only one year.

The first faculty representatives elected to C.P.C. in the spring of 1960 were: Jack W. Henry, Jr., who subsequently became chairman, Louis G. Chacos, Harvey J. Cheston, Emery Fast, Dr. William L. Fox, Allen H. Jones, Dr. Bernice F. Pierson, and Dr. Alice J. Thurston.

Generally the C.P.C. met regularly as a committee of the whole. In turn this body was divided into sub-committees on Appointments and Tenure, Grievances, and Organization, which met less frequently. The new system called for eight standing committees of the faculty which were responsible to C.P.C.: Academic Regulations, Academic Status, Athletic Board of Control, Curriculum, Library and Audio-Visual Education, Student Personnel Services, Student Activities, and Activities of the Academic Community. Several old committees such as those concerned with admissions, educational policy, and public relations had been eliminated by the introduction of the new system.

Undoubtedly the two most important accomplishments of C.P.C. during its first year of operation were the complete departmentalization of the College and the introduction of a system of professorial rank. Other than the English and Electrical Technology (the name of the latter had meanwhile been modified) Departments, there were no others when the C.P.C. began to function. By the fall of 1960, there were on campus 1500 students and a faculty of 113. With such growth departmentalization was necessary for both the administration and the faculty. The Sub-Committee on Organizations composed of Lee Ehrbright, Jack Henry, and the author, who served as chairman, drew up a plan providing for the establishment of sixteen departments. Late in March 1961, Dean Deyo announced to the faculty his approval of the departmental organization as recommended by C.P.C. and the names of the faculty whom he had appointed as department chairmen: Economics and Business Administration, Stephen G. Wright; Biology, Dr. Bernice F. Pierson; Chemistry, James T. W. Ross; Engineering and Technology, Irvin H. Schick; English (including speech and philosophy) Allen H. Jones; Modern Languages, Dr. Eric N. Labouvie; History and Political Science, Dr. William L. Fox; Mathematics, Harvey J. Cheston; Physical Education, Louis G. Chacos; Secretariat Training, Mrs. Virginia G. Pinney; Sociology, Dr. Wallace W. Culver; Fine Arts, Mrs. Mildred M. Nichols; Orientation and Psychology, Dr. Alice J. Thurston; Dental Assisting, Mrs. Jane C. Frost, whose actual title was Director; and Library, the late Mrs. Edith F. Waterman, Head Librarian.⁷⁴

At a meeting of the College Policies Committee on March 8, 1961, a proposed system of academic rank was adopted, the proposal having been prepared by an ad hoc committee headed by Dr. Wallace Culver. Each full-time member of the faculty, according to the proposal, was to be assigned the title of instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, or professor, “the particular assignment of ranking depending upon: 1. Length of tenure at the College, 2. Prior teaching experience, 3. Academic training and degrees.”⁷⁵ The categories of academic rank were established on the basis of years of service: instructor, 0–7 years; assistant professor, 8–12 years; associate professor, 13–17 years; and professor, 18 years or more. A master’s degree or its equivalent was equal to two years of service, and thirty semester hours of credit beyond the master’s degree was to be considered the equivalent of three years of service. Possession of the doctorate was equated with four years of service. To be considered for the rank of associate professor, the faculty member had to achieve tenure and for the rank of professor, Career Recognition, a system of self-evaluation which Dr. C. Tayler Whittier, the Superintendent, with the approval of the Board of Education, inaugurated in the spring of 1959, as a means of increasing teachers’ salaries and of bringing to the attention of the individual teacher the need for periodic evaluation of his performance. (Career Recognition was neither popular with the elementary and secondary school teachers in the county nor with the MJC faculty during the four years it was in operation.) Although the proposal for academic rank was clearly not related to salaries or to increments on the salary schedule — the administration and a probable majority of the faculty would not have supported it — the Board of Education was unwilling to accept the recommendation until provision was made for evaluation of teachers, both in the classroom and in related professional activities. The C.P.C., in turn, incorporated such a provision in the proposal which the Board then approved. The assignment of and promotion in rank, based on evaluation, now became the responsibility of the department chairmen, the Sub-Committee on Appointments and Tenure, and the administration.

By June 1961, the College, not only had a system of professorial rank, something which the Middle States Report of 1950 had suggested, but a system of sixteen functioning departments whose chairmen were responsible for making budgetary recommendations, interviewing and recommending candidates for teaching positions, ordering of supplies and equipment, and preparing annual reports. These developments were indeed symptomatic of the growth of the College as were the construction of the Library and Science Building.

Certainly another symptom of MJC’s expanding enrollment was the proposal of a second campus in the Rockville area, which had been first discussed at a faculty meeting in April 1956.⁷⁶ The growth of the county’s population and MJC’s student body caused the superintendent of schools to predict in December 1960, a need for five junior colleges in Montgomery County.⁷⁷ “There was no question but what there were widely varying opinions on how and where to expand MJC. It was proving far easier to talk about expansion than to implement the idea.”⁷⁸ Three months after Dr. Whittier made his prediction the Board purchased a site for the second campus.

In March 1961, the Board of Education bought, with the approval of the State Superintendent of Schools, 87 acres of land off Route 355 just beyond the western limits of Rockville, having received assurance that the tract would be annexed to the city and that water would be brought to it.⁷⁹ Delighted with the location of MJC’s second campus, the mayor and council of Rockville announced in December 1962, the annexation of the new college site, effective January 12, 1963.⁸⁰

Meanwhile, Dean Deyo urged the various departments to commence to make plans for the Rockville Campus by, among other things, discussing with consultants the plan and design of their respective areas.⁸¹ Many hours were spent by the departments and department chairmen in working up the needed recommendations for the new campus. By June 1962, the recommendations of Odell MacConnell and Associates, educational consultants of Palo Alto, California, were presented to the faculty. These included: a TV studio and control room, a science-mathematics center, twelve biology laboratories with 1,500 square feet of greenhouses, eight chemistry laboratories, one laboratory for work on isotopes, three laboratories for physics, a psychology laboratory, and a 60-seat planetarium. The Odell MacConnell consultants also recommended a fine arts center which would house a little theater, a drama laboratory, and a dance studio. Two pools for physical education were also included in the report.

However, it was not until September 26, 1963, that the site work, including the clearing and putting in of roads, was begun; and the building construction did not get under way until mid-May of 1964, almost three years after the Board of Education had purchased the tract of land. Meanwhile, there had been elected to the Board in November 1962, on an “economy” platform, Charles W. Bell, William E. Coyle, William I. Saunders, and Everett H. Woodward. They outvoted the three encumbents and prevented the appropriation of funds for construction until they had an opportunity to study the junior college program. A study group comprising the seven Board members was formed to review the College’s program after which the Board was able in May to approve an appropriation of $3.5 million for the Rockville Campus, there having been vigorous protests against the suspension of the building program by various groups and individuals, including the Student Government President, Robert Maddox.⁸² The Board set a tentative opening date for September 1965, and decided that it would be best in the meantime to limit the acceptance of out-of-state applications for admission. Moreover, the Board, by a vote of 4 to 3, proposed closing the Takoma Park Campus when the Rockville Campus was able to take care of the entire needs of the county. “Public opinion, though, indicated there was still much discussion to be heard on the threat to eliminate the original campus.”⁸³ The coup de grace to the plan for closing the Takoma Park Campus came when Dr. Thomas G. Pullen, Jr., the State Superintendent of Schools, refused a request for state matching funds amounting to several hundred thousand dollars for a technical-vocational building and a fourth floor to the humanities building. Funds were available to expand or improve the original campus but, momentarily, not for the new! The Board had to reconsider its position concerning the closing of the Takoma Park Campus. As a result, the state superintendent approved a grant of $512,750 which matched an appropriation by Montgomery County, for the technical building on the Rockville Campus.

Besides the technical building, the new campus was to include a library, a fine arts building, a student center and cafeteria, a science building, a gymnasium, a student personnel and administration building, and a humanities building. By September 1965, the Rockville Campus was ready for occupancy. With its opening a new chapter in the history of the College and of Maryland community colleges was to begin. At present there are six additional buildings under construction, making for a total of 13 which will accommodate 5,000 full-time and 3,000 part-time students when the last of the new construction is completed by December 1971.⁸⁴

† † †

While the plans for and construction of the Rockville Campus absorbed much of the institution’s collective attention and energy in the early 1960’s, several interesting as well as significant developments were taking place at the Takoma Park Campus. In the fall of 1961, the Modern Foreign Languages Department began operation of a language laboratory, completely equipped with listening carrels and a master console. Greater emphasis could thus be given to the oral-aural approach to the study of French, German, Spanish, and Russian.

A year later, the College initiated for superior high school seniors an “early placement” program, which was to supplement their high school offerings with college-level courses. The students had to be in the upper 20 percent of their classes and be recommended by the high school counselors. Those who were thus selected could take either freshman or sophomore level courses and receive college credit. Except for books and transportation, the county bore the entire expense of this program which the students seemed to enjoy.⁸⁵

For the exceptionally able college students, MJC established in 1963 the Honors Program which came to include such courses as the Great Depression and the Era of Reform, 1929-41, Concepts of Science, and Mathematics and Western Culture. Today there are a dozen courses offered in this program on the two campuses, a recognition that the College is not only interested in the weak or poorly prepared student but in the superior as well.

During the summer of 1963, under the direction of Dr. Eileen P. Kuhns who was then Assistant Dean for Institutional Research and the Evening, Extension and Summer School Division, MJC made a survey of the needs of metropolitan employers in the following categories: medical auxiliary technologies, business, applied science technologies, and public service. “Respondents participating in the 1963 Survey numbered 551 firms, employing a total of 153,886 employees, who in turn constituted about one-fifth of the 1960 total work force resident in the metropolitan Washington area.”⁸⁶ Although the original objective for the Survey was to identify occupational programs which might be offered at the Rockville Campus, the research resulted “in a broadened conception of this purpose.”⁸⁷

It was also in 1963 that Dean Deyo was elected president of American Association of Junior Colleges at its annual meeting, having served for the past year as vice president. Some years before, he had been president of the Maryland Association of Junior Colleges.

In the fall of 1963 the Student-Faculty Disciplinary Board was established to deal with non-academic behavior. It was composed of four students and three members of the faculty. Although a student court had been established about six years before, it never met as there were no violations ever reported.⁸⁸ The new Student-Faculty Disciplinary Board during its first year of operation heard cases involving a total of 19 students, nine of whom were acquitted. Dean Deyo concurred with all the Board’s recommendations.⁸⁹ This joint student-faculty board, in which students held a majority of the seats, was created, it should be noted, a few years before campus unrest swept the country.

By the time the Disciplinary Board had been established, the office of Dean of Instruction had been in effect for two years. This position was filled by Dr. George B. Erbstein who had come to the College as Assistant Dean for the Evening and Extension Division. Subsequently he helped to institute such two-year programs as computer science, nursing, and radiation technology. Later, his title changed from Dean of Instruction to Dean of Faculty, a position which he held until the spring of 1967 when he became president of Ulster County Community College, Stone Ridge, New York.

In the summer of 1964, at the urging of the Board of Education, the College set up a special summer program for students who had graduated in the lowest quartile of their class. The purpose of the Basic Studies Program, which the University of Maryland had previously inaugurated, was to enable the students to qualify, upon successful completion of two courses (a non-credit review course in English and one giving credit, e.g., American Government), for admission to the College in the fall. This program, which was conducted for four years, replaced entering-on-probation for students in the lowest quartile of their high school graduating class. The previous provision had stipulated that students could not take more than fourteen semester hours during their first semester, could not participate in more than one extra-curricular activity, and would have to achieve at least a 1.50 average (C-/D+) their first semester if they wished to remain in college. Neither the Basic Studies Program nor the earlier entering-on-probation requirement is now in effect, although there is remedial work in English, mathematics, and reading offered on a voluntary basis. Consequently the College, with regard to the weak, poorly prepared student, is now faced with a situation analogous to what it confronted during the first half dozen years of its operation.

† † †

During commencement week, 1964, it was learned that one of the students who was about to graduate had arranged for her sister to sit in one of her classes of the past semester so that she could achieve a better than passing grade, the student in question having previously failed the course. Strong disagreement with the administration arose from the faculty and the College Policies Committee when the student was allowed to graduate. “Though the School Board rescinded the degree, the damage was done and Dean Deyo chose to accept another appointment.⁹⁰ In February, 1965, after nearly twelve years as the Dean of the College, Mr. Deyo left to become Director of the Master-Study Plan of the Massachusetts Board for Regional Community Colleges. “My twelve years at MJC,” observed Deyo in his closing remarks, “have never ceased to be challenging and exciting. The College still has this potential.”⁹¹ And he added:

In the fall of 1953 we registered just under 400 students; in the fall of 1964, we registered over 2,800. The growth in enrollment has been accompanied by growth in all aspects of the College program: faculty, curriculum, student activities. Students should feel privileged to attend MJC. It has an outstanding national reputation as one of the top community colleges of America.⁹²

Opinions concerning Dean Deyo’s professional ability, as one might expect, varied among members of the college community. Some found him to be approachable, earnest, efficient, and conscientious. To others, Dean Deyo had “a managerial approach to running the College.”⁹³ And the tendency to regard members of the faculty as “employees” rather than as professional people trained in academic disciplines. “Any appraisal of Deyo as an administrator,” Emery Fast, Professor of Political Science, thoughtfully observes, “must take into account the fact that the ‘aura of poverty’ that surrounded the College during his administration was due to his and Dean Ehrbright’s determination to show the taxpayers of the county that junior college education was not prohibitively expensive.”⁹⁴ Nevertheless, during Dean Deyo’s tenure at the College, the enrollment increased, the faculty was enlarged, new curriculums appeared, faculty governance was established, and a second campus was planned and under construction.

With his departure Lee L. Ehrbright again became Acting Dean of the College, as he had been in the summer of 1953. Meanwhile, Ehrbright had arranged to teach at El Camino College in California on an exchange the following year. In turn, Dr. Edgar F. Love was to teach political science at the newly opened Rockville Campus.

† † †

The major interest at the College in the spring of 1965 was the selection of a successor to Dean Deyo. Upon the recommendation of the College Policies Committee, the Board of Trustees (Board of Education) invited the faculty to participate with the administration in the selection of a president (the new title for the chief administrator). As a result, members of CPC and department chairmen had the opportunity to meet the several candidates and to make recommendations. Having approved the faculty’s recommendation, the Board then announced the appointment of Dr. George A. Hodson, Jr., President of Skagit Valley College, Mount Vernon, Washington. A native of Minnesota, the new president, who was then 49 years of age, was a graduate from Mankato State College, had earned a second bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington and an M.A. from Columbia University, and the year before he came to MJC had obtained the Ed.D. degree from Washington State University. Although Dr. Hodson had only two years of teaching experience beyond the secondary level, he had served for thirteen years as president of Skagit Valley College.

Besides the concern for the selection of the president, the Board also considered in May 1965, the question of liberalizing the admission requirements for out-of-county residents. Both Acting Dean Ehrbright and Dr. Whittier, the Superintendent, favored this proposal which “would have admitted out-of-county and out-of-state high school graduates ranking in the upper three-fourths on the ACT entrance examination, instead of just those in the upper half of their graduating class.”⁹⁵ With the new campus, it was felt that there would be no problem of space and that a greater diversity of the student population would be desirable. The Board, however, by a vote of four to two, declined to accept the recommendation.

With the appointment of a new president and the expectation of opening the new campus in September, the summer of 1965 was a time of excitement, hope, and rumor at the College. Fifteen years before, MJC had made ready to occupy a “new campus” as it was now about to open a new, second campus at Rockville. To be sure, a decade and a half is not a long time in the history of human institutions; yet the fifteen years between 1950 and 1965 had seen this institution grow from an unknown little junior college of 540 students to a two-campus community college of 3700 students and a faculty of nearly 280, a truly remarkable chapter in the history of higher education in the State of Maryland.

Footnotes:

- Takoma Park: A Photo History of Its People by Its People, 75 Years of Community Living 1883–1958, 1958, p. 5.

- Ibid., pp. 5–6.

- Knights’ Quest, 11 Oct. 1950.

- Harold S. Wood, personal interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 10 Feb. 1970.

- Bliss School of Electricity, Announcement for 1896–97, p. 5. From 1899 on, the institution was identified as The Bliss Electrical School.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Knights’ Quest, 11 Oct. 1950.

- Ibid., 1 Dec. 1950.

- Golda S. Payne, personal interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 7 Oct. 1969.

- Harold S. Wood, personal interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 10 Feb. 1970.

- “Montgomery Junior College Survey-Planning Conference August 17-18, 1950” (ditto copy), MJC-Conference with Consultants (Aug. 17, 18, 1950) Folder, Montgomery College Records.

- “Resume of Montgomery Junior College Survey-Planning Conference, August 17-18, 1950” (typewritten copy), Folder cited in Footnote 11.

- Catalog, 1954-55, pp. 28-29.

- See Footnote 12.

- Henry W. Littlefield, Bridgeport, Conn., letter, 1 Sept. 1950, to Hugh G. Price, Montgomery College Records.

- James R. Mock, Professor of Sociology, telephone interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 11 July 1970.

- Knights’ Quest, 11 Oct. 1950.

- Ibid., 7 Nov. 1950.

- Dr. Ralph E. Himstead, then General Secretary of the American Association of University Professors and a former professor of law at Syracuse University, agreed completely that the suspension of the instructor was an act of prejudgment and granted permission to be quoted on this matter. Ralph E. Himstead, telephone interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., n.d., 1950.

- “Meeting of the Montgomery Junior College Chapter of the American Association of University Professors – October 19, 1950” (stenographic report prepared by Harriett Preble Ripley), files of the author.

- Knights’ Quest, 17 Jan. 1951.

- Price, “Five-Year Report of the Dean, 1946–1951,” p. 1. See Footnote 30 in previous chapter.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 9

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Fox, “The First Ten Years and After — At Montgomery Junior College.”

- Harold S. Wood, personal interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., 10 Feb. 1950.

- Lander, p. 58.

- Knights’ Quest, 23 April 1953.

- In the summer of 1951, Dean Price was invited to teach a course on the junior college at the University of Maryland.

- Freda Malone, Professor emeritus of English, Silver Spring, Md., memorandum, n.d., 1970, to the author.

- Stephen G. Wright, Professor of Business Administration and Economics, Takoma Park, Md., memorandum, 12 Feb. 1970, to the author.

- George S. Morrison, Professor of Chemistry, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Ariz., letter, 31 Jan. 1970, to the author. It was Dr. Morrison who successfully completed the codification of the College’s academic regulations before Dean Price left and who introduced the numbering system which has since been followed in the regulations.

- F. Frank Rubini, Associate Director of Parks, The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Silver Spring, Md., letter, 30 Jan. 1970, to the author.

- Fretwell, op. cit., p. 87.

- A Report of the Faculty on Policy Recommendations Prepared by the Montgomery Junior College Faculty and Unanimously Adopted June 12, 1953 (mimeographed), Montgomery College Records.

- Ibid.

- Lander, p. 47.

- Ibid. Faculty Minutes, 15 March 1954, Montgomery College Records.

- J. Parker Bogue, the son of Dr. Bogue, formerly a member of the faculty of Odessa College, Texas, personal interview with the author, Takoma Park, Md., n.d.

- Sadie G. Higgins, former Director of Student Personnel, now Professor emeritus, Minneapolis, Minn., letter, n.d., 1970, to the author.

- William L. Fox, Takoma Park, Md., letter, 12 April 1954, to Bernice F. Pierson. Dr. Pierson served that year as an exchange professor at San Bernardino Valley Jr. College, San Bernardino, California.

- James O. Harmon, Silver Spring, Md., letter, 22 Jan. 1970, to the author.

- Morrison. See Footnote 38 in this chapter.

- Donald E. Deyo, Franklin, Mass., letter, 7 Nov. 1969, to the author.

- Catalog, 1954–55, p. 37.

- Report of the Evaluation Committee of the Commission on Institutions of Higher Education of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools. (Montgomery Junior College, Takoma Park, Maryland, March 6–8, 1955.) Montgomery College Records.

- Fox, “The First Ten Years and After — At Montgomery Junior College.”

- Middle States Report, 1955.

- Report of the Committee to Study the Junior Colleges, Rockville, Md., March 1, 1955, 53 pp., Montgomery College Records.

- Ibid., p. 49.

- Ibid., p. 50.